Beneath the icy waters of the Antarctic, scientists have uncovered a chilling new threat lurking in the deep. Parasitic creatures, dubbed “undersea vampires,” have been found feeding on the flesh of unsuspecting fish.

The Horrifying Discovery Beneath Antarctic Waters

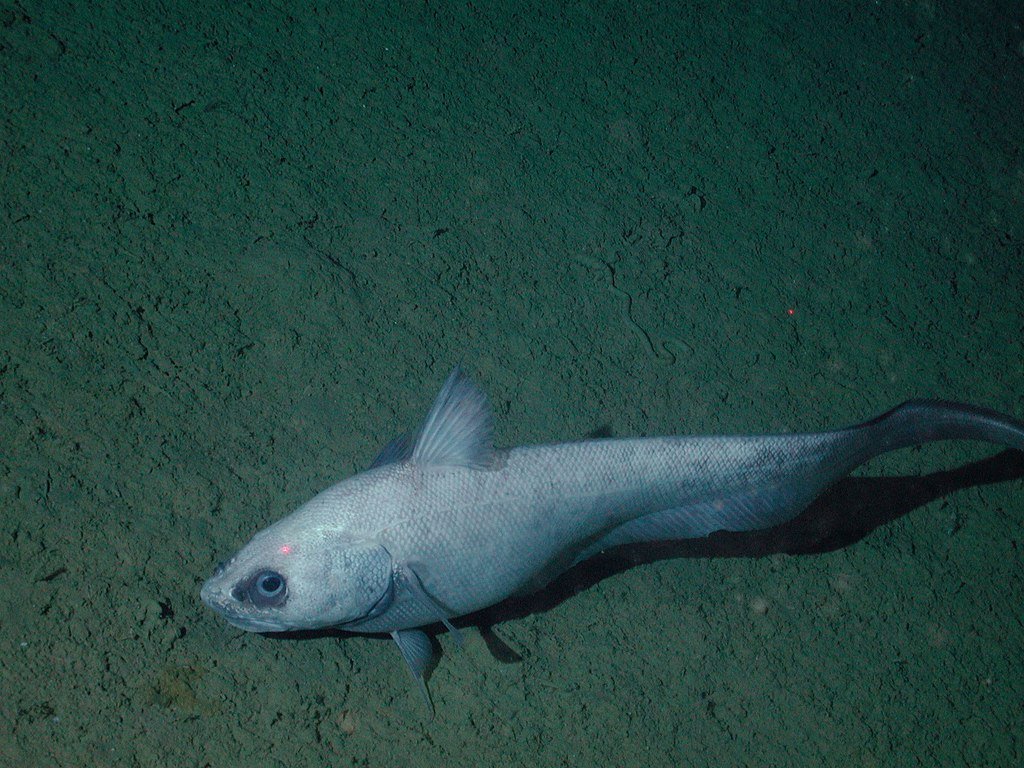

In a discovery that seems ripped right out of a sci-fi horror flick, scientists investigating the ocean floor near the South Sandwich Islands have filmed some unsettling scenes parasites firmly attached to the heads of deep-sea fish.The parasites copepods from the species Lophoura szidati were seen embedded in a rattail fish (Macrourus genus), their egg sacs dangling like grotesque pigtails. The footage, released by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, offers a rare look at the eerie, brutal relationships that define life in Earth’s most extreme environments.

The parasitic copepods are not merely passengers. They are mesoparasites, meaning they burrow into the muscle tissue of their host, feeding on blood and bodily fluids while their bodies hang outside. As if conjured from a Lovecraftian nightmare, these creatures carry egg sacs that appear almost ornamental until you learn they’re teeming with hundreds of larvae, awaiting their turn in the life cycle of aquatic vampirism.

Copepods: Bloodsucking Crustaceans in Disguise

Whereas copepods are normally innocuous planktonic drifters within marine ecosystems, the Lophoura szidati species is anything but. The parasitic crustaceans burrow into fish flesh with their razor-sharp mouthparts. Having established themselves, they suck up nutrients directly from muscle tissue, essentially becoming part of the host body.

According to evolutionary biologist James Bernot of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, these parasites are capable of embedding their head-end into the host fish while their body including reproductive organs remains outside. Even after death, remnants of the copepod’s head can remain inside the host for years, a chilling testament to their deeply invasive existence.

The Rattail Fish: A Host With No Escape

The unfortunate host in the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s video is a rattail fish, also known as a grenadier. These deep-sea fish inhabit depths ranging from 1,312 to 10,450 feet across the North and South Atlantic and the Southern Ocean. With their large heads and whip-like tails, they are well-adapted to life in frigid, dark waters but not to the relentless assault of parasitic invaders.

The copepods on either side of the fish head are symmetrically attached in the video. All this and dangling sacs impart the impression as if the fish has pigtails, a dreadfully humorous one covering up its actual horror in being in its situation.

Life Cycle of a Deep-Sea Vampire

Copepod parasites such as Lophoura szidati undergo a multi-stage life cycle that starts from microscopic larvae. These larvae infect their host’s skin and transform, developing holdfast structures for anchoring permanently. Females, as they grow, form external egg sacs that harbor hundreds of eggs until they become nauplius larvae and future parasites in the process.

Despite their grotesque existence, copepods are considered unusually attentive mothers among invertebrates. They carry their offspring externally, ensuring a high survival rate. However, much about their lifespan remains unknown. Some researchers believe these parasites can live for several months while embedded in the host, a hauntingly long sentence for any fish unlucky enough to encounter one.

The Pigbutt Worm: Another Monster From the Deep

This discovery joins a long list of bizarre marine revelations, including the infamous “pigbutt worm.” First discovered in 2001 off the coast of California by researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, this translucent, pink blob was jokingly named for its resemblance to a pig’s posterior. Scientifically referred to as Chaetopterus pugaporcinus, the animal is not easily categorizable.

Although at first rejected as larval bristle worms, their puffed up body and peculiar size 10 to 20 times bigger than larvae bewildered researchers. When examined under the microscope, they seemed to maintain juvenile characteristics long into adulthood, a condition referred to as neoteny. Despite decades of research, their biology is still not understood.

What Lies Beneath: The Unknown Depths of Marine Parasitism

Antarctic and sub-Antarctic ocean depths are among the most uncharted places on this planet. There are over 90% more deep-sea species that still need to be described, state marine biologists. Every journey is yielding surprises, sometimes magical, sometimes grim.

The South Sandwich Islands mission is a prime example of the dual nature of deep-sea exploration: the discovery of new life and struggling with the ugly beauty of evolutionary survival. From blood-sucking copepods to cheeky pigbutt worms, these organisms make us reconsider the laws of biology and how far life will stretch to live.

Why These Discoveries Matter

And even though parasitic copepods and pigbutt worms sound like a horror movie, they’re necessary components of ocean life. Parasitism, odd as it is, is a significant force in evolution. By learning about these ocean vampires, scientists are not only gaining insight into the resilience of life in extreme conditions but also learning about the evolutionary arms race between predator and prey.

It’s important to understand these ocean dynamics because climate change and human activities are compromising even the farthest reaches of our oceans. Every bizarre creature is a piece of the bigger puzzle of biodiversity, one scientists are in a mad dash to finish before time runs out.

Sources

- Live Science – Scientists capture footage of bizarre deep-sea creature with parasite pig tails

- National Geographic – Pigbutt Worm: Ocean Mystery

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.