Deep in the Amazon rainforests, on remote Pacific islands, and within impenetrable mountain ranges, some of humanity’s most remarkable communities continue to live as they have for thousands of years. These isolated tribes represent fewer than 200 groups worldwide, with estimates pointing to roughly 10,000 individuals total maintaining their traditional ways of life without sustained contact with modern civilization.

Recent estimates suggest approximately 100-200 uncontacted peoples living across various countries, with the majority residing in South America, particularly Brazil which harbors 124 groups. Yet these guardians of ancient wisdom face unprecedented threats as you’ll discover. From the arrow-wielding Sentinelese to the club-carrying Korubu, let’s explore nine extraordinary tribes that continue to resist the modern world while preserving cultural treasures that could disappear forever.

The Sentinelese: Earth’s Most Isolated People

Among the world’s more than 100 uncontacted tribes, the Sentinelese stand as the most isolated Indigenous people on Earth. Living on North Sentinel Island, a landmass roughly the size of Manhattan in the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago about 500-600 miles from the Indian mainland, visiting their island is prohibited by Indian law to maintain their way of life and protect them from modern illnesses. They are thought to be directly descended from the first human populations to emerge from Africa, and have probably lived in the Andaman Islands for up to 55,000 years.

The Sentinelese hunt in the rainforest and fish in coastal waters using spears, bows and arrows, as well as homemade narrow outrigger canoes, and are thought to live in three groups in both large communal huts and more informal shelters on the beach. Except for a brief, friendly interaction in the early 1990s, they have fiercely resisted contact with outsiders, even after disaster – in 2004, following the Asian tsunami, a member of the tribe was photographed firing arrows at a helicopter sent to check on their welfare.

The Yanomami: Amazonian Warriors of Venezuela and Brazil

The Yanomami are the largest relatively isolated tribe in South America, living in the rainforests and mountains of northern Brazil and southern Venezuela, with their territory in Brazil spanning over 9.6 million hectares, twice the size of Switzerland. For centuries, they have inhabited a vast area of pristine forest and large, meandering rivers on the border between Brazil and Venezuela, living off fishing, hunting and fruit gathering, with today’s population numbering about 29,000.

Like most Amazonian tribes, tasks are divided between the sexes – men hunt for game like peccary, tapir, deer and monkey, often using curare to poison their prey, though hunting accounts for only 10% of Yanomami food while women tend gardens growing around 60 crops which account for about 80% of their food. Their ancestral territory faces invasion from illegal prospectors seeking gold and valuable minerals who have cut down forests, poisoned rivers with mercury, and brought deadly diseases to the tribe.

The Korubu: Club-Wielding Guardians of the Javari Valley

The Korubu, also known as the Dslala, are a largely uncontacted, Panoan-speaking indigenous people of Brazil living in the lower Vale do Javari in the western Amazon Basin, calling themselves ‘Dslala’ and referred to in Portuguese as caceteiros (clubbers). They are one of seven uncontacted tribes living in the Javari Valley on the border of Brazil and Peru, with seven contacted tribes also present, making the region home to one of the highest concentrations of isolated people on the continent.

Their hunting weapon of choice is the club, aside from poison darts they use no other ranged weapons, with their workday being about 4-5 hours long, often living inside large, communal huts known as malocas, while both men and women paint themselves with red dye from the roucou plant and hunt spider monkeys, peccary, birds and wild pig. Despite FUNAI’s efforts, the main tribe continues in complete isolation with population figures estimated from aerial reconnaissance to be a few hundred individuals, while a smaller contacted band has frequent interaction with neighboring settlements.

The Mashco Piro: Peru’s Emerging Forest Dwellers

Survival International documented about 53 male Mashco Piro appearing on riverbanks in Peru in 2024, with the group estimating as many as 100 to 150 tribal members would have been in the area with women and children nearby. Photos emerged in July 2024 of the uncontacted tribe searching for food on a beach in the Peruvian Amazon, with members gathering on the banks of Las Piedras river where they have been sighted coming out of the rainforest more frequently.

Loggers were killed after entering Mashco Piro territory in Peru’s Amazon, with Indigenous leaders warning that such clashes are inevitable when frontier zones go unpoliced, as Peru’s government had recognized in 2016 that the Mashco Piro and other isolated tribes were using territories that had been opened to logging. In previous conflicts, two loggers were shot with arrows while fishing in 2022, one fatally, in an encounter with tribal members.

The Awá: Brazil’s Most Endangered Forest Nomads

The Awá are one of the last remaining semi-nomadic tribes in Brazil, residing in the Maranhão state of the Amazon rainforest, and are among the most endangered Indigenous groups with a very small population that needs to defend their territory from several external threats, most prominently deforestation. Illegal logging, deforestation, and other encroachment have made the Awa among the most vulnerable uncontacted tribes on Earth, with only about 60-80 of the roughly 600 remaining Awa still living nomadic, uncontacted lives.

The Awá rely on the rainforest’s natural resources for their survival, hunting, fishing, and gathering, using two-metre-long spears and utilising their extensive knowledge of forest resources. Their deep connection to the Amazon rainforest that has sustained them for millennia now hangs by a thread as external pressures mount.

The Jarawa: Ancient Islanders of the Andaman Sea

The Jarawas are believed to be descendants of the Jangil tribe and it is estimated that they have been in the Andaman Islands for over two millennia, along with other indigenous Andamanese peoples who have inhabited the islands for several thousand years. The Jarawa people are a Paleolithic tribe consisting of only 200 to 450 individuals living in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of the Indian Ocean, with diseases such as recent measles outbreaks drastically reducing the population.

As a nomadic tribe, they hunt endemic wild pigs, monitor lizards and other quarry with bows and arrows, with men fishing with bows and arrows in shallow water while mollusks, dugongs and turtles form a major part of their diet. The construction of the Great Andaman Trunk Road passes directly through their forested settlements, introducing new migrants and enabling “human safaris” where foreigners observe indigenous populations like zoo specimens.

The Ayoreo: Paraguay’s Last Voluntary Isolationists

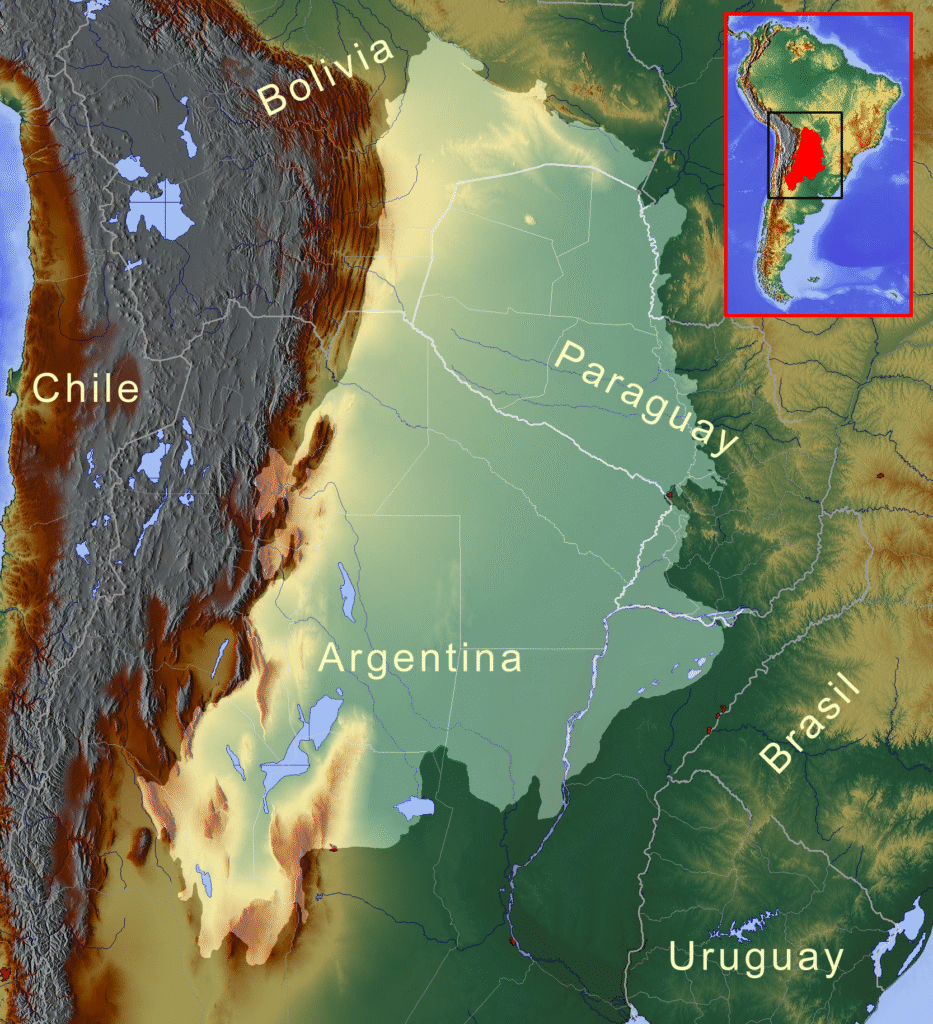

The Ayoreo reside in the Gran Chaco region spanning across parts of Paraguay and Bolivia, with much of the group retaining their semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, relying on the forest for survival, and being among the last Indigenous groups living in voluntary isolation in South America. They hunt wild game, gather fruit and honey and rely on vegetation for medicine, while some sub-groups such as the Totoiegosode – known as the ‘people of the wild pigs’ – choose to avoid all contact with the outside world out of fear that their ways of life will be disrupted.

Ayoreo’s land has been increasingly threatened by deforestation driven by cattle ranching and land clearance, as Gran Chaco is one of the most rapidly disappearing forests in the world, with these activities forcing some Ayoreo out of their forest homes, exposing them to disease and forcing integration into modern society.

The Shompen: Great Nicobar’s Endangered Hunter-Gatherers

The Shompen or Shom Pen are the Indigenous people of the interior of Great Nicobar Island, part of the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, with the population estimated at approximately 300 in 2001, practicing a hunter-gatherer subsistence economy. Survival International says that the Shompen are one of the most isolated peoples on earth, with most of them being uncontacted and refusing interactions with outsiders.

Due to the proposed Great Nicobar Development Plan, hectares of land will be reclaimed to build a “Hong Kong India” with an airport, international port, and industrial park, which may impact 1,700 people including many Shompens, with 39 genocide experts from 13 countries warning in February 2024 that the development “will be a death sentence for the Shompen, tantamount to the international crime of genocide”.

The Hongana Manyawa: Indonesia’s Mining-Threatened Forest People

Survival International’s report points to the uncontacted Hongana Manyawa on Indonesia’s Halmahera Island, where nickel for electric-vehicle batteries is being mined. A 2024 report claimed that their forest was being destroyed by the nickel mining industry. Indonesia is home to many uncontacted tribes, with most centered in Western New Guinea, though even groups that have chosen to remain isolated have run into mining activity that threatens their way of life, and Indonesia has no specific protections for isolated indigenous groups.

The irony is stark – as the world races toward electric vehicles to combat climate change, the very materials needed for this green revolution threaten to destroy one of Earth’s last uncontacted peoples. Their traditional knowledge of sustainable forest management could offer invaluable insights for environmental conservation, yet industrial pressures continue to encroach on their ancestral lands.

Conclusion

These isolated Indigenous tribes are “at the edge of survival” as growing contact by missionaries, miners, criminal gangs and social media influencers spreads diseases and wipes out forests, with at least 196 such groups remaining, half of whom could be wiped out in under a decade. Each tribe carries irreplaceable knowledge about sustainable living, traditional medicine, and environmental stewardship that humanity desperately needs in our climate crisis.

Isolated indigenous societies who actively avoid sustained peaceful contact with the outside world are critically endangered, with last year marking another cultural extinction event as “Tanaru,” the lone surviving man of his tribe for at least 35 years, died in Southwest Amazonia. Yet these resilient communities have survived for millennia and deserve our protection, not our interference. Their choice to remain isolated should be respected as we learn from their remarkable ability to live in harmony with nature for thousands of years.

What do you think about our responsibility to protect these last guardians of ancient wisdom? Tell us in the comments.