Picture this: a quiet archaeologist brushes away centuries of dust, only to uncover a burial site that shatters everything we thought we knew about ancient people. The dead whisper secrets through their bones, and sometimes, what they say is so bizarre, so astonishing, it knocks the breath from your lungs. Across the world, ancient graves hide jaw-dropping rituals—stories of love, fear, hope, and sometimes, sheer weirdness. These aren’t just skeletons in the closet; they’re windows into the wild, surprising world of our ancestors. Ready to meet them?

The Lovers of Valdaro: Embraced for Eternity

When archaeologists uncovered a Neolithic grave near Mantua, Italy, in 2007, they couldn’t believe their eyes. Two young adults, entwined in a tender embrace, had lain together for over 6,000 years. Their skeletons, cheek to cheek and arm in arm, earned them the nickname “The Lovers of Valdaro.” Scientists found no evidence of violent death—no wounds, no trauma—leaving the cause of their demise a mystery. Some speculate they died together from illness or famine, while others romanticize their end as a tragic love story. What’s most striking, though, is the deliberate positioning, hinting at a burial ritual that honored love even in death.

The Red Lady of Paviland: Painted in Ochre

In a limestone cave on the Gower Peninsula, Wales, the so-called “Red Lady” was discovered in 1823. Despite the name, the remains actually belonged to a young man from about 33,000 years ago. His bones were stained a vivid red with ochre, a mineral pigment used in rituals worldwide. But why paint the dead? Scientists believe the ochre symbolized rebirth, protection, or a connection to the spirit world. With ivory beads and shell jewelry placed around him, the Red Lady’s burial was more than disposal—it was a carefully crafted rite, packed with meaning and perhaps a dash of prehistoric sparkle.

The Bog Bodies of Northern Europe: Preserved in Mystery

Across Denmark, Ireland, and Germany, peat bogs have yielded a parade of eerily preserved corpses from the Iron Age. These bog bodies—like Tollund Man and Lindow Man—often show signs of violent deaths: rope marks, broken bones, or even slit throats. But they weren’t just murdered; they were ritually deposited in watery graves. Experts suggest these deaths were sacrifices to appease gods, ensure good harvests, or serve as punishment. The bog’s acidic, oxygen-poor environment preserved hair, skin, and even stomach contents, allowing scientists to reconstruct their final meals and last moments in haunting detail.

The Sunghir Burials: Children Covered in Ivory

In Russia, the Upper Paleolithic site of Sunghir unveiled a grave that stunned archaeologists. Two children, aged about 12 and 13, were laid head-to-head, swaddled in thousands of mammoth ivory beads. Each bead took hours to make, suggesting months or even years of preparation for the burial. The lavish grave goods—delicate spears, animal figurines, and ornate jewelry—hint at a society that revered these young ones. Were they nobility, shamans, or symbols of hope? The sheer effort poured into these burials suggests a ritual far deeper than simple mourning.

The Massacre at Talheim: Signs of Ancient Warfare

In the German village of Talheim, a 7,000-year-old grave holds the remains of 34 individuals, their skulls crushed and limbs broken. This was no ordinary burial—it was the aftermath of a massacre. Men, women, and children were dumped in a pit, their bones telling a chilling story of violence. Archaeologists believe this was a prehistoric raid, possibly over land, resources, or revenge. Yet even after such brutality, the community honored the dead with burial, suggesting that ritual and respect could coexist with the harsh realities of survival.

The Lady of Cao: Tattooed Priestess of Peru

In 2006, beneath a pyramid at El Brujo in Peru, archaeologists discovered a mummy wrapped in layers of cloth and mystery. The Lady of Cao was a high-ranking priestess who died around 1,700 years ago. Her skin bore intricate tattoos of snakes, spiders, and supernatural beings. She was buried with weapons, jewelry, and ceremonial objects, indicating immense status. The presence of these ritual items alongside her tattooed body challenges old notions of gender roles in ancient Peru, revealing a world where women could wield both power and sacred authority.

The Mysterious Headless Romans of York

In Roman-era York, England, more than 80 skeletons were found—each missing its head. Many skulls lay between the legs or at the feet of the bodies. For years, this baffled scientists. Were these criminals, gladiators, or ritual sacrifices? Isotope analysis of their bones revealed many had traveled great distances, hinting at a diverse, cosmopolitan population. Some believe the decapitations were part of a funerary rite, meant to help souls cross into the afterlife. Others argue it was a mark of dishonor or a warning to others. Whatever the reason, the headless burials remain one of Britain’s strangest ancient puzzles.

The Dog Burials of Ashkelon: Honoring Man’s Best Friend

In the ancient port city of Ashkelon, Israel, archaeologists found a cemetery like no other: hundreds of carefully buried dogs, spanning centuries. Each dog was laid on its side, sometimes with grave goods, and never with signs of sacrifice or violence. This suggests the dogs were cherished companions, not just working animals. The practice is so unique that some researchers believe the people of Ashkelon revered dogs as sacred, healers, or even guardians of the underworld. It’s a touching reminder that love for animals stretches far back into human history.

The Chauchilla Necropolis: Shrouded in Sitting Silence

In the Peruvian desert, the Chauchilla Necropolis holds mummies that sit upright, knees drawn to their chests, wrapped in textiles and gazing through empty eye sockets. The arid conditions and ritual use of resin preserved them for over a thousand years. The seated posture was no accident—it symbolized readiness for rebirth or the journey to the afterlife. Offerings of food, ceramics, and personal belongings surrounded the dead. These burials paint a vivid picture of Nazca beliefs, where death was not the end, but a transition to another world.

The Mass Graves of Çatalhöyük: Buried Beneath the Floor

In the Neolithic city of Çatalhöyük, Turkey, residents buried their dead directly under their homes. Skeletons were placed beneath packed mud floors, sometimes in groups, with personal objects or painted shells. This intimate practice suggests a deep connection between daily life and the realm of ancestors. Some houses held generations of bones, blurring the lines between the living and the dead. Scientists believe this tradition reinforced family ties and community identity, making every home a sacred space.

The Viking Ship Burials: Voyages into the Afterlife

When Vikings of high status died, they were sometimes set to sea—literally. Ship burials, like the famous Oseberg and Gokstad finds in Norway, involved laying the deceased in a boat with weapons, jewelry, and even sacrificial animals or slaves. The ship symbolized a journey to Valhalla, the hall of the gods. These burials were grand spectacles, reflecting both spiritual beliefs and the power of the deceased. The scale and artistry of the vessels underscore the importance of ritual and honor in Viking society.

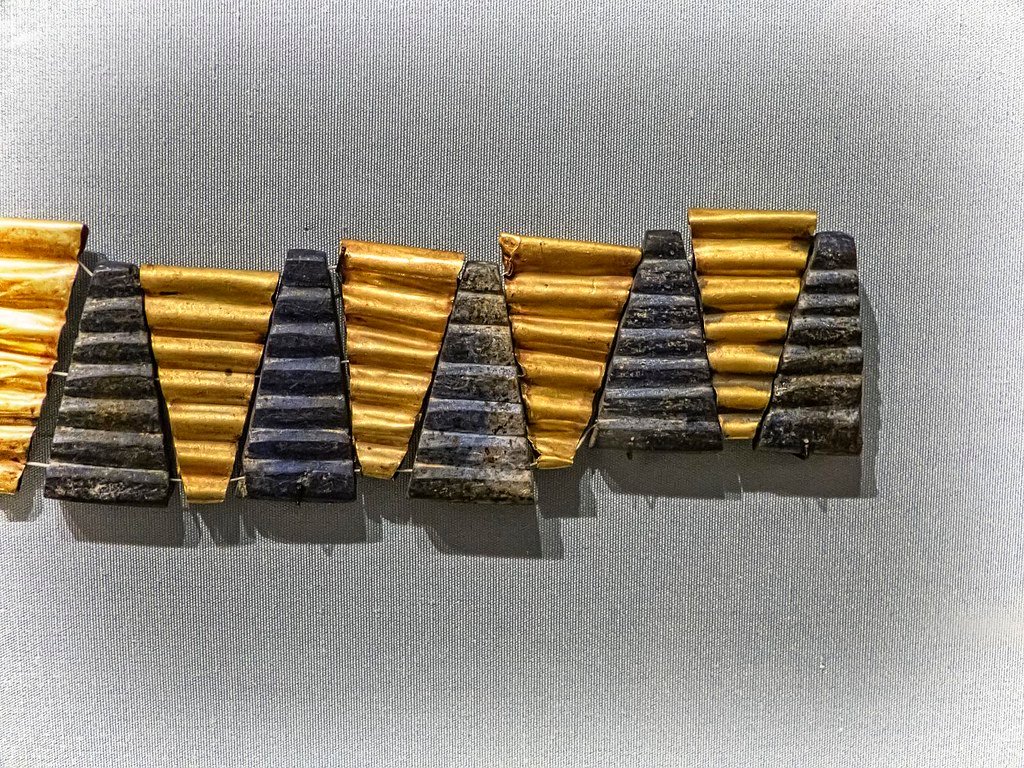

The Silla Gold Crowns: Royalty in Death

In South Korea’s ancient Silla Kingdom, archaeologists have unearthed tombs filled with stunning gold crowns, belts, and weapons. These dazzling treasures were buried with kings, queens, and nobles, signifying their divine connection and authority. The elaborate ornaments, studded with jade and shaped like trees or antlers, hint at shamanistic rituals. The craftsmanship and opulence of Silla burials reveal a society where death was marked by both reverence and an explosion of artistic expression.

The Double Burial at Dolní Věstonice: Twinned by Fate

In the Czech Republic, a 27,000-year-old grave holds two young males, their bodies positioned side by side with touching arms. One had a physical disability, and scientists believe he was cared for by his community. Grave goods and the odd arrangement suggest special status or a ritual bond—perhaps brothers, companions, or members of a shamanic order. The burial offers a poignant glimpse of prehistoric compassion, and hints at the spiritual significance ancient people placed on togetherness, even in death.

The Painted Skulls of Jericho: Faces from the Past

Early farmers in Jericho, over 9,000 years ago, practiced a ritual both unsettling and beautiful. After the flesh decayed, they removed skulls from the graves, plastered them with clay, and painted them to resemble lifelike faces. Shells replaced eyes, and features were molded by hand. These skulls were displayed in homes or shrines, serving as ancestral totems. The act transformed the dead into guardians or spiritual intermediaries, keeping family close in a world where survival depended on unity and tradition.

The Royal Tombs of Ur: Death Pits and Divine Drama

Excavations at Ur, in present-day Iraq, exposed royal burials dating from 4,500 years ago, complete with golden treasures, elaborately dressed attendants, and even oxen. Some tombs, like that of Queen Puabi, included “death pits” where dozens of servants were buried alongside their ruler. The scale and spectacle of these burials suggest rituals of sacrifice, loyalty, and the belief that rulers continued their reign in the afterlife. The drama and opulence of Ur’s graves are a testament to the ancient world’s blend of power and piety.

The Child Sacrifices of the Inca: Frozen on the Peaks

High in the Andes, archaeologists have found the frozen bodies of Inca children, sacrificed atop volcanoes over 500 years ago. Clad in fine textiles and surrounded by offerings, these children were chosen for their purity and beauty. The Incas believed their sacrifice ensured the favor of the mountain gods and the fertility of the land. Modern analysis shows they were drugged before death, making their final moments peaceful—or at least, numb. The practice reveals a world where faith demanded the ultimate price.

The Jar Burials of Ban Non Wat: Infants in Pots

At Ban Non Wat in Thailand, Neolithic families buried their infants in large ceramic jars, sometimes accompanied by beads or small toys. The jars protected the tiny bodies, perhaps symbolizing a return to the womb or the earth’s embrace. This gentle, poignant ritual suggests deep parental love and the hope for rebirth. The practice also highlights how societies found meaning and comfort in the face of heartbreaking loss.

The Warrior Women of the Scythians: Graves of the Amazons

Scythian burial mounds across the Eurasian steppe often contain female skeletons interred with weapons, armor, and horses. Some of these women bore battle wounds, confirming that ancient tales of warrior women—Amazons—weren’t just legend. The graves show a society where gender roles could be fluid, and where women might fight, lead, and be honored as warriors. These discoveries challenge our ideas about ancient gender norms and the power of myth.

The Cannibal Caves of Gough’s Cave: Ritual Consumption?

Deep in Gough’s Cave, England, human bones from 14,700 years ago bear marks of butchery and cannibalism. Skulls were carefully modified into cups, while other bones show deliberate breaking and scraping. Was this desperation, ritual, or both? Some scientists argue the practice was ceremonial—a way to absorb the strength of the dead or honor ancestors. The evidence is grisly, but it offers a rare glimpse into the extremes of ancient ritual.

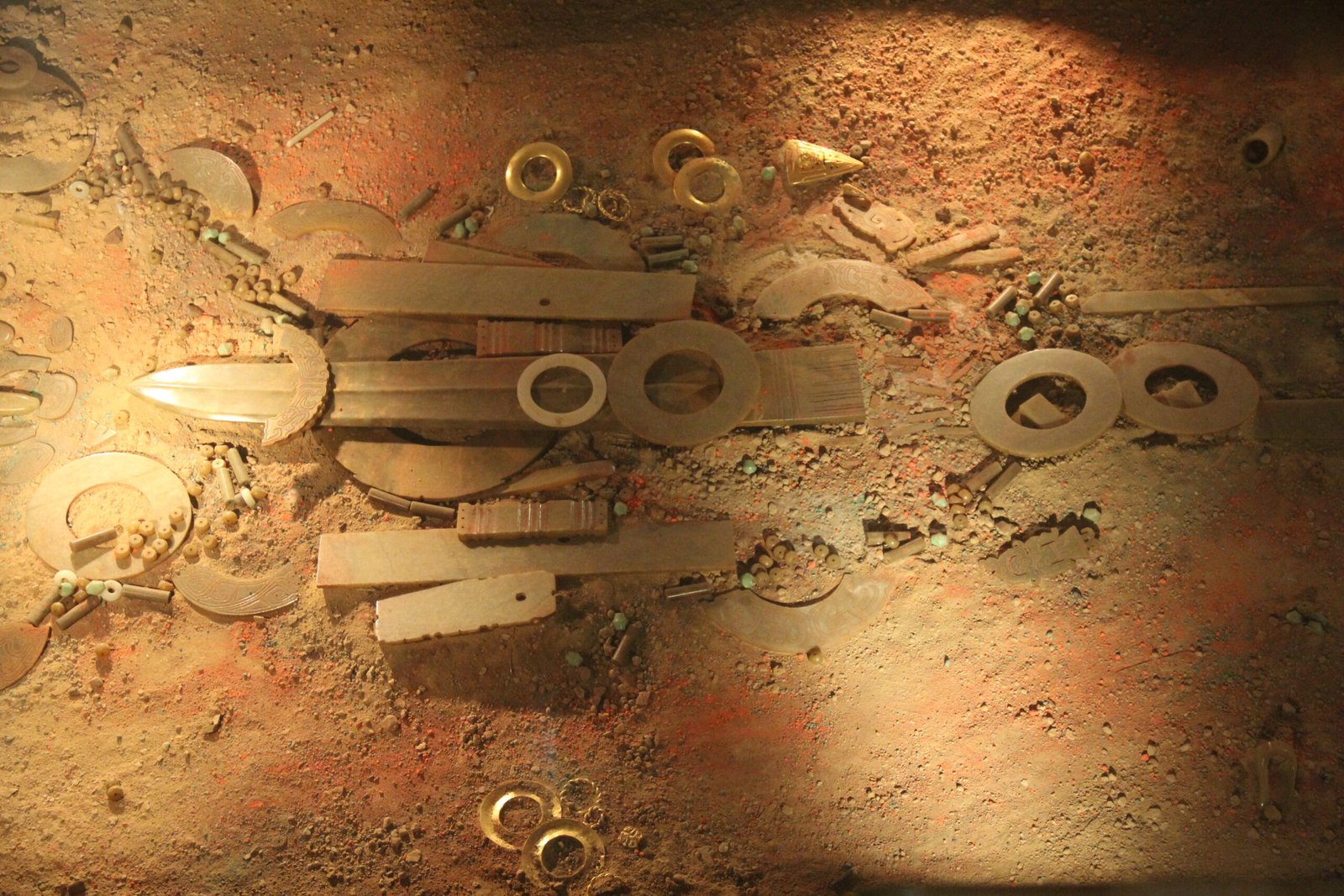

The Moche Sacrifice Burials: Blood and Ceremony

On Peru’s north coast, the Moche civilization practiced ritual human sacrifice, burying victims on temple platforms. Recent finds at Huaca de la Luna show rows of young men with slashed throats, buried with ceremonial objects and pigments. Iconography suggests these sacrifices were part of elaborate public rituals to appease gods or ensure rain. The mix of violence, pageantry, and faith in these burials reveals the complex, often brutal, logic of ancient religion.

In every corner of the ancient world, burial rituals reveal stories as wild and varied as humanity itself. From painted skulls to frozen sacrifice, these graves aren’t just about death—they’re about what it meant to live, to believe, and to belong in a world both familiar and utterly strange.