You might be surprised to learn that the blueprint for American democracy wasn’t solely crafted in dusty European libraries or drawn exclusively from ancient Greek philosophers. Long before the Founding Fathers gathered in Philadelphia to debate the future of a new nation, something remarkable was already thriving on this continent. A sophisticated system of government had been flourishing for centuries in what we now call upstate New York, maintained by Indigenous peoples who had mastered the art of democratic governance while Europe was still ruled by monarchs and emperors.

The Iroquois Confederacy, founded by the Great Peacemaker in 1142, is the oldest living participatory democracy on earth. Think about that for a moment. We’re talking about a functioning democracy that predates European contact by hundreds of years. In 1988, the U.S. Senate paid tribute with a resolution that said, “The confederation of the original 13 colonies into one republic was influenced by the political system developed by the Iroquois Confederacy, as were many of the democratic principles which were incorporated into the constitution itself.”

This isn’t just a feel good story about cultural exchange. It’s a fundamental rewriting of how we understand the origins of American government. So let’s dive into the specific ways these Indigenous nations shaped the democracy you live under today.

The Federal System Where Unity Meets Autonomy

One of the primary ways the Iroquois impacted American democracy was through the concept of federalism. The Confederacy’s system of shared governance among the various nations provided a model for the federal structure of the United States. Here’s the thing: this wasn’t a theoretical exercise for the Iroquois. They had centuries of practical experience making it work.

Each tribe might have its own issues, but the Iroquois Confederacy is about unification through mutual defense and it conducts foreign affairs. Yet individual nations retained sovereignty over their internal matters. Does that sound familiar? It should, because just as the Iroquois nations retained individual sovereignty while participating in a collective decision-making process, the U.S. Constitution established a balance of power between state and federal governments.

Franklin referenced the Iroquois model as he presented his Plan of Union at the Albany Congress in 1754, attended by representatives of the Iroquois and the seven colonies. Benjamin Franklin wasn’t just making polite conversation with Native leaders. He was studying a working model of what the colonies desperately needed. The Iroquois had figured out how to preserve distinct identities while creating a unified front, something that would become absolutely essential to the survival of the American experiment.

Checks and Balances Before They Were Cool

You probably learned in school that checks and balances came from Enlightenment thinkers like Montesquieu. That’s partially true, but it’s not the whole story. Some of the constitutional articles most relevant to our current domestic affairs come from the confederacy, such as consciously separating responsibilities in government to ensure a balance of power; not allowing people to hold two offices across branches to avoid overpowering any particular individual; and ensuring a process for removing leaders from power for crimes and misdemeanors.

Let’s be real here. The Iroquois weren’t just theorizing about preventing tyranny. They were actually doing it. Leaders were held accountable for their decisions, and the community had the right to remove a sachem if they felt that the leader was not acting in the best interest of the people. This accountability mechanism was crucial in preventing the abuse of power and ensuring that leaders remained attuned to the needs and desires of their constituents.

Iroquois lawmakers didn’t go to war. Civilian and military rule was separate. This separation of military and civilian authority was revolutionary, especially considering that European models at the time typically concentrated both powers in the hands of royalty. The Founders borrowed this principle directly, creating a system where elected civilians maintain control over the military. It’s hard to overstate how radical this was for its time.

Representative Democracy With a Consensus Twist

At the heart of the Haudenosaunee system was the “Great Council,” a council composed of representatives from each member nation. These representatives, or sachems, deliberated and made decisions by striving for consensus, a concept that is a cornerstone of American democracy. The genius of this system wasn’t just that people had representation. It was how that representation functioned.

Each nation maintained its own leadership, but they all agreed that common causes would be decided in the Grand Council of Chiefs. The concept was based on peace and consensus rather than fighting. Now, the American system didn’t adopt pure consensus decision making, opting instead for majority rule in most cases. Still, the underlying principle of representation and deliberation came directly from observing how the Iroquois conducted their affairs.

Canasatego introduced the colonists to the federalist ideas that bound the disparate tribes into unity: it was a bond that encouraged unity, especially in matters of defense, even as it supported the independence of each tribe when it came to self-government. When Canasatego spoke at the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster, he wasn’t just making suggestions. He was demonstrating a living, breathing alternative to the fragmented colonial system. Franklin listened, and those ideas directly influenced his Albany Plan of Union and later constitutional thinking.

Symbols of Unity That Endure

Have you ever really looked at the Great Seal of the United States? That eagle clutching arrows isn’t random imagery. This inspired the bundle of 13 arrows held by an eagle in the Great Seal of the United States. The story behind this is actually quite moving.

Canassatego handed an arrow to Ben Franklin and asked him to break it. He was able to break it easily. He then handed Franklin six arrows. He was unable to break them. This simple demonstration conveyed a profound truth about the power of unity, and Franklin never forgot it.

The tradition is that the chiefs maintained the council fire and met to discuss confederacy issues beneath the tree; the eagle that flew over the tree guarded the confederacy looking out for enemies, and a bunch of five arrows, one representing each nation, were bound together, with the observation that it is much harder to break a bundle of five arrows than just one arrow. These weren’t just pretty symbols. They represented fundamental principles about collective strength and mutual protection. When the Founding Fathers designed the symbols of the new nation, they consciously borrowed from this Indigenous wisdom, creating visual reminders of unity that Americans still recognize today.

Women’s Political Power and Governance

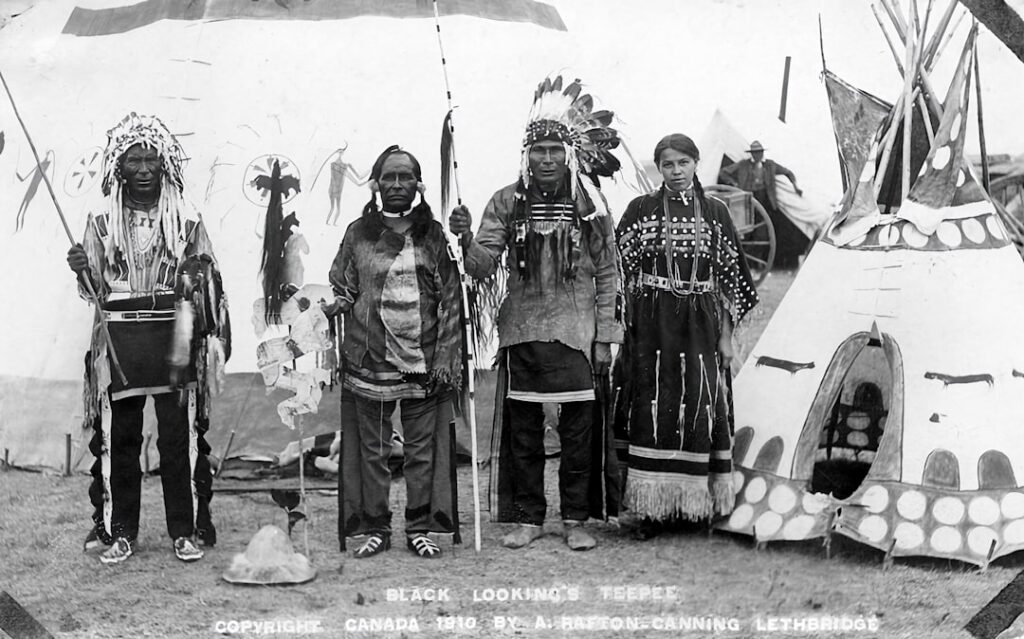

Here’s where things get really interesting, and honestly, where early America failed to follow the Iroquois example as fully as it should have. Haudenosaunee women controlled the economy in their nations through their responsibilities for growing and distributing the food. They had the final authority over land transfers and decisions about engaging in war. Let that sink in for a moment.

While Iroquois sachems were men, women nominated them for their leadership positions and made sure they fulfilled their responsibilities. Clan Mothers wielded enormous political influence. Clan mothers, the elder women of each clan, played a critical role in the political process by nominating sachems and having the authority to remove them if they failed to fulfill their responsibilities. This wasn’t symbolic power or influence exercised behind the scenes. This was direct, institutionalized political authority.

The contrast with colonial America couldn’t have been starker. At mid-nineteenth century, the majority of women living in the United States had no say in family or government decisions. It was illegal in every state for women to vote. They could not serve on a jury, sue or be sued, write a will or in any way act as a legal entity. Early feminists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage lived in close proximity to Iroquois communities and were deeply influenced by what they witnessed. There’s no doubt that the white women were extremely aware of the differences in women’s roles between the Iroquois and Americans and were strongly influenced by the political power and social status of the Iroquois women.

Long-Term Thinking and the Seventh Generation

The Native American model of governance that is fair and will always meet the needs of the seventh generation to come is taken from the Iroquois Confederacy. The seventh generation principle dictates that decisions that are made today should lead to sustainability for seven generations into the future. Now that’s what I call long term planning.

This principle represents perhaps the most profound difference between Iroquois governance and what the Founders ultimately created. Think about it: every decision made with the welfare of your great great great great great grandchildren in mind. The Great Law of Peace also emphasizes the importance of living in harmony with nature. It teaches that humans have a responsibility to protect the environment and ensure its sustainability for future generations. This principle, often referred to as the “Seventh Generation Principle,” urges leaders to consider the long term impact of their decisions on the natural world.

The American Constitution, brilliant as it is in many ways, lacks this explicit commitment to intergenerational justice and environmental stewardship. Imagine how different policy debates about climate change, national debt, or infrastructure might be if the seventh generation principle had been embedded in American constitutional thought from the beginning. This is one area where the students didn’t fully absorb the teachers’ wisdom, and we’re living with the consequences.

The Iroquoian system, expressed through its constitution, “The Great Law of Peace,” rested on assumptions foreign to the monarchies of Europe: it regarded leaders as servants of the people, rather than their masters, and made provisions for the leaders’ impeachment for errant behavior. This fundamental reconception of political authority, combined with practical mechanisms for accountability and participation, created a system that was genuinely of the people.

The influence wasn’t perfect, and the Founders certainly didn’t adopt everything the Iroquois had to offer. They ignored the role of women in governance, which set American democracy back by centuries. They failed to fully embrace the environmental consciousness and long term thinking that characterized Iroquois decision making. They created a more centralized system than the looser confederacy model. Yet the core insights about federalism, representation, checks and balances, and popular sovereignty found fertile ground in the minds of people like Franklin, Jefferson, and others who had direct exposure to Iroquois governance.

Colden was writing of a social and political system so old that the immigrant Europeans knew nothing of its origins – a federal union of five (and later six) Indian nations that had put into practice concepts of popular participation and natural rights that the European savants had thus far only theorized. The Iroquois weren’t theorizing. They were doing. And in doing, they provided a practical demonstration that democracy could work on a large scale, uniting diverse peoples while preserving their distinct identities.

When you vote, when you see the separation of powers in action, when you witness the balance between state and federal authority, you’re experiencing the legacy of Indigenous political innovation. The next time you hold a dollar bill and look at that eagle clutching thirteen arrows, remember where that image really came from. Remember the Haudenosaunee and their Great Law of Peace. Democracy in America has many roots, some crossing the Atlantic from Europe and others growing right here in this soil for centuries before any European ships arrived.

What do you think might be different today if the Founders had more fully embraced all aspects of Iroquois governance, including the political power of women and the seventh generation principle? The conversation about Indigenous contributions to American democracy is far from over.