Picture this: a world without the thunderous roar of a California condor soaring overhead, or the gentle splash of an Arabian oryx drinking from a desert oasis. These scenes almost became permanent memories rather than living realities. While critics often question the role of modern zoos, there’s an incredible untold story of rescue, dedication, and scientific triumph happening behind those glass barriers and carefully maintained habitats.

The Unlikely Heroes Behind Bars

When most people think about zoos, they imagine families pointing at exotic animals or children pressing their faces against aquarium glass. What they don’t see is the sophisticated network of geneticists, veterinarians, and conservation biologists working around the clock to prevent species from vanishing forever. Modern zoos have transformed from simple entertainment venues into high-tech conservation centers equipped with cryogenic storage facilities, specialized breeding programs, and satellite tracking systems.

These institutions now function as modern-day Noah’s arks, maintaining genetic diversity through carefully managed breeding programs. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums coordinates these efforts globally, ensuring that genetic material from different populations gets mixed to prevent inbreeding. It’s like having a massive, international dating service for endangered species.

California Condor: Rising From Nine Birds

The California condor’s story reads like a medical thriller with a happy ending. In 1987, the species hit rock bottom with only nine individuals remaining in the wild. These magnificent birds, with wingspans reaching nearly ten feet, were dying from lead poisoning, habitat loss, and collisions with power lines. The situation was so desperate that wildlife officials made the controversial decision to capture every single wild condor.

The San Diego Zoo and Los Angeles Zoo became the species’ intensive care units. Scientists had to hand-rear chicks using condor puppets to prevent the birds from imprinting on humans. They developed specialized diets, created artificial nesting sites, and even taught young condors how to avoid power lines using aversion training. Today, over 500 California condors exist, with more than 300 flying free across California, Arizona, and Utah.

Arabian Oryx: Back From the Brink of Forever

The Arabian oryx holds the remarkable distinction of being the first species to be downgraded from “Extinct in the Wild” to “Vulnerable” on the conservation status scale. These elegant white antelopes with their distinctive straight horns once roamed the Arabian Peninsula in large herds. By 1972, hunting and habitat destruction had eliminated them completely from their natural habitat.

Phoenix Zoo stepped up as the species’ guardian, starting with just four animals captured from the wild in the 1960s. The breeding program required incredible patience and scientific precision. Female oryx only reproduce once a year, and the gestation period lasts about eight months. Zoo scientists had to learn everything about oryx behavior, from their social structures to their ability to detect rainfall from miles away.

The reintroduction process began in 1982 in Oman, where carefully selected zoo-bred oryx were released into protected reserves. These animals had to relearn survival skills their captive-born parents never possessed, like finding water sources and avoiding predators.

Golden Lion Tamarin: Brazil’s Comeback Kid

With their flowing golden manes and expressive faces, golden lion tamarins look like tiny lions that belong in fairy tales rather than reality. These small primates, weighing less than two pounds, once swung through Brazil’s Atlantic coastal forests in large family groups. Deforestation reduced their habitat by 95%, leaving fewer than 200 individuals by the 1970s.

The National Zoo in Washington D.C. pioneered the tamarin breeding program, but success didn’t come easily. These primates have complex social structures and specific dietary needs that took years to understand. Scientists discovered that tamarins require live insects in their diet and need large family groups to properly raise their young. The breakthrough came when researchers learned to simulate the tamarins’ natural forest environment, complete with hiding spots, climbing structures, and seasonal temperature variations.

Black-Footed Ferret: America’s Rarest Mammal

The black-footed ferret earned the unfortunate title of North America’s rarest mammal, and for good reason. These sleek predators depend almost entirely on prairie dogs for food, and when ranchers and farmers systematically eliminated prairie dog colonies, the ferrets vanished too. By 1979, scientists believed the species was extinct.

Then, in 1981, a ranch dog in Wyoming brought home a dead ferret, sparking one of the most intensive captive breeding efforts in conservation history. The National Black-footed Ferret Conservation Center had to work with just 18 individuals, creating a genetic bottleneck that required careful management. Scientists learned that ferrets are incredibly social animals that need to play and interact with their siblings to develop proper hunting skills.

The breeding program faced numerous challenges, including an outbreak of canine distemper that nearly wiped out the entire captive population. Veterinarians had to develop new vaccines specifically for ferrets and create quarantine protocols that would make a hospital proud.

Przewalski’s Horse: The Last True Wild Horse

Przewalski’s horses represent something extraordinary in the animal kingdom: they’re the last truly wild horses on Earth, never domesticated by humans. These stocky, tan-colored horses with distinctive dark manes once roamed the steppes of Mongolia and northern China. Unlike domestic horses, they have 66 chromosomes instead of 64, making them genetically distinct from any horse in your local stable.

By the 1960s, these horses had disappeared from the wild entirely. European zoos became their salvation, working with a foundation stock of just 14 individuals captured in the early 1900s. The Munich Zoo led the international breeding program, meticulously tracking bloodlines to maintain genetic diversity. Scientists used computer modeling to determine which horses should breed with whom, essentially playing genetic matchmaker for an entire species.

The Science Behind the Miracle

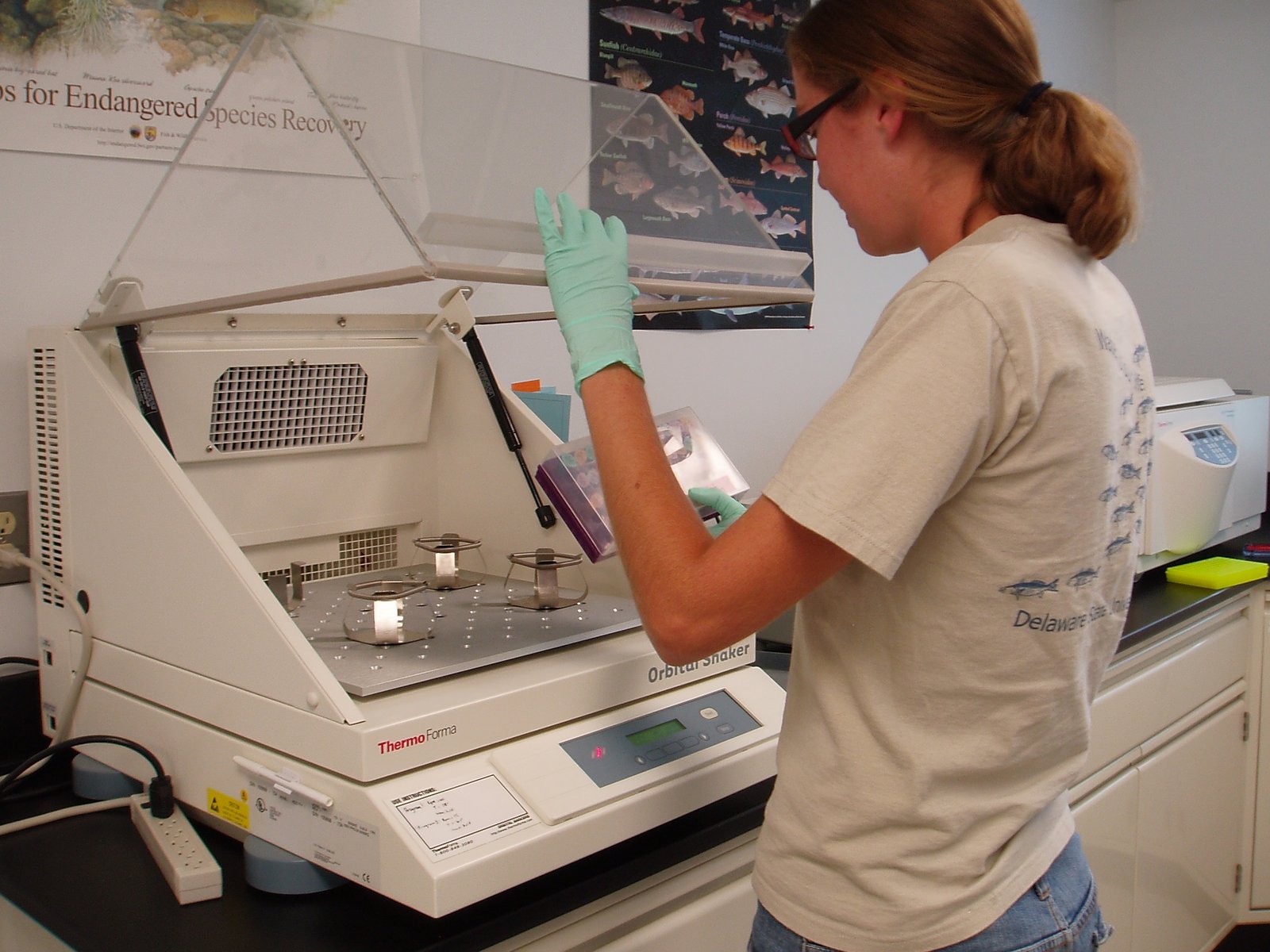

Modern zoo conservation relies on cutting-edge technology that would make science fiction writers jealous. Cryogenic freezing preserves genetic material from animals for decades, creating biological time capsules that can be used long after the original animal has died. Some facilities maintain “frozen zoos” containing samples from thousands of species, including some that are now extinct.

Artificial insemination techniques allow zoos to breed animals without the stress of transportation. A female elephant in Thailand can be impregnated with genetic material from a male elephant in Kenya, maintaining genetic diversity across continents. Scientists also use hormone monitoring to time breeding perfectly, increasing success rates dramatically.

Genetic Detectives at Work

Every animal in a modern conservation breeding program has a genetic passport more detailed than most humans’ medical records. Scientists analyze DNA to determine which individuals should breed together, avoiding the genetic problems that come with small populations. They can identify carriers of genetic diseases, determine parentage with absolute certainty, and even predict which offspring will be best suited for release into the wild.

This genetic sleuthing extends to wild populations too. When scientists release zoo-bred animals back into nature, they use genetic markers to track how well the animals integrate with existing wild populations. It’s like following a complex family tree that spans continents and generations.

The Psychology of Survival

Breeding endangered species isn’t just about biology; it’s about psychology too. Animals born in captivity often lack the survival instincts their wild counterparts take for granted. Zoos have developed innovative training programs to teach captive-bred animals essential skills like predator recognition, foraging techniques, and social behaviors.

California condor chicks learn to fear humans through careful conditioning, while black-footed ferret kits practice hunting live prey in specially designed enclosures. Some programs use “mentor” animals – individuals captured from the wild – to teach captive-bred animals proper behaviors. It’s like having experienced teachers showing newcomers the ropes.

Technology Meets Conservation

Today’s conservation programs use satellite tracking, GPS collars, and even drones to monitor released animals. Scientists can track individual animals 24/7, learning about their behavior patterns, territory sizes, and social interactions. This data helps improve future release programs and identifies potential problems before they become critical.

Some facilities use virtual reality systems to help animals adapt to new environments before release. Cameras placed in release sites allow captive animals to “visit” their future homes, reducing stress when they actually arrive. It sounds like something from a futuristic movie, but it’s happening right now in conservation centers around the world.

The Network Effect

No single zoo can save a species alone. Modern conservation operates through complex international networks where zoos, universities, government agencies, and conservation organizations share resources, knowledge, and animals. The European Endangered Species Programme coordinates breeding efforts across hundreds of facilities, ensuring genetic diversity and preventing duplication of efforts.

These networks also share failures and successes openly. When a breeding technique works at one facility, the information spreads quickly to others. When problems arise, the entire network mobilizes to find solutions. It’s like having a global emergency response team for endangered species.

Measuring Success Beyond Numbers

Conservation success isn’t just about increasing population numbers; it’s about creating self-sustaining wild populations that can survive without human intervention. Scientists measure success through genetic diversity, reproductive rates, survival to adulthood, and the ability of released animals to produce viable offspring in the wild.

Some species, like the California condor, still require ongoing management with supplemental feeding and medical care. Others, like certain populations of Arabian oryx, have become truly self-sufficient. The ultimate goal is always independence from human care, but the path there varies dramatically between species.

Economic Impact of Conservation

Conservation breeding programs represent massive financial investments that span decades. The California condor program has cost over $35 million since its inception, while the Arabian oryx program required international funding from multiple governments and conservation organizations. These programs employ hundreds of scientists, veterinarians, and support staff worldwide.

However, the economic benefits extend far beyond the immediate conservation efforts. Ecotourism generates billions of dollars annually, much of it driven by people wanting to see these rescued species in their natural habitats. The techniques developed for endangered species breeding also benefit domestic animal breeding and human medical research.

Challenges That Keep Scientists Awake

Despite remarkable successes, conservation breeding faces enormous challenges. Climate change is altering habitats faster than animals can adapt. Political instability in some regions makes reintroduction programs dangerous or impossible. Habitat destruction continues despite conservation efforts, leaving animals with nowhere to go even if their populations recover.

Some species prove incredibly difficult to breed in captivity. Giant pandas famously have brief fertility windows and complicated mating behaviors. Other species suffer from genetic bottlenecks so severe that maintaining healthy populations becomes nearly impossible. Each species presents unique puzzles that can take decades to solve.

The Ripple Effect

Saving individual species creates ripple effects throughout entire ecosystems. When Arabian oryx returned to the wild, they helped maintain grassland habitats that support dozens of other species. California condors serve as indicators of ecosystem health, helping identify environmental problems that affect many species simultaneously.

These flagship species also generate public support for broader conservation efforts. People who might not care about habitat preservation become passionate advocates when they learn about individual species’ survival stories. A single charismatic species can drive funding and support for protecting entire ecosystems.

Future Frontiers

The next generation of conservation technology promises even more dramatic possibilities. Gene editing techniques might allow scientists to increase genetic diversity in small populations or even remove genetic diseases entirely. Advances in reproductive technology could make breeding programs more efficient and successful.

Some researchers are exploring the possibility of using preserved genetic material to revive recently extinct species. While true “de-extinction” remains controversial and technically challenging, the techniques being developed could help current conservation efforts. The boundary between science fiction and conservation reality continues to blur.

What This Means for Tomorrow

The success stories of these five species prove that extinction doesn’t have to be forever – at least not yet. Modern zoos have evolved into sophisticated conservation centers capable of pulling species back from the brink of disappearance. However, these victories come with enormous costs in time, money, and scientific expertise.

The real lesson isn’t just that we can save species after they’ve nearly vanished, but that prevention remains far more effective than rescue. The California condor program, while successful, costs more per bird than many entire habitat protection programs. Each of these conservation victories represents both human ingenuity at its finest and a reminder of how much we’ve already lost.

These rescued species now serve as living ambassadors for conservation, inspiring new generations of scientists and conservationists. They prove that individual actions can have global impacts and that seemingly impossible challenges can be overcome with dedication, resources, and time. What started as desperate last-ditch efforts have become models for conservation programs worldwide.

When you see a California condor soaring overhead or watch Arabian oryx grazing in desert preserves, you’re witnessing something truly remarkable: extinction reversed. How many other species could we save if we started acting before they reached single-digit populations?