If you still picture memory as a dusty filing cabinet in your brain, science is about to blow that image apart. Over the last few years, researchers have discovered that memory is less like a static archive and more like a living, constantly edited Google doc that your brain keeps rewriting. Some of the most basic things we thought we knew – like where memories live, how long they last, and whether lost memories are really gone – are being turned inside out.

This matters in a very real way. It changes how we think about trauma, dementia, learning, even our own identities. I still remember reading one of these studies late at night and feeling a weird chill: if my memories can be edited, how much of my story is solid, and how much is a flexible script? Let’s walk through eight breakthroughs that are reshaping what “remembering” actually means – and what that might mean for you.

1. Memory Is Not a Single Thing – It’s a Whole Ecosystem

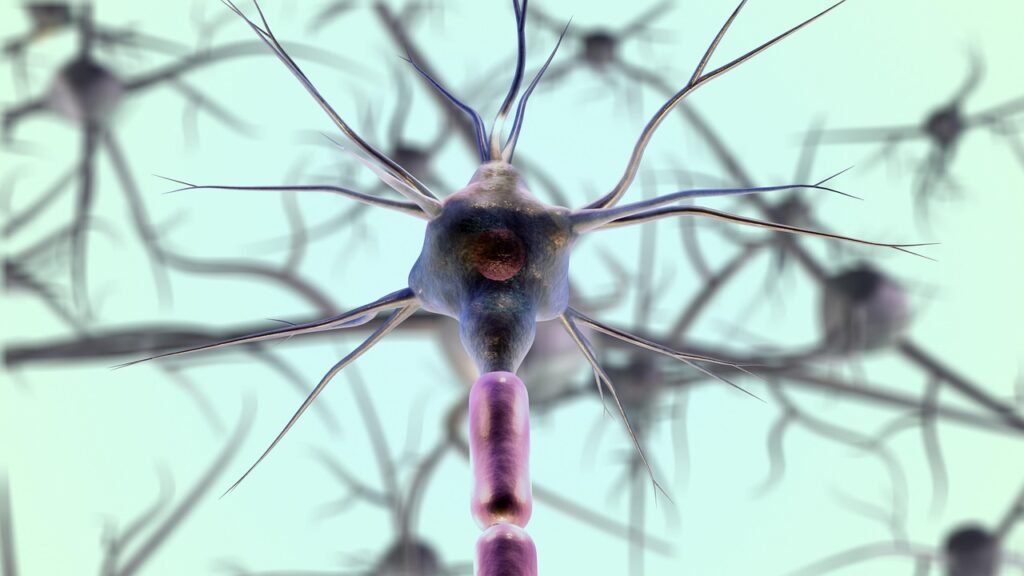

For a long time, psychology textbooks treated memory as a few neat categories: short-term, long-term, maybe working memory if the book was modern. New brain imaging and computational models now show that memory is more like an ecosystem with overlapping networks, each specializing in different aspects of experience. Instead of one central “memory center,” there are distributed circuits for emotional tone, spatial context, sensory details, and meaning, all talking to each other.

This has led scientists to rethink what it even means to “store” a memory. The current view is that a memory isn’t a single stored object, but a pattern of activity that can be reconstructed from many pieces. It’s like remembering a vacation: your brain doesn’t pull out a single folder; it reassembles the weather, the smell of the sea, the feeling in your chest, the hotel layout, your friend’s voice. That reconstruction process can vary slightly each time, which helps explain why memories shift subtly over years without us noticing.

2. The Brain Keeps Editing Memories Every Time You Recall Them

One of the most unsettling discoveries of the last two decades, now backed by stronger evidence, is that remembering is a form of rewriting. When you recall a memory, it becomes temporarily unstable, a process called reconsolidation. During this window, which can last minutes to hours, the memory trace can be strengthened, weakened, or altered before being stored again. In other words, every time you replay the story, you’re also editing it.

Recent experiments with both animals and humans have shown that carefully timed interventions during this reconsolidation window can reduce the emotional punch of painful memories. For example, exposure-based therapies for phobias and trauma now try to deliberately trigger and then update the memory with new, safe information. It’s not about erasing what happened, but about loosening the grip of the old emotional script. The flip side is more uncomfortable: telling a dramatic story over and over can make it more vivid and more distorted, even if your intent is to be accurate.

3. Memories Can Be Artificially Activated – and Even “Written”

In the last several years, neuroscientists using techniques like optogenetics in animals have identified and manipulated specific groups of neurons that encode particular memories, often called engrams. They’ve been able to activate a fear memory in a mouse just by switching on the neurons linked to that memory, even when the animal is in a totally safe environment. That’s like flipping a light switch and triggering a wave of panic, with no external reason.

Even more striking are experiments where researchers tagged neurons active during a neutral experience and later paired the activation of those neurons with something aversive, like a mild foot shock. The result: the animal behaved as if the original neutral context was dangerous, as though a new fear memory had been “written” onto a previously harmless scene. While this work is still far from human application, it supports the idea that memories are not mystical; they’re physical patterns that, in principle, can be turned on, off, or remixed.

4. Sleep Isn’t Just Rest – It’s a Memory Editing Studio

Sleep research has gone from “sleep helps memory” to “sleep is doing highly specific memory operations” – and the details are surprising. During deep sleep, especially slow-wave sleep, the brain appears to replay recent experiences in compressed bursts of activity, particularly between the hippocampus and the cortex. This replay helps stabilize important memories while quietly discarding a lot of irrelevant clutter. It’s like your brain running a nightly highlights reel and deciding what’s worth keeping.

Studies have even shown that subtle cues during sleep, such as faint sounds linked to a learning task, can bias which memories are replayed and strengthened. At the same time, other research suggests that sleep can soften the emotional intensity of painful experiences while preserving the facts. That might be why after a really bad day, you often feel just a tiny bit more distant from it the next morning. In that sense, your bed is not just where you crash; it’s where last day’s raw footage gets edited into tomorrow’s story.

5. The Immune System and the Gut Are Quietly Shaping Memory

One of the biggest plot twists comes from outside the brain: memory is not purely a neural story. Evidence now shows that immune cells and inflammatory molecules can significantly influence how well we learn and remember. Chronic inflammation, whether from illness, stress, or lifestyle, can interfere with the formation of new memories and accelerate cognitive decline. On the flip side, some immune signaling appears necessary for healthy memory formation, so it’s not as simple as “inflammation is bad.”

Layered on top of that, research on the gut–brain axis has linked the composition of gut microbes to performance on memory tasks in both animals and humans. Changes in the microbiome can alter the production of neurotransmitter-related substances, affect stress hormones, and tweak immune responses that feed back to the brain. It’s wild to think that what’s happening in your intestines can shape how clearly you remember a conversation or a childhood event. Memory, it turns out, is not just in your head; it’s a full-body phenomenon.

6. Emotional Memories Are Wired Differently – and More Stubbornly

We’ve always known that intense emotional experiences tend to stick, but modern brain imaging and molecular studies are explaining why. Emotional memories often recruit the amygdala, a region deeply involved in detecting threat and significance, which then boosts encoding in the hippocampus and related areas. That partnership lays down stronger, more resilient traces, especially for experiences colored by fear, shame, or joy. It’s like the brain quietly flagging certain moments as “do not forget under any circumstances.”

What’s new is the nuance: emotional memory is not just stronger; it can also be more selective and biased. People tend to remember the emotional gist more than the exact details, which can distort recollections over time. Studies of trauma and anxiety show that people may recall danger cues more easily than safety signals, which can feed into persistent vigilance or avoidance. This helps explain why some memories feel like they are burned into your mind, while others around them fade, leaving a story that is emotionally true but factually patchy.

7. Digital Life Is Changing How, Not Just What, We Remember

Memory science is now colliding with the reality of smartphones, cloud storage, and constant notifications. Researchers are finding that outsourcing information – like relying on search engines and photo archives – can change the way we encode experiences in the first place. When we know something is easily retrievable online, we tend to remember how to find it rather than the content itself. It’s less of a library in our heads and more of a map to external libraries.

At the same time, the nonstop stream of digital distractions competes with the deep, undivided attention that complex memories require to form. There’s emerging evidence that heavy multitasking is linked to shallower encoding and more fragmented recollection, like skimming ten tabs instead of reading one book. On the flip side, digital tools can support memory for people with cognitive challenges, acting as external scaffolding. The big shift is this: memory is no longer just biological; it’s becoming braided together with our devices and apps in a way previous generations never had to navigate.

8. Memory Loss May Be More About Access Than Destruction

For decades, conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias were framed mostly as the irreversible death of neurons and loss of stored information. While cell loss is still a big piece, new work suggests that in some cases, memories may persist in damaged networks but become inaccessible. Animal studies have shown that when researchers artificially stimulated specific memory engrams in models of early-stage memory impairment, the animals could retrieve information they otherwise seemed to have forgotten. It’s like discovering that the files are still on the hard drive, but the operating system can’t find them.

This shift in thinking has inspired approaches that focus on rescuing or stabilizing access to existing traces instead of assuming they are gone forever. Treatments targeting synaptic function, metabolic support for neurons, and network-level rhythms are all being explored with this in mind. It doesn’t mean a simple cure is around the corner, and it would be dishonest to pretend otherwise, but it does open a more hopeful angle: in some forms of memory loss, the goal might be to rebuild the search engine, not recreate the entire library from scratch.

There’s something strangely comforting in knowing that you are not just a prisoner of your past; your brain is always rewriting, reweighting, reframing. At the same time, it’s a little disorienting to realize just how malleable your most personal stories really are. Maybe the most practical takeaway is this: the way you sleep, manage stress, pay attention, and retell your experiences is already sculpting tomorrow’s memories. Knowing that, what will you choose to remember more clearly – and what might you gently let fade?