When water rises fast enough to move houses, you don’t forget the sound – it’s a low, steady roar that turns streets into rivers and dunes into memory. Along North Carolina’s slender line of barrier islands, storm surge has been the sculptor-in-chief, carving new inlets, shoving sand miles inland, and rewriting maps in a single tide. Scientists now treat these watery bulldozers as both disaster and data point, decoding what each surge says about wind, pressure, and the hidden contours of the seafloor. The mystery isn’t whether the coastline will change; it’s how, where, and how often – and whether we learn fast enough to keep people safe while letting the coast breathe. The story of eleven defining surges is really a story about a living shoreline, a restless ocean, and our stubborn decision to build right at their boundary.

The Hidden Clues

Walk a storm-tossed beach on Hatteras or Ocracoke and you can spot the clues if you know where to look: fresh overwash fans glittering with shell hash, dune scarps cut clean like slices in cake, and wrack lines snagged high in live oaks where water doesn’t belong. Those are the fingerprints of surge, the temporary ocean that climbs over the island and deposits the island, grain by grain, farther landward. In peat cores, researchers find salt-tolerant microfossils suddenly appearing above freshwater layers – quiet, microscopic witnesses to ancient floods. Even the roads tell the story; long, straight sections of NC 12 kink and crumple where waves pushed sand across asphalt, insisting the island wants to migrate. Surge leaves a narrative as clear as any headline: this coast moves, and it prefers to move on storm time, not ours.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Not so long ago, coastal observers tracked storm tides with painted posts on docks and pencil marks on store walls – honest, but hard to compare. Today, a web of NOAA tide gauges, USGS rapid-response sensors, and university field arrays records water level and wave energy in real time, turning chaos into datasets. Piloted drones sweep freshly cut inlets at low tide, while lidar-equipped aircraft map dune heights down to the inch before and after landfall. High-resolution numerical models – think ADCIRC and its cousins – digest wind fields, barometric pressure, and bathymetry to forecast where water will pile up in twisted estuaries like the Neuse and Pamlico. When the model matches the sensor and the satellite, scientists gain confidence not just in what happened, but in what is likely to happen the next time the barometer dives.

Eleven Surges in Focus

Some surges are folklore because they re-wrote geography: the 1933 Outer Banks hurricane scoured the islands; the 1944 Great Atlantic hurricane ate dunes built by a generation of hands. Hurricane Hazel in 1954 brought ocean water hurling into Brunswick beaches, a benchmark many old-timers still use. Donna in 1960 hammered Cape Hatteras with a long fetch that stacked water like wind-stressed cordwood. Fran in 1996 pushed the ocean deep into the lower Cape Fear, and Floyd in 1999 added river floods that collided with elevated tides across the low country. Isabel in 2003 famously cut a new inlet on Hatteras, Irene in 2011 heaved Pamlico Sound waters back onto the islands, Florence in 2018 swamped New Bern from the Neuse, Dorian in 2019 drowned Ocracoke’s streets with sound-side rise, and Ophelia in 2023 reminded everyone that quick-forming coastal storms don’t need major-category winds to push dangerous water into homes and harbors.

The Science Behind the Walls of Water

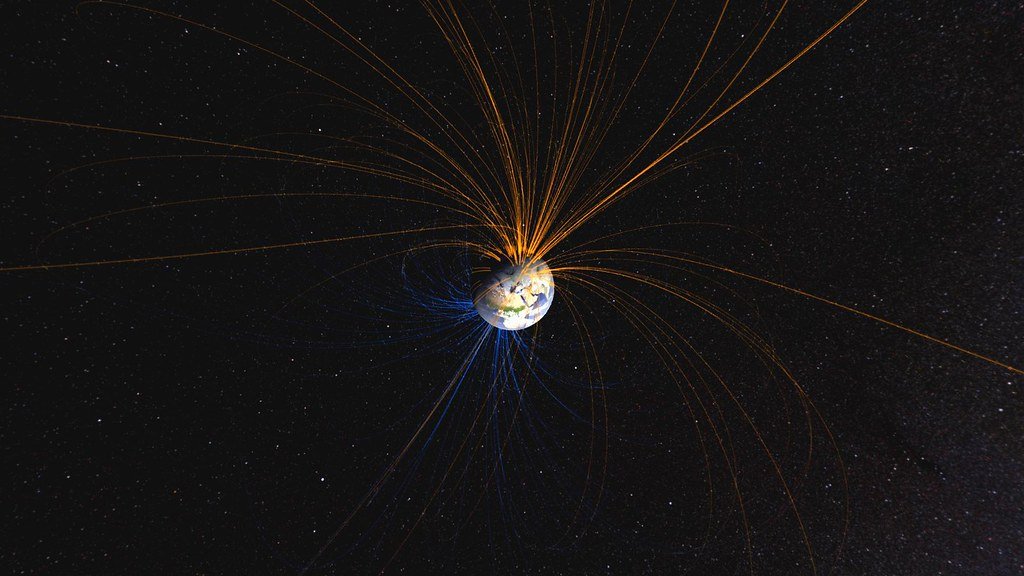

Storm surge isn’t a single phenomenon but a messy duet between the atmosphere and the sea: wind stress shoves water toward shore, while low pressure lets the surface dome upward, and the continental shelf decides how much of that momentum becomes height. North Carolina adds a twist with its broad, shallow sounds; water driven through Oregon or Hatteras inlets can slosh across Pamlico like soup in a tilted bowl, then rush back when the wind shifts. That’s why “sound-side” flooding can arrive hours after the eye passes, catching people off guard even as skies clear. Bathymetry magnifies or muffles the rise – subtle channels, shoals, and capes steer energy into neighborhoods the way a horn funnels sound. Add rainfall and river discharge, and you get compound flooding, where surge blocks drainage just as runoff peaks, a one-two punch that turns a bad day into a generational disaster.

Why It Matters

Storm surge is the leading cause of hurricane-related loss of life and property, and along the Tar Heel coast it also determines the shape of the islands we love to visit. Every new inlet and overwash sheet is a reminder that barrier islands are not walls but conveyor belts of sand, designed by nature to roll landward with rising seas. That dynamic clashes with fixed infrastructure – sewer lines, power poles, and oceanfront roads – that assumes the ground beneath will stay put. For fisheries, surge can salt farm fields and fresh marshes alike, changing nursery habitat for shrimp and crabs for months after the storm. And for towns tied to tourism, a single surge can erase a summer’s revenue, with small businesses taking the brunt long after the headlines fade. Consider these grounding facts that shape planning debates: – Most hurricane damages typically come from water, not wind, making flood risk communication central to preparedness. – Barrier islands are inherently mobile landforms; attempts to freeze them often shift, rather than solve, risk. – Relative sea level is rising along much of the North Carolina coast, nudging baseline tides higher and giving surge a head start.

Global Perspectives

North Carolina’s experience resonates with coastlines worldwide that juggle storm risk and coastal identity. The Netherlands answers with massive gates and layered defenses; the Philippines faces fast-rising waters with evacuation culture and community networks; Bangladesh has invested in shelters and early warnings that turn forecasts into survival. Each place teaches a slightly different lesson: some lean on engineering, others on social systems, a few on strategic retreat and restoration. On a barrier island, though, the physics rule – soft solutions like living shorelines, dune restoration, and marsh migration often stand the best chance of keeping up with motion. The trick is humility: letting the coast do some of its natural work while making space for people to stay safe and economies to adapt.

The Future Landscape

As seas creep upward and the ocean heats, scientists expect the strongest storms to carry more moisture and, in many basins, to blow harder, setting the stage for higher surges on slightly higher baselines. Forecast tools are meeting the moment: ensembles now generate street-scale inundation maps hours before landfall, and digital twins of communities let planners test “what if” scenarios long before concrete is poured. Sensors have gotten tougher and cheaper, so temporary networks can be stapled to bridges and pilings ahead of a storm, then yanked out with a trove of data when the sky clears. Policy is shifting too, from elevating homes and critical equipment to moving infrastructure off the most mobile parts of the islands and treating roads like flexible, sacrificial features. It’s not defeat to give sand room to roam; it’s strategy, and it’s likely the only path that keeps a working coastline working.

Conclusion

Start by knowing your personal flood pathways – river, sound, or ocean – and check your local inundation maps before hurricane season, not during it. If you live or vacation on the barrier islands, plan an evacuation route that doesn’t depend on a single bridge and pack for days, not hours. Support projects that restore dunes and marshes, because those living edges blunt surge without the hard rebounds that seawalls can trigger. Consider elevating utilities and installing flood vents, and talk to your neighbors about recovery plans so no one rides out a surge alone. Finally, back the scientists: community monitoring programs and local universities depend on volunteers, data, and steady funding to make the next forecast just a bit smarter than the last.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.