They ruled shorelines, forests, and ancient skies with bone-thick legs and wings that cast noon-dark shadows. Then, almost as quickly as a page turns, they were gone. Scientists are piecing together their disappearances from scorched eggshells, fossil wind-borne wings, and DNA whispers preserved in desert caves. The mystery isn’t just how these giants lived, but why size – once a winning strategy – turned into a fatal bet. As new tools sharpen the picture, each extinct bird carries a warning for our era of rapid change.

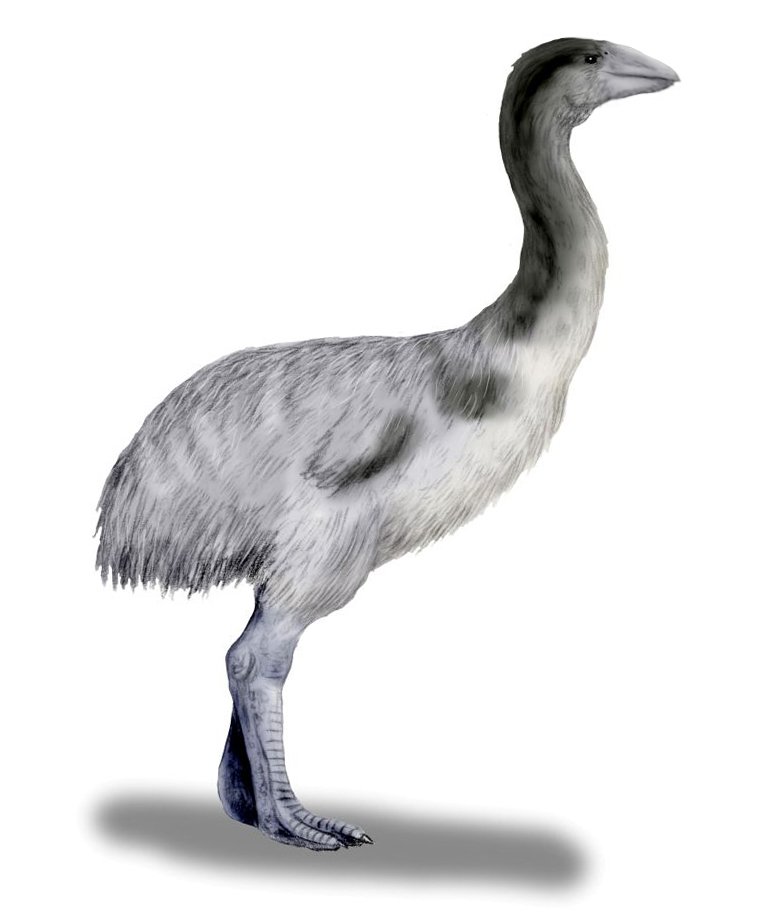

Elephant Birds of Madagascar: The Heaviest Birds That Ever Lived

Elephant Birds of Madagascar: The Heaviest Birds That Ever Lived (image credits: wikimedia)

Imagine an egg large enough to fill two restaurant mixing bowls – elephant bird eggs could hold the volume of roughly about one hundred and fifty chicken eggs. These flightless titans, including species like Aepyornis and the newly recognized Vorombe, were ground-shaking herbivores that roamed Madagascar’s forests into the last millennium. Their bulk made them nearly untouchable, yet also tethered them to slow reproduction and fragile habitats. Archaeological sites scattered with eggshell fragments suggest people collected their eggs, while burning and grazing reshaped the landscape. In a slow-motion collapse, low birth rates couldn’t keep pace with human pressure.

Scientists now see a convergence of stressors rather than a single catastrophic blow. Drought cycles squeezed food supplies in patchy forests, and even limited hunting or egg gathering could tip a population that replaced itself at a glacial pace. Island endemics with no predators often lack defenses, and elephant birds were textbook examples. As forests thinned, these giants had nowhere to retreat and no time to adapt. The last echoes likely faded between the late medieval period and early modern centuries.

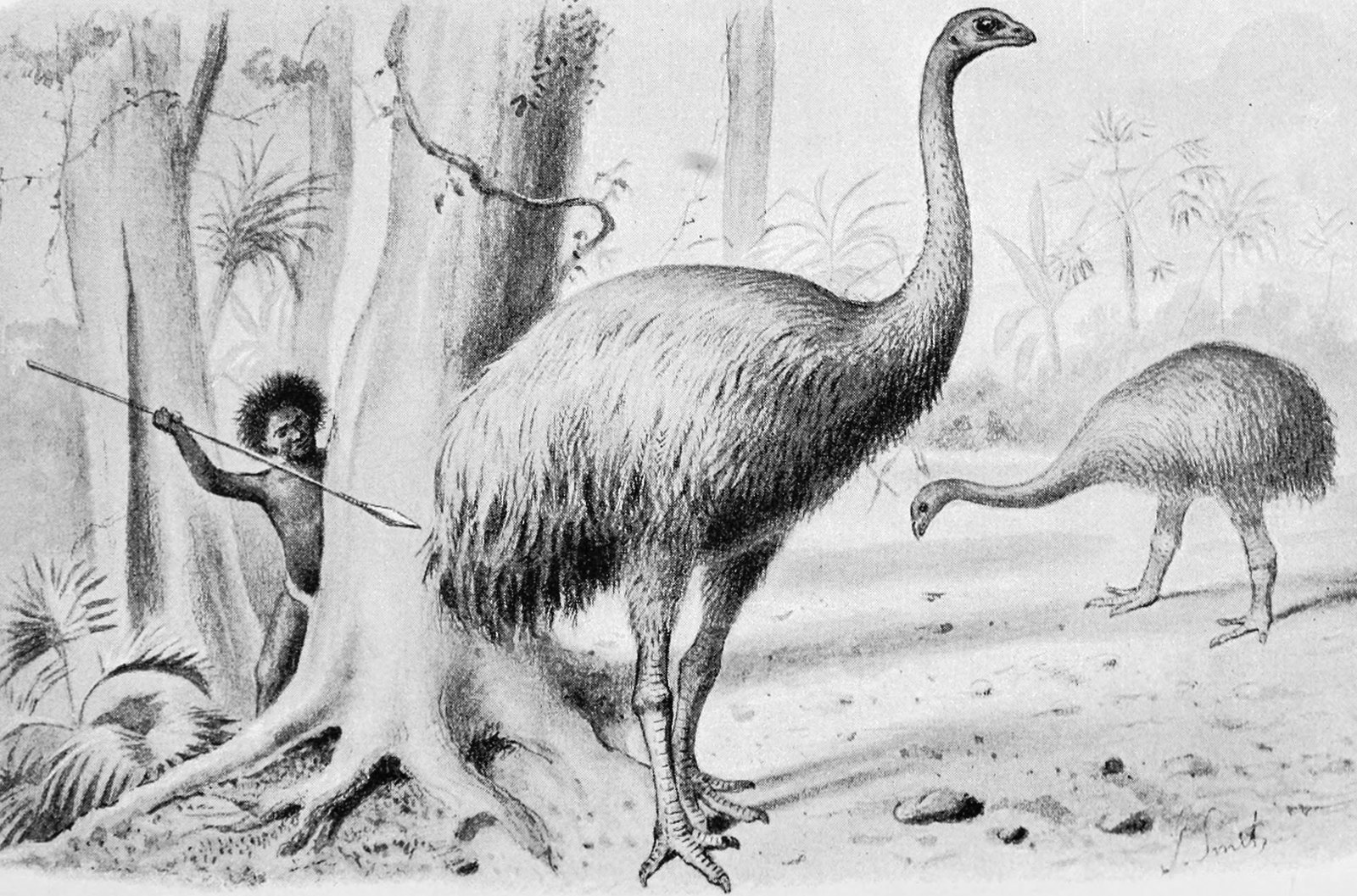

Moa of New Zealand: Vanished Within a Human Lifetime

New Zealand’s nine species of moa had no wings and, for ages, no fear of large predators. That ended when Polynesian settlers arrived in the thirteenth century with fire, dogs, and a hunter’s focus. Bones bearing butchery marks and charcoal layers reveal a blitz of overharvesting across valleys and plains. Forest burning opened land for settlement but erased the cover and forage moas needed to breed and feed. Within barely more than a century, this diverse lineage collapsed completely.

The speed of the crash still startles researchers who model population trajectories using DNA from cave remains. Even modest hunting can drive down numbers when a bird lays few eggs and matures slowly. As the moa went, so did a web of ecological roles – from seed dispersal to fern trimming – that shaped New Zealand’s forests. Their absence rewired plant communities, leaving gaps that invasive mammals later exploited. It’s a stark case of how quickly a megafauna can unravel when novel pressures arrive all at once.

Haast’s Eagle: Apex Hunter Brought Down by a Missing Prey

Built like a flying bear trap, Haast’s eagle likely specialized in taking down moa, using talons as long as a grizzly’s claws. Specialization is superb – until it isn’t. When moa disappeared, this sky-lion lost both prey and purpose, and a bird that once ruled the canopy became ecologically stranded. Habitat change and direct human impacts would have further squeezed any remnant population. In predator-prey terms, the bottom fell out of the market.

The lesson is painfully modern: food webs are only as strong as their most vulnerable link. Apex predators with narrow diets are resilient right up to the moment they’re not. Ecologists point out similar fragility today for raptors dependent on fish in warming, drought-prone waters. Haast’s eagle shows how quickly a top-tier specialist can vanish when the ladder of life loses a rung. Once the moa theater closed, the star performer had no stage left.

Argentavis magnificens: Master of the Miocene Thermals

Argentavis magnificens: Master of the Miocene Thermals (image credits: Wikimedia)

With a wingspan stretching roughly the length of a small car, Argentavis surfed hot-air highways above proto-Andean plains. Its body plan shouted efficiency: long wings for soaring, massive yet surprisingly lightweight bones, and a flight style tuned to rising thermals. But the Miocene was no forever climate. As mountains rose and wind fields shifted, the cost-benefit equation of giant flight began to change. What once was a glider’s paradise became a tougher arena for a heavyweight to master.

Unlike island giants that met people, Argentavis lived and died by geology and air. If uplift altered wind consistency or prey-rich grasslands fragmented, the energy budget could tip negative. Bigger isn’t better when you need stable skies on most days just to move and feed. Over deep time, the thermals that built the bird may have quietly unbuilt it. In fossils, we find magnificence; in absence, we find the quiet signature of a changing world.

Pelagornis sandersi: The Ocean Soarer with Pseudo-Teeth

Pelagornis looked like a sea-crossing specter from the Oligocene epoch, with wings wider than many modern gliders and bony tooth-like spines lining its beak. Those serrations gripped slippery fish and squid, turning the open ocean into a rolling buffet. But marine systems shift, and productivity bands migrate with currents and climate. A bird engineered to sip wind along narrow corridors can stumble when those corridors move or thin. For an ocean specialist, a few degrees of sea-surface change can redraw the entire map.

Pelagornithids lasted for tens of millions of years, which suggests durability, not fragility. Still, long-term declines in upwelling zones or competition as marine mammals proliferated may have tightened the margins. With huge wings comes hardware that’s costly to grow and maintain if returns drop. Evolution doesn’t punish size; it punishes inflexibility. When the ocean’s conveyor belts re-routed, the pseudo-toothed titans faded from the ledger.

Genyornis newtoni: Australia’s Thunder-Bird and the Telltale Burn Marks

Genyornis newtoni: Australia’s Thunder-Bird and the Telltale Burn Marks (image credits: wikimedia)

On Australia’s arid margins, researchers found eggshell fragments patterned with heat damage that matches campfire cooking, not wildfires. Those shards belong to Genyornis, a giant goose-like bird that shared dunes and lakes with early people roughly fifty thousand years ago. The evidence points to repeated egg harvesting that would have hit reproduction where it hurts most. Layer on a drying climate and changing vegetation, and the population’s replacement rate likely fell below zero. The bird didn’t need to be hunted to extinction when its next generation never hatched.

The debate isn’t whether climate mattered – it did – but how much human behavior accelerated the slide. Burn-pattern chemistry, ash distribution, and radiocarbon dating now paint a consistent picture of frequent human interaction. In megafaunal math, small removals multiply across years when clutch sizes are tiny. Genyornis became a victim of cumulative subtraction rather than a single strike. The dunes remember what the bones cannot say aloud.

Kelenken guillermoi: The Terror Bird with a Car-Sized Bite Radius

Kelenken wasn’t tall like an ostrich, but its skull was colossal, giving it a powerful, hatchet-like strike. In Miocene South America, these land predators filled roles later taken by big cats and canids. They hunted cursorially, likely ambushing or pursuing medium-sized mammals across open habitats. Over time, ecosystems rearranged as climates shifted and new competitors emerged through continental connections. For a lineage built on sprint-and-strike tactics, even subtle habitat mosaics can matter.

By the late Neogene, the terror birds’ heyday was waning. As placental carnivores expanded and grasslands changed, the balance tipped away from beaks toward teeth. Kelenken’s extinction story reads like a slow fade rather than a curtain drop, a product of changing arenas and new rivals. It’s the kind of turnover that repeats across deep time whenever continents collide. The fossils left behind look fierce, but permanence was never part of the deal.

Why It Matters and What Comes Next

These seven stories aren’t museum curiosities; they are case files on how giants lose. Common threads jump out: slow life histories, specialization, and landscapes that change faster than bodies can adapt. When people enter the frame, even lightly, the math grows unforgiving for species that need years to replace themselves. Today, ground-nesting birds on islands, fish-dependent raptors, and climate-tied migratory flocks face the same vulnerabilities. The past isn’t prologue – it’s a set of instructions we ignore at our peril.

What changed is our toolkit. Ancient DNA pinpoints population collapses, geochemical fingerprints on eggshells reveal human touch, and computer models test whether climate or hunting mattered more. Next-gen satellite ecology and global wind datasets can even resurrect the flight economics of giants like Argentavis. To turn lessons into action, individuals can back invasive-species control on islands, support protected area corridors that preserve thermal and foraging pathways, and fund community-led monitoring. Small choices add up when they target the exact weak points that felled the giants. The blueprint is clear enough to use, and the window to use it is open now.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.