Imagine a world where the same animal could be a beloved family member in one home and the centerpiece of a dinner table in another. This isn’t just a cultural oddity—it’s a global reality. Every day, millions shower their dogs with affection, while millions of pigs are slaughtered for food. Yet both animals are intelligent, sentient, and capable of forming deep bonds with humans. Why do we draw such stark lines of compassion? The answer lies deep within our brains, shaped by evolution, culture, and the mysterious workings of our emotions. Understanding this paradox is more than just an academic exercise—it shakes us to our core and forces us to question the very foundation of empathy.

The Roots of Selective Compassion

Selective compassion isn’t simply a matter of personal taste; it’s a complex psychological phenomenon with ancient roots. Humans have always needed to decide which animals to befriend and which to fear or consume. Early societies made these choices based on survival—some animals were easier to tame, others provided essential resources. Over generations, these practical decisions became ingrained cultural norms, shaping emotional responses and even neural wiring. Today, we might not question why we adore dogs while eating pigs, but beneath the surface, our brains are hardwired by centuries of habit and necessity. This selective empathy helps us navigate a world full of moral ambiguities, offering comfort, but also creating blind spots.

How Culture Shapes Our Empathy

Culture acts as a powerful lens that colors our perception of animals. In some countries, cows are sacred and untouchable, while in others, they’re a staple food. Dogs in Western societies are family, loyal companions who sleep at the foot of our beds. Meanwhile, in other parts of the world, dogs may be seen as working animals or even food. These attitudes are not innate—they are taught from birth, reinforced through stories, rituals, and social expectations. The brain’s mirror neurons, which allow us to empathize, are trained by these cultural cues, determining which creatures we see as worthy of care. Cultural norms are so powerful that they can override even our most basic instincts of kindness.

The Brain’s Emotional Shortcuts

Our brains are built to take shortcuts when processing emotional information. The amygdala, a small almond-shaped region deep within the brain, plays a big role in how we feel about animals. When we see a dog’s wagging tail or soulful eyes, the amygdala fires up, releasing feel-good chemicals that foster attachment. With pigs, unless we’ve had personal experiences, our brains remain emotionally neutral or even detached. This difference isn’t about the animals themselves—it’s about the mental associations we’ve built over time. The brain defaults to compassion for animals we see as “in-group,” while easily ignoring the suffering of those we label as “other.” This shortcut saves mental energy but can create huge ethical gaps.

The Power of Familiarity and Attachment

Attachment forms the heart of our relationships with animals. Dogs have lived alongside humans for thousands of years, evolving alongside us and learning to communicate in ways that tug at our heartstrings. Their loyalty, expressive faces, and playful antics make it easy for us to feel a deep connection. Pigs, on the other hand, are rarely kept as companions. Because we don’t see their personalities up close, it’s easier for our brains to keep them at a distance. Familiarity breeds affection, and the lack of it breeds indifference. This stark difference is less about the animals’ qualities and more about our own exposure and experience.

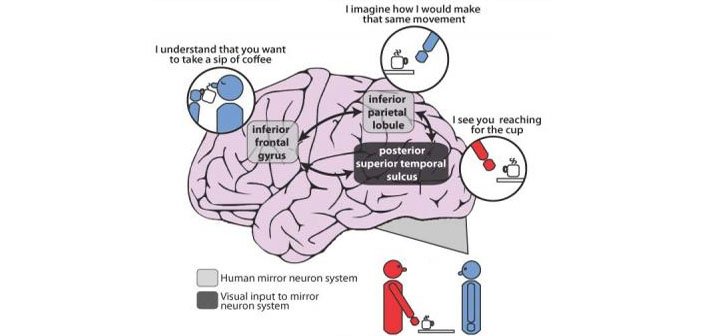

Mirror Neurons and Empathy in Action

Mirror neurons are special brain cells that let us feel what others feel. When a dog jumps with joy, our brains light up in response, creating a shared moment of emotion. These neurons help us relate to people and animals alike, but their effects depend on the stories we tell ourselves. If we see pigs only as food, our mirror neurons stay silent. But when people meet pigs at animal sanctuaries, something amazing happens: the barriers fall, empathy floods in, and perceptions shift. This shows just how powerful—and changeable—our neural wiring can be.

The Role of Language and Labels

Words have a profound influence on our emotions. We call cows “beef,” pigs “pork,” and chickens “poultry,” stripping away the animal’s identity and making it easier to eat them without guilt. In contrast, we call our dogs by names—Max, Bella, or Daisy—emphasizing their individuality. These labels shape our neural responses, dampening empathy for animals labeled as food and enhancing it for those labeled as companions. This linguistic divide is not accidental; it’s a psychological buffer, protecting us from uncomfortable feelings and making selective compassion possible.

Media, Marketing, and Social Influence

The images and stories we see every day reinforce our emotional boundaries. Advertisements show happy dogs and cats, never pigs or cows. Children’s books are filled with heroic pets but seldom feature farm animals as friends. These subtle cues train our brains from a young age, influencing which animals we see as lovable and which we see as products. Social media amplifies these messages, spreading cultural attitudes at lightning speed. The result is a world where compassion is channeled and controlled, often without our conscious awareness.

Scientific Insights into Animal Intelligence

Research has shattered the myth that only certain animals are intelligent or capable of emotion. Studies have shown that pigs are as clever as dogs, capable of playing video games, solving puzzles, and forming strong social bonds. Yet this knowledge often sits alongside our habitual behaviors without changing them. Our brains can hold contradictory beliefs, allowing us to recognize an animal’s intelligence while still participating in systems that harm them. This cognitive dissonance is a testament to the brain’s incredible flexibility—and its capacity for self-deception.

Cognitive Dissonance: Living with Contradiction

Cognitive dissonance is the psychological discomfort we feel when our actions clash with our values. Many people love animals and oppose suffering, yet still eat meat. To resolve this tension, the brain invents justifications: “Pigs are different,” “It’s natural,” or “It’s what everyone does.” These mental tricks soothe our conscience but keep the cycle of selective compassion turning. Overcoming cognitive dissonance requires confronting uncomfortable truths, a process that is never easy but often transformative.

Hope for a More Compassionate Future

Neuroscience reveals that empathy is both powerful and pliable. As we learn more about animal consciousness, emotional intelligence, and our own psychological biases, the boundaries of compassion begin to shift. Stories of people who befriend pigs, rescue cows, or adopt turkeys show that change is possible. With each new connection, our brains adapt, expanding the circle of care. The journey toward a more inclusive empathy is slow, but every step counts. What would our world look like if we let empathy guide us, rather than habit or tradition?