Across the Americas, long before Europeans arrived, entire civilizations rose, flourished, and then disappeared so completely that for centuries people had no idea they had ever existed. Ruined temples swallowed by jungle, pyramids buried under farmland, and ghost cities in deserts tell a story that feels almost like a supernatural thriller. Yet what really happened to these people is not magic at all – it is climate, politics, belief, and sometimes pure bad luck.

What makes these vanished cultures so gripping is how much we still don’t know. Archaeologists keep finding new cities from the sky using laser-scanning planes, decoding forgotten symbols, and reading the story left in bones, pollen, and broken pottery. The closer we look, the more unsettling the pattern becomes: powerful societies can crumble shockingly fast. Let’s dive into seven of the most mysterious cases and see what they might be trying to tell us about our own fragile moment in history.

The Olmec: The “Mother Culture” That Melted Into Mystery

The Olmec flourished along the Gulf Coast of what is now Mexico more than three thousand years ago, long before the Maya or the Aztec reached their peaks. They carved enormous stone heads weighing many tons, with faces so expressive they feel like portraits of individuals you could almost meet on the street today. They built complex ceremonial centers like San Lorenzo and La Venta, developed early writing signs, and probably laid the groundwork for the famous Mesoamerican ballgame. In many ways, they were the blueprint for later civilizations in the region.

And then, around two and a half millennia ago, their major cities were abandoned, their colossal heads toppled or left half-buried, and their name vanished from living memory. There’s no clear record of invasion or sudden catastrophe; instead, researchers suspect a tangled mix of river changes, environmental decline, internal tensions, and shifting trade routes. Later cultures borrowed and adapted Olmec ideas so thoroughly that the Olmec themselves faded into the background, like a ghost writer who never gets a credit line. It’s a reminder that sometimes a civilization disappears not with a bang, but by being quietly absorbed and forgotten.

Cahokia: The Lost City of Mounds in the American Heartland

Just across the river from present-day St. Louis once stood the largest urban center north of Mesoamerica: Cahokia. Around one thousand years ago, this city of massive earth mounds, wooden palisades, and wide plazas may have housed tens of thousands of people. At its heart was Monks Mound, a gigantic earth pyramid bigger in base area than the Great Pyramid in Egypt. Cahokia’s residents farmed maize, traded over vast distances, and practiced elaborate rituals that shaped life and death across the Mississippi Valley.

Yet within a few centuries, the city was abandoned and its mounds slowly eroded into the landscape, so completely that for a long time many outsiders assumed Indigenous North America had never seen large cities at all. Evidence points to a dangerous mix of overexploited resources, flooding, social inequality, and perhaps political or religious upheaval that made the dense urban experiment unsustainable. When I first visited the site, looking out from the top of Monks Mound at modern highways and suburbs, it felt surreal to imagine a vanished skyline of wooden temples in the same spot. Cahokia’s rise and fall almost feels like a rehearsal for modern boom-and-bust cities built on fragile foundations.

Teotihuacan: The City of the Gods with No Known Rulers

Teotihuacan, just outside modern Mexico City, was once one of the largest cities anywhere on Earth, with grand pyramids and a broad central avenue that still stuns visitors today. At its height, roughly about one fifth of the entire population of central Mexico may have lived in or around this sprawling metropolis. Its people constructed the Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon, painted entire apartment compounds in vivid murals, and influenced art and politics as far away as the Maya world. To later cultures, its ruins were so impressive that they believed gods, not humans, must have built them.

But we still do not know what the original inhabitants called their city, what language they spoke, or even how their government worked; no clear royal tombs or named kings have ever been firmly identified. Sometime around the sixth century, fires swept through elite compounds, and over the next century or two the city shrank drastically before being largely abandoned. Archaeologists suspect drought, political revolt, fraying trade networks, and class tensions may have all played a role in the unraveling. Standing at the top of the Pyramid of the Sun today, you look over a silent grid where the voices of maybe a hundred thousand people once echoed – yet their names and stories have mostly dissolved, leaving only stone and guesswork behind.

Tiwanaku: The High-Altitude Enigma by Lake Titicaca

At over twelve thousand feet above sea level near Lake Titicaca, the Tiwanaku civilization pulled off something that still seems almost impossible: they built a powerful state in one of the world’s harshest highland environments. Their architects crafted precisely cut stone blocks that fit so tightly together you couldn’t slide a blade between them, creating temples like the Akapana and Kalasasaya that align with the sun and seasons. The Tiwanaku people engineered raised-field agriculture to protect crops from frost, turning cold wetlands into productive farmland. Their influence spread widely through the Andes, not just by military conquest but also through trade and religious networks.

Then, around the eleventh century, their urban core emptied out and monumental construction stopped, leaving scattered stones and a scattering of later myths. Many researchers now see a long period of climate instability and drought as a central trigger, undermining the finely tuned agricultural systems that supported Tiwanaku’s population. Political fragmentation, rival centers, and perhaps religious disillusion may have followed, as faith in old rituals failed to bring back the rains. When I read about Tiwanaku’s decline, it feels uncomfortably familiar: a society deeply dependent on climate-sensitive technology suddenly pushed beyond its limits, with very little margin for error.

The Nazca: Masters of the Desert Lines Who Left No Farewell

In the bone-dry deserts of southern Peru, the Nazca people created one of the world’s most bizarre and captivating cultural signatures: giant lines and figures etched into the earth, visible best from the sky. They also built complex underground aqueducts, cultivated cotton and maize, and developed a distinctive pottery style with bold, almost psychedelic designs. Their culture thrived for many centuries in a landscape where one failed rainy season could mean disaster. Managing water and soil was not a side issue for them; it was the core of survival and belief.

Sometime after roughly fifteen hundred years ago, Nazca society began to fracture and fade, their geoglyphs left to be scoured by wind and dust. Climate records suggest intense El Niño events and shifting rainfall patterns that may have triggered floods, erosion, and crop failures, especially in areas where deforestation stripped hillsides of protection. When environmental stress hit, social tensions and competition with neighboring cultures likely escalated, accelerating the breakdown. The strangest part is that the Nazca lines themselves kept surviving while the people who created them did not – a haunting reminder that landscapes sometimes remember what living communities cannot hold on to.

The Classic Maya Cities: Collapses in the Jungle

The Classic Maya built soaring temples, carved sophisticated hieroglyphs, and computed astronomical cycles with an accuracy that still impresses scientists today. From Palenque and Tikal to Copán and Calakmul, their rainforest cities were political powerhouses locked in rivalry, alliance, and ritual spectacle. Their rulers inscribed their own deeds in stone, so we know their names, their wars, and even some personal dramas. For a long time, people imagined the Maya as a peaceful priestly society, but the deciphered texts revealed them as ambitious, sometimes brutal, and very human.

Between roughly the eighth and tenth centuries, many of these great lowland cities were gradually abandoned, their plazas swallowed by jungle vines and tree roots. The picture that has emerged is messy: cycles of warfare, severe droughts, overuse of fragile soils, and the heavy burden of supporting elite lifestyles all contributed to political collapse. Some regions depopulated sharply, while others shifted power northward or into new centers, so it was not a simple overnight disappearance. What unsettles me about the Classic Maya collapses is how they show a complex, literate, and innovative society failing to adapt fast enough to a changing climate and its own internal contradictions, despite all its knowledge.

The Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi): Empty Cliff Cities of the Southwest

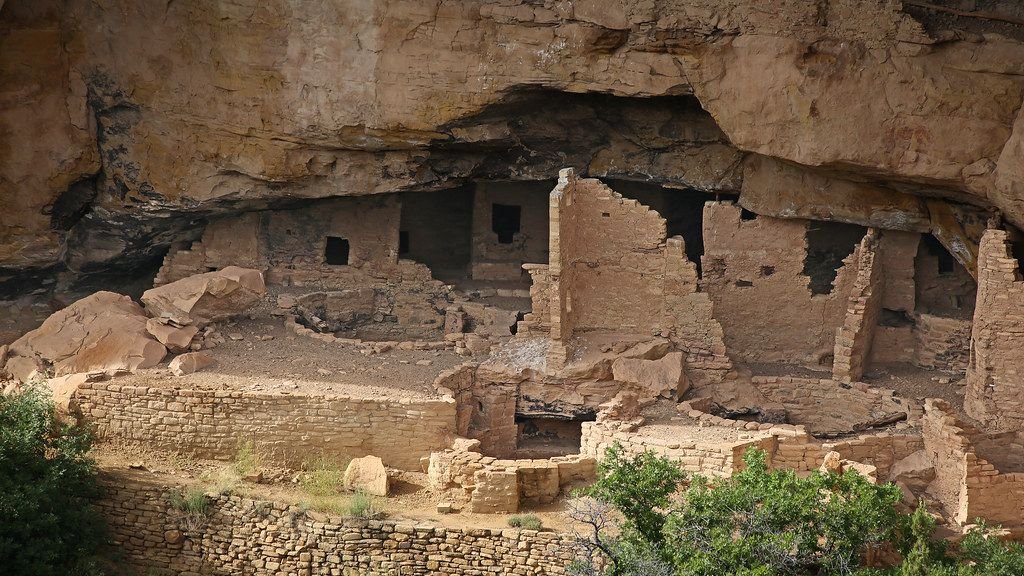

In the canyons and mesas of the American Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans built remarkable stone dwellings tucked into cliff faces and laid out planned towns with kivas, plazas, and multi-story housing. Places like Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde were carefully organized, linked by long roads and shared ceremonial traditions. For centuries, they managed dryland farming with a level of care that feels almost like a partnership with the land rather than a conquest of it. Socially, they seem to have relied more on ritual and community structures than on heavily armed kings or obvious empires.

By the late thirteenth century, many of these major centers were abandoned, leaving only silent rooms and ladders leading nowhere. Tree rings and other climate evidence point strongly to prolonged droughts, possibly combined with episodes of conflict, resource scarcity, and shifting trade connections, as key pressures pushing people to migrate. The descendants of these communities did not vanish entirely; many modern Pueblo peoples trace connections to these ancestors, even though the old cities themselves were left behind. When you stand in a cliff dwelling today, staring at blackened hearths and handprints on the walls, it’s hard not to wonder what it felt like to lock the door for the last time and walk away into an uncertain future.

In the end, these seven vanished civilizations are not just ancient puzzles; they are cautionary mirrors. They show how power, creativity, and knowledge do not guarantee survival when climate shifts, resources are strained, and social systems become too rigid to bend. Their cities may be ruins now, but their stories are still unfolding in the dust, the stone, and the questions we keep asking. Did you expect that?