Every so often, archaeologists stumble on a ruined city in the desert or a drowned temple off a forgotten coastline, and the same unsettling question returns: how does an entire civilization just disappear? For years, schoolbook history focused on the winners that endured – Rome, China, Egypt – while quieter cultures flickered out and slipped into the shadows. Now, with satellite surveys, ancient DNA, and geochemical tools, researchers are revisiting those shadows and finding that “collapse” is rarely simple. Instead, it is a tangled story of climate shocks, political missteps, shifting trade routes, and human resilience. The mystery has not vanished, but it has become more interesting, and far more relevant to the twenty-first century than many people realize.

The Hidden Clues of the Indus Valley Civilization

Imagine walking through a 4,000-year-old city where the streets are laid out in perfect grids, houses have private bathrooms, and drains run beneath your feet in a carefully engineered sewer system – then realizing we still cannot read a single line of its writing. That is the enigma of the Indus Valley Civilization, which flourished across what is now Pakistan and northwest India before fading out around the second millennium BCE. Excavations at major sites such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa reveal carefully planned urban centers, standardized bricks, and evidence of long-distance trade reaching Mesopotamia. Yet, there are no grand monuments celebrating kings or conquests, and the tiny seal stones covered in signs remain undeciphered. It feels a bit like finding a modern city’s server farm with all the hard drives still spinning, but none of the passwords.

For decades, textbooks simply described the Indus as a lost civilization that collapsed for unknown reasons. Recent work is more specific, pointing toward climate change and shifting rivers as crucial stressors that undercut agriculture and trade. Sediment cores and isotopic studies suggest that the once-mighty Saraswati-like river systems weakened and monsoon patterns changed over centuries, not overnight. Instead of a dramatic fall, archaeologists now see a slow dispersal: urban centers shrink, populations move eastward, crafts decentralize. The people did not vanish in a cinematic apocalypse; they adjusted and scattered, leaving behind cities that eventually eroded into those haunting “strange ruins” we stare at today.

The Maya Cities Lost in the Jungle

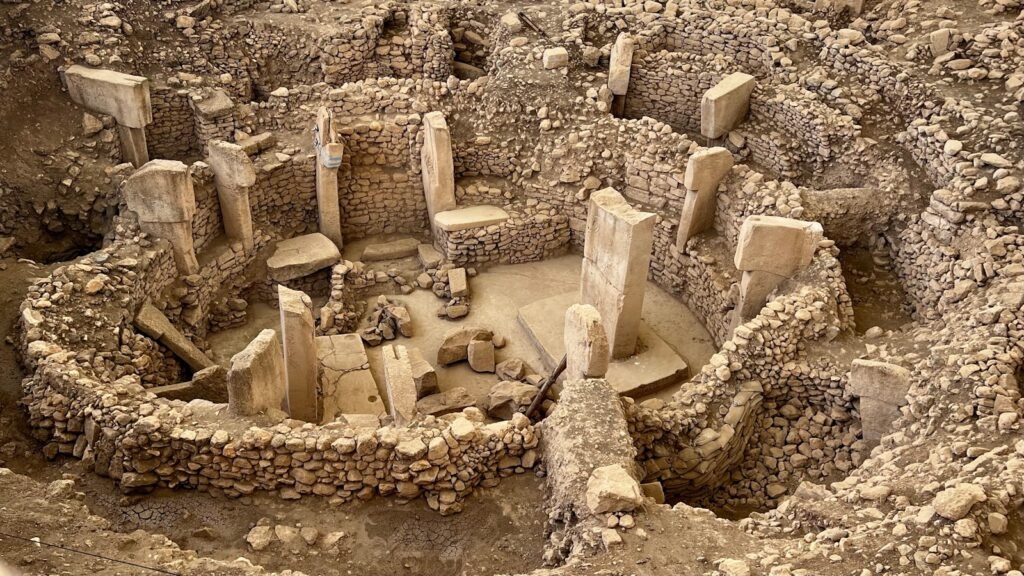

Few images capture the idea of a vanished civilization like Maya temples rising above the rainforest canopy, their stone staircases swallowed by roots and vines. Classic Maya cities, from Tikal to Palenque and Copán, once bustled with royal courts, astronomer-priests, and markets filled with cacao and obsidian. Then, between roughly the eighth and tenth centuries CE, many major lowland centers were abandoned, royal monuments stopped being carved, and political systems fractured. Early explorers turned this into a simple story of a mysterious “lost race,” which deeply distorted how we understood the region and its people. The reality, as modern Maya communities will point out, is that Maya culture did not disappear – its political map simply changed, painfully and dramatically.

Scientific tools have transformed this picture over the last two decades. Airborne laser scanning (LiDAR) revealed vast networks of causeways, terraces, and hidden structures beneath the forest, showing that Maya populations were far larger and landscapes more heavily engineered than researchers once assumed. At the same time, climate records from lake sediments and cave stalagmites show prolonged drought episodes overlapping with the timing of political collapse. Combined with evidence of soil erosion and overtaxed resources, the emerging view is that the Maya lowland collapse was a convergence of environmental stress and internal conflict, rather than a single trigger. It is less a vanishing act and more a cascade of bad years, bad decisions, and unlucky timing.

The Vanished Minoans of Bronze Age Crete

On the island of Crete, the ruins of Knossos still feel strangely alive: frescoes of leaping bulls, intricate palaces with twisting corridors, storerooms once packed with expensive goods. The Minoans were among the earliest complex societies in Europe, thriving on maritime trade across the eastern Mediterranean. For a long time, the dominant narrative held that their world was wiped out almost overnight by the eruption of the Thera volcano on nearby Santorini, in one catastrophic Bronze Age disaster. That story was dramatic and tidy, which probably explains why it stuck so firmly in the public imagination.

Recent research, however, has chipped away at the idea of a single volcanic knockout punch. Dating techniques suggest the eruption’s timing and its relationship to Minoan decline are more complicated than once believed. There is clear evidence of tsunami damage and ash fallout in some areas, but the main palatial centers seem to have continued in modified form afterward, only to falter later through a mix of economic disruption, shifting trade networks, and possibly invasion or competition from Mycenaean Greeks. In other words, the famous eruption was a major blow, but not the entire story. The Minoans did not simply vanish in smoke; their cultural DNA seems to bleed into later Aegean societies in ways researchers are still untangling.

The Nazca and the Enigma of the Desert Lines

High above the bone-dry plains of southern Peru, giant shapes stretch across the landscape: hummingbirds, monkeys, geometric lines reaching to the horizon. The Nazca people created these geoglyphs between roughly 200 BCE and 600 CE, along with complex underground aqueducts, terraced fields, and ceremonial centers. To early outsiders, the Nazca Lines seemed almost like alien calling cards because you can only really see many of them properly from the air. The real explanation is more grounded but no less fascinating, tying together ritual pathways, astronomical alignments, and water-focused ceremonies in an environment where rainfall was rare and precious. Yet by the time Spanish chroniclers arrived in the Andes, the Nazca culture itself had already faded from the political scene.

Archaeologists now think a mix of environmental instability and land-use pressure played a central role in the Nazca decline. Evidence from pollen and soil erosion suggests that as populations grew, people cleared native vegetation on fragile slopes, making the land more vulnerable when periods of drought or El Niño-driven flooding arrived. The same ingenuity that allowed the Nazca to channel scarce water may have bumped up against the hard limits of their landscape. Their disappearance as a distinct political entity did not erase their impact, though; the lines are still visible from the sky, vulnerable to modern damage from highways, mining, and careless visitors. Their story has quietly become a case study in how delicate desert ecosystems are – and how long our marks on them can last.

The Ancestral Puebloans and the Empty Great Houses

In the high desert of the American Southwest, monumental “great houses” like those in Chaco Canyon seem to rise out of nowhere – multi-story masonry complexes aligned with the sun and stars, linked by ancient roads carved through the landscape. These were built by the Ancestral Puebloans, whose societies flourished for centuries in what is now New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, and Arizona. Then, between the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, many large settlements were abandoned, and populations shifted into new social and geographic configurations. When European settlers and later tourists encountered the empty structures, they often reached for the same old line about a culture that had mysteriously vanished. That narrative ignored something obvious: living Pueblo communities still maintained oral histories and cultural connections to these very places.

Scientific work over the last several decades has reframed this so-called disappearance as a complex migration rather than an extinction. Tree-ring data shows severe, prolonged drought episodes that would have strained maize agriculture and water storage systems. Archaeologists also see signs of social tension, conflict, and changing religious practices around the same time. Instead of a single dramatic end, the evidence suggests people made strategic choices to leave vulnerable or conflicted centers and reorganize in more sustainable regions, particularly along the Rio Grande and in parts of Arizona. The “vanished” Ancestral Puebloans did not evaporate; they are the ancestors of modern Pueblo nations, whose perspectives are increasingly central to how researchers interpret those silent great houses.

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Khmer Empire

Angkor, the heart of the medieval Khmer Empire in today’s Cambodia, was once one of the largest urban complexes on Earth, laced with canals, reservoirs, and avenues of stone temples. By the fifteenth century, however, much of this urban fabric had been abandoned, and the political center had shifted downstream toward Phnom Penh. European visitors who stumbled upon Angkor centuries later were stunned by the sight of jungle-wrapped towers and carved faces peering through strangler figs. This fueled yet another romantic tale of a glorious, unknown civilization swallowed by the forest. In reality, Angkor’s story is both more gradual and more unsettling for anyone living in a rapidly urbanizing world.

LiDAR mapping has revealed that Angkor was not just a cluster of temples but a sprawling low-density metropolis, with suburban-style neighborhoods, rice fields, and reservoirs woven together. That kind of urban hydrological system is extremely powerful – and extremely fragile. Climate studies indicate alternating stretches of severe drought and intense monsoon flooding in the centuries leading up to Angkor’s decline, which likely put unbearable stress on canals and embankments. Combined with political upheaval and changing trade routes as maritime commerce grew more important, the city’s complex infrastructure seems to have become harder to maintain than it was worth. Angkor’s “vanishing” is now seen as a drawn-out unraveling of an overextended urban experiment, not an overnight catastrophe.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science: How We Investigate Vanished Worlds

What makes these vanished civilizations feel newly alive is not just the romance of ruins, but the scientific arsenal now being aimed at them. Archaeology today is far more than shovels and trowels; it is satellites, drones, chemical analyses, and massive datasets. Researchers use LiDAR to see through forest canopies, ground-penetrating radar to map buried walls, and magnetometry to detect ancient hearths. Ancient DNA extracted from bones or sediments reveals migrations and disease patterns that were simply invisible twenty years ago. Even microscopic traces of pollen, charcoal, and isotopes in lake mud can reconstruct climate swings, crop choices, and fire histories.

These tools have overturned some of the neat stories that dominated twentieth-century textbooks. Instead of blaming a single volcano, invader, or moral failing, scientists often find layered causes that unfold over generations. A typical pattern might include a gradually changing climate, a society pushing its food systems to the limit, political elites doubling down on existing strategies, and finally, a tipping point. By cross-checking different lines of evidence – tree rings against written records, soil chemistry against artifacts – archaeologists can distinguish between dramatic myths and slower, messier realities. The result is less like a simple detective story and more like reconstructing an entire ecosystem of decisions, risks, and feedback loops.

Why It Matters: Lessons From Civilizations That “Disappeared”

It is tempting to treat vanished civilizations as distant curiosities, safely sealed off in the past, but that attitude misses the point. Many of these societies were brought down, or at least badly shaken, by challenges that sound uncomfortably familiar: prolonged droughts, soil depletion, trade disruptions, and political infighting. When nearly half of a population depends on fragile water systems or imported food, small shocks can compound rapidly, just as they did in places like Angkor or the lowland Maya zones. Studying these collapses is not about doom-mongering; it is about mapping the stress points that complex societies tend to hit. The patterns show up again and again, across centuries and continents.

There is also an ethical dimension. For a long time, talk of vanished or “lost” civilizations erased the descendants who are still very much alive, from modern Maya communities to Pueblo nations and Khmer families living around Angkor’s temples. Updating the narrative matters because it changes how heritage is protected and who gets a voice in managing it. When we see ancient people only as tragic victims of fate, we overlook their creativity and capacity to adapt, migrate, and reinvent themselves. Viewing collapse as transformation, rather than pure disappearance, brings those human choices back into the story. That, in turn, sharpens how we think about our own options in the face of climate and social change.

The Future Landscape: New Technologies, Old Ruins, and Global Stakes

Looking ahead, the study of vanished civilizations is poised for another leap, driven by technology that would have sounded like science fiction a generation ago. Satellite constellations are beginning to provide near-continuous imagery that can spot subtle soil marks or vegetation changes hinting at buried structures. Machine learning tools are being trained to sift through those images, flagging potential archaeological sites almost automatically in vast, remote regions. Advances in radiocarbon dating and ancient DNA sequencing are tightening timelines and revealing population histories with startling clarity. Even underwater archaeology is expanding, with improved sonar and robotic submersibles mapping drowned coasts where early cities once stood.

These breakthroughs come with serious challenges. Many of the most vulnerable sites lie in regions facing rapid development, looting, or political instability, which means new discoveries can be destroyed almost as soon as they are identified. There are also urgent debates about data ownership, especially when high-tech surveys are conducted over lands belonging to Indigenous or local communities. Internationally, rising seas and intensifying storms threaten coastal heritage, turning time into an enemy as much as an ally. In that context, understanding how and why past societies reorganized or failed under stress becomes more than an academic puzzle. It becomes part of a global toolkit for thinking about resilience, retreat, and the hard choices that lie ahead.

How You Can Engage With the Mystery of Vanished Civilizations

You do not need a doctorate or a field hat to take part in the unfolding story of these ancient worlds. One straightforward step is to seek out museums, books, documentaries, and projects that center local and descendant voices, rather than repeating outdated myths about lost races and sudden apocalypses. Many archaeological teams now run public outreach pages, digital tours, or open data projects where curious readers can follow new findings in near real time. Supporting organizations that fight looting, illegal antiquities trafficking, and the destruction of heritage sites – whether in deserts, forests, or war zones – also makes a tangible difference. Even small choices, like being cautious about where you buy “ancient” artifacts online, help reduce demand that fuels site damage.

If you have the chance to visit ruins or historic landscapes, going with trained guides and respecting access rules protects fragile remains for the next wave of discoveries. Citizen science projects are increasingly inviting volunteers to help classify satellite images for traces of buried structures or to transcribe old excavation notes, turning curiosity into practical assistance. Reading up on the environmental histories of past collapses can also sharpen how you see the news about modern droughts, megacities, and infrastructure failures. Each of these actions is modest on its own, but together they keep the conversation about vanished civilizations firmly anchored in evidence, empathy, and shared responsibility.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.