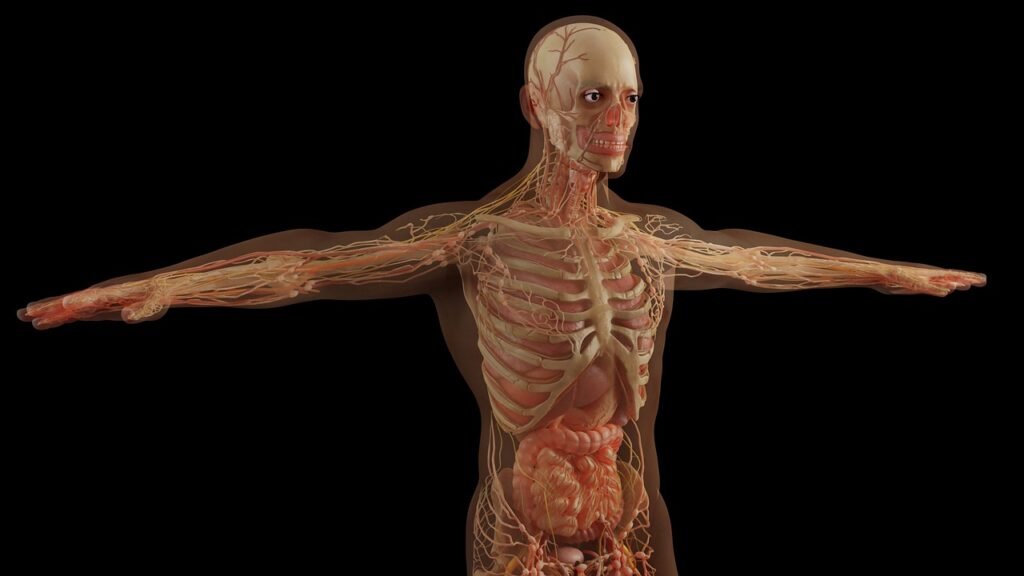

If you’ve ever been told that human evolution “basically stopped” once we invented agriculture or smartphones, you’ve been sold a comforting myth. Evolution never clocks out. It’s not a chapter that ended; it’s the invisible edit button still quietly rewriting our bodies generation after generation, right in the middle of the story.

What’s wild is that a lot of these changes aren’t unfolding in some distant future. They’re happening now, in living people, sometimes within the span of a few generations. From how we digest food to how we grow bones, our species is still tinkering with itself in response to modern life, strange diets, crowded cities, and new diseases. Some of these changes are subtle, some are surprisingly fast – and together, they’re proof that we’re far from a finished product.

1. Extra Arm Arteries: The Middle Arm Vessel Making a Comeback

Imagine going in for a medical scan and finding out you have an “extra” blood vessel running down your arm that most anatomy textbooks still treat as rare or temporary. That vessel, called the median artery, usually forms in the womb but used to disappear before birth in most people. Over the last century or so, though, researchers have found that more and more adults are keeping it for life, like a body “feature” that quietly refused to be phased out.

Some studies comparing bodies from past centuries with modern ones suggest that roughly about one third of people today retain this artery into adulthood, far more than in earlier generations. For surgeons, it can be either a bonus blood supply or an unexpected complication, but from an evolutionary point of view, it looks like a trait that’s becoming more common over time. No one can say with total certainty why, but one reasonable guess is that having that extra artery might slightly improve blood flow or resilience in the forearm and hand. If it offers even a small advantage, natural selection can nudge it along, one generation at a time.

2. Lactose Tolerance: Turning a Baby Trait into a Lifetime Upgrade

For most mammals, milk is strictly a baby food. When they grow up, the gene activity that allows them to digest lactose, the sugar in milk, basically switches off. Humans started the same way, but in populations that domesticated cows, goats, or sheep, something radical happened: a genetic change allowed some adults to keep producing lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose. That meant they could drink milk without getting bloated, crampy, or sick – a serious survival edge in places where dairy was a reliable food source.

What’s striking is just how fast this spread in certain regions. In parts of Europe, East Africa, and the Middle East, lactase persistence shot up in a relatively short evolutionary window once milk became part of the daily menu. Today, some populations have the vast majority of adults who can digest lactose easily, while others, especially in East Asia and parts of West Africa and South America, still have many people who are lactose intolerant. Evolution here is not about “better” or “worse” humans, but about different genetic solutions to different food environments – and those pressures only arose a few thousand years ago, which is basically yesterday in evolutionary time.

3. Wisdom Teeth: The Disappearing Set of Trouble-Makers

If you’ve suffered through wisdom tooth surgery, you’ve probably wondered why on earth our bodies still grow teeth that often don’t fit in our mouths. The short answer: they made more sense when our ancestors had bigger jaws and chewed tougher, raw food that wore teeth down. Today, with soft, cooked, and processed diets, our jaws tend to grow smaller, while that old genetic program for extra molars hasn’t completely caught up. The result is a lot of crowded smiles and dental appointments.

But there are clues that evolution is slowly hitting the delete key. In some populations, a noticeable share of people are born without one or more wisdom teeth, and this toothless trend seems to be increasing. Jaw size and tooth number are influenced by both genes and environment, but if having fewer or no wisdom teeth reduces pain, infections, and surgical risk, that can translate into a subtle evolutionary push. Over long timescales, our descendants may look back and see wisdom teeth as a strange, half-phased-out relic from when our diets demanded stronger jaws instead of straighter smiles.

4. Changing Heights and Body Shapes: Adapting to Food, Climate, and Cities

Walk through any big city and you’ll see it: humans come in an incredible range of heights and builds, and that diversity isn’t random. Over human history, body size and shape have shifted in response to climate, nutrition, disease, and lifestyle. Taller, leaner bodies tend to lose heat more easily and have historically been more common in warmer regions, while shorter, stockier builds help conserve heat and have appeared more often in colder environments. These patterns are not perfect, but they echo a deep evolutionary logic.

In the last century or so, improved nutrition and healthcare have pushed average heights up in many countries, especially where chronic childhood malnutrition used to be common. At the same time, modern sedentary lifestyles and calorie-dense diets have driven up rates of obesity almost worldwide, which complicates the picture. Some of what we see is pure environment, but some traits, like how and where we store fat or how quickly we burn energy, have genetic components that evolution can act on. As city living, shift work, and ultra-processed food become the backdrop for life, our bodies are being tested in new ways that could shape future generations’ builds and metabolisms.

5. Disease Resistance and the Ongoing Genetic Arms Race

Every time a new infectious disease spreads, it becomes a brutal, real-time test of our immune systems. Historically, outbreaks like smallpox, plague, cholera, malaria, and influenza left their fingerprints in our DNA. People whose genes helped them survive passed those genes on, and over many generations, certain variants became more common. For example, some genetic changes that help protect against malaria are more frequent in regions where mosquitoes and malaria have been long-term threats.

We’re still in that arms race today, even if antibiotics, vaccines, and hospitals change the rules. Modern pandemics, recurring viral outbreaks, and even the way we crowd into mega-cities all shape which immune-related genes matter most. At the same time, medicine can keep people alive who might not have survived in the past, which slightly shifts how natural selection works. Evolution doesn’t stop just because we invented intensive care units; it just has to navigate a more complex landscape where pathogens, treatments, and human genes are constantly interacting and adjusting to each other.

6. Brains, Stress, and the Cognitive Demands of Modern Life

Our brains haven’t suddenly tripled in size over the last few centuries, but the mental environment we live in has changed dramatically. We’re constantly flooded with symbols, screens, languages, and decisions in a way our ancestors never were. Education has become the norm in many places, not a luxury, and that means generations of people are growing up in homes and schools that push memory, attention, and complex problem-solving from an early age. The brain is incredibly plastic, so much of this is about experience – but there’s room for genetics to play a role in who thrives in this kind of mental pressure cooker.

On the flip side, chronic stress, anxiety, and sleep disruption are now part of everyday life for a lot of people, especially in dense urban environments. Our stress response systems evolved for short bursts of danger, not endless deadlines, notifications, and financial worry. Some researchers suspect that genetic variants affecting mood, resilience, and how we handle stress may be under new evolutionary pressures as societies change. I’ve felt that personally: the difference between a week of good sleep and a week of late-night screen scrolling is like switching between two entirely different brains, and that’s a small glimpse into the delicate balance our nervous systems are trying to maintain in a world they weren’t designed for.

7. Evolving Digestion and Microbiomes in a Processed Food World

For most of human history, our guts were tuned to diets full of fiber, roughage, and natural variation – wild grains, roots, fruits, and whatever else the landscape offered. Now, a lot of people live on ultra-processed foods, refined sugars, and industrial oils. That shift hasn’t just changed our waistlines; it’s reshaping the complex communities of microbes living in our intestines. Those microbes help digest food, train our immune system, and even influence mood, and they’re heavily molded by what we eat, where we live, and how we’re born.

Some people seem better adapted than others to modern diets, at least in terms of blood sugar response, weight gain, or gut comfort, and part of that comes down to genes interacting with the microbiome. There are already known genetic differences in how we process things like starch, alcohol, and fats across populations with different food histories. Now we’re layering in artificial sweeteners, preservatives, and highly engineered snacks, effectively giving evolution a new set of puzzles to solve. Our descendants may inherit digestive systems and microbial ecosystems subtly tuned to handle a world of packaged food in ways our bodies are still struggling with today.

A Species in Motion, Not a Finished Design

Human evolution isn’t a museum exhibit frozen behind glass; it’s more like a construction site that never shuts down, even if the work is too slow and subtle to notice day to day. Extra arm arteries, shifting tooth patterns, changing heights, evolving disease resistance, new stress responses, and gut adaptations are all separate threads in the same story: our bodies are still responding to the pressures of the world we’ve built for ourselves. Some changes play out over thousands of years, others noticeably speed up when a new food source, disease, or lifestyle suddenly matters for survival or reproduction.

What makes this moment unusual is that we’re both the product and the driver of those pressures, with technology, medicine, and culture all feeding back into biology. We’re editing our environments, and in the long run, those environments will edit us right back. Instead of asking whether humans are still evolving, a better question might be: which of today’s habits and challenges will leave the deepest marks on the humans who come after us, and which of these shifts did you least expect?