When we think about emotions, we typically imagine them as uniquely human experiences. Yet across the animal kingdom, from the smallest mouse to the largest whale, creatures display complex emotional behaviors that challenge our understanding of what it means to feel. Recent surveys of animal behavior researchers show that an overwhelming majority ascribe emotions to a broad range of species, including non-human primates, mammals, birds, and even cephalopods. This marks a dramatic shift from 20th-century attitudes when the importance of emotions in animals’ lives was largely ignored or denied. Today’s scientific evidence reveals that nature has developed its own sophisticated science of emotions, one that operates across species boundaries and serves crucial survival functions. Let’s explore eleven remarkable behaviors that demonstrate just how emotionally rich the animal world truly is.

Elephants Practice Ancient Funeral Rituals

When a beloved member of an elephant troop dies, those left behind will mourn the lost individual by “burying” the body with leaves and grass, and showing continued interest in the deceased. Just as humans visit the gravesites of their lost loved ones, elephants visit the bones of dead elephants for years to come. They have been observed investigating the bones of deceased elephants, displaying particular interest in skulls and tusks. They also exhibit behaviors like attempting to revive deceased individuals, staying with the body, and showing clear signs of distress around death. These observations suggest a deep understanding of death and loss. An elephant’s ability to feel deep empathy is hugely evident in how they grieve and mourn their dead. The experience of loss for an elephant, whether through forced separation or death, significantly impacts them. Evidence highlights the distress this causes. For instance, a six-month-old African calf was seen nuzzling her mother’s carcass, wandering around confused, and returning to the carcass. Tragically, the calf was presumed dead within three months.

Dolphins Carry Their Grief Through Ocean Depths

Female bottlenose dolphins have been observed carrying dead calves – presumably their babies – on their back for days or even weeks. Observers infer it’s an expression of maternal grief. On one occasion, the mom was accompanied by four other dolphins – perhaps family members who were providing emotional support. Cetaceans, including dolphins and whales, are known for their complex social structures and communication skills. Instances have been documented where dolphins carry their dead calves for days, seemingly reluctant to let them go. Whales, too, have been observed displaying similar behaviors. These actions are difficult to interpret as anything other than mourning or grieving. The sheer number of neurons underscores their capacity for learning and memory, while a well-developed limbic system suggests they experience a range of emotions, including empathy, grief, and joy. Cetaceans exhibit rich emotional lives, showcasing feelings such as joy, grief, and empathy. Documented instances of cetaceans “mourning” deceased companions indicate a profound emotional connection and an understanding of loss.

Rats Choose Compassion Over Chocolate

Interestingly enough, while rats are commonly considered ugly and disgusting, in experiments a rat will show compassion by coming to the aid of a fellow rat in distress, even when it means having to share a treasured piece of chocolate. Not all humans demonstrate this trait. Those seemingly filthy creatures scampering in the sludge of subway stations or trashcans, rats have empathy for each other. In experiments conducted in the late 1950s and early 1960s, hungry rats that were only fed if they pulled a lever to shock their littermates refused to do so, suggesting that the rodents have a sense of empathy and compassion for their fellows. We know that fish are conscious and sentient, rats, mice and chickens display empathy and feel not only their own pain but also that of other individuals. Beyond such anecdotal evidence, support for empathetic reactions has come from experimental studies of rhesus macaques. Macaques refused to pull a chain that delivered food to themselves if doing so also caused a companion to receive an electric shock. This inhibition of hurting another conspecific was more pronounced between familiar than unfamiliar macaques, a finding similar to that of empathy in humans.

Ravens Hold Vigils for Their Fallen Friends

One magpie had obviously been hit by a car and was laying dead on the side of the road. The four other magpies were standing around him. One approached the corpse, gently pecked at it-just as an elephant noses the carcass of another elephant- and stepped back. Another magpie did the same thing. Next, one of the magpies flew off, brought back some grass, and laid it by the corpse. Another magpie did the same. Then, all four magpies stood vigil for a few seconds and one by one flew off. Magpies are corvids, a very intelligent family of birds. Once disregarded in the world of animal intelligence studies, many crow and raven species are now ranked near primates in terms of cognitive abilities. Wildlife experts John Marzluff and Tony Angell expose crow intelligence in their 2012 book, Gifts of the Crows, writing “Corvids assume characteristics that were once ascribed only to humans, including self-recognition, insight, revenge, tool use, mental time travel, deceit, murder, language, play, calculated risk taking, social learning, and traditions. Ravens seem to respond to the emotional states of other ravens.

Chimpanzees Experience the Full Spectrum of Human-Like Emotions

Chimpanzees laugh when they play and cry when they grieve. They experience and express joy, anger, jealousy, compassion, despair, affection, and a host of other emotions. Touching and grooming are vital to maintaining stable relationships and keeping the peace within the community group. Their rich and complex emotional repertoire matches the complexity of their intellect. Chimpanzees use feelings as yet another way to navigate through their lives and relationships. Their reactions range from anger to exhilaration, from humor to despondence – and every other emotion we know. Primates, in particular non-human great apes, are candidates for being able to experience empathy and theory of mind. Great apes have complex social systems; young apes and their mothers have strong bonds of attachment and when a baby chimpanzee or gorilla dies, the mother will commonly carry the body around for several days. Jane Goodall has described chimpanzees as exhibiting mournful behavior. Koko, a gorilla trained to use sign language, was reported to have expressed vocalizations indicating sadness after the death of her pet cat, All Ball.

Dolphins Rescue Strangers Across Species Lines

Dolphins routinely show love for species not their own. Several dolphins have practiced random acts of kindness by rescuing swimmers from hammerhead sharks. A few generous dolphins have even guided stranded whales back to sea. But the cetaceans save most of their goodwill for others in their pod – just like humans, they have a you-scratch-my-nose, I’ll-scratch-yours ethic that demands routine kindness and generosity. On a beach in New Zealand, a dolphin came to the rescue of two pygmy sperm whales stranded behind a sand bar. After people tried in vain to get the whales into deeper water, the dolphin appeared and the two whales followed it back into the ocean. Reports of dolphins aiding injured individuals and even other species, including humans, illustrate their capacity for empathy and altruism. Animals display empathy toward humans and other animals in a multitude of ways, including comforting, grieving and even rescuing each other from harm at their own expense. Empathy in animals spans species and continents. Dolphins, known for their playful behavior, reinforce social bonds through their interactions.

Whales and Orcas Demonstrate Deep Family Bonds

Asha de Vos, a Sri Lankan marine biologist and National Geographic Explorer, notes that pilot whales live in family pods. “Mourning is a reflection of the strong social bonds that are formed through their lifetimes,” she says. As inherently social animals, cetaceans form intricate groups known as pods, with complex hierarchies and relationships. For instance, orcas often have family structures led by older females. These matriarchal structures help pods survive and thrive, particularly in orcas that hunt cooperatively. What happens when whalers harpoon the largest of the pod, which in baleen whales tends to be females? Not only are the whalers killing one of the most important members, often with experiences and knowledge critical to the survival of the pod, but the remaining members of the whale family left behind mourn the loss(es) acutely. In some species, such as elephants and orcas, the elders share knowledge gained from experience with the younger ones.

Prairie Dogs Have Complex Warning Languages

While not directly covered in the search results, prairie dogs represent one of nature’s most sophisticated communication systems. Most respondents ascribed emotions to at least some members of each taxonomic group of animals considered, including insects and other invertebrates. A majority of survey respondents ascribed emotions to “most” or “all or nearly all” non-human primates, other mammals, birds, octopus, squids and cuttlefish, and fish. These small mammals use different calls to warn about specific predators, demonstrating not just survival instincts but emotional responses to danger that benefit their entire community. Bats, dolphins, whales, frogs, and various rodents use high-frequency sounds to find food, communicate with others, and navigate. Many animals also display wide-ranging emotions, including joy, happiness, empathy, compassion, grief, and even resentment and embarrassment. The complexity of prairie dog communication suggests emotional investment in community welfare that goes beyond simple alarm calls.

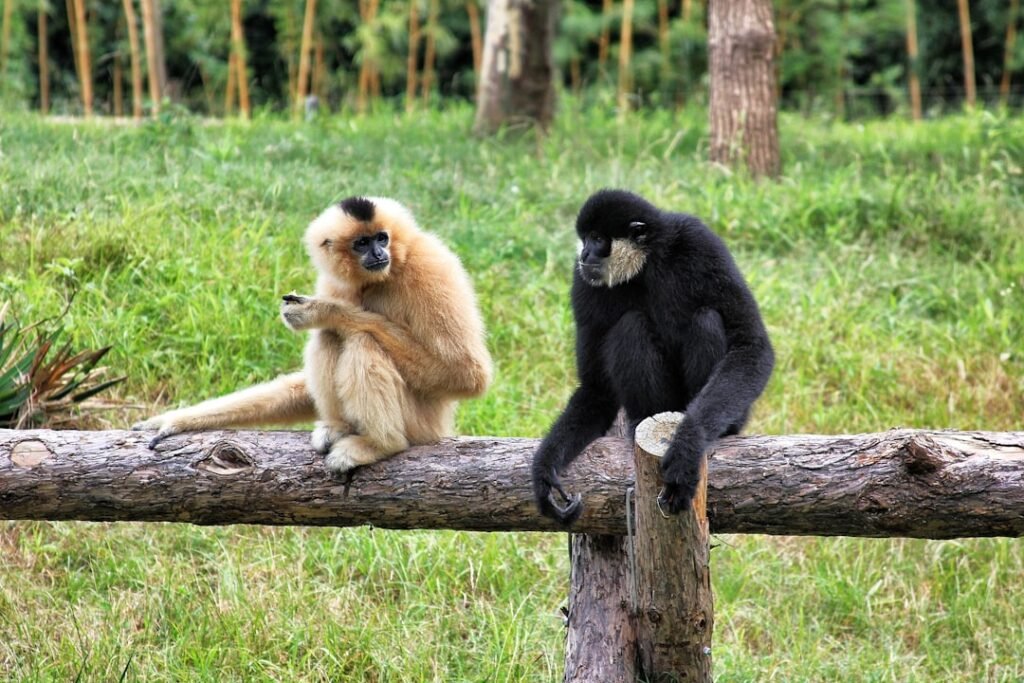

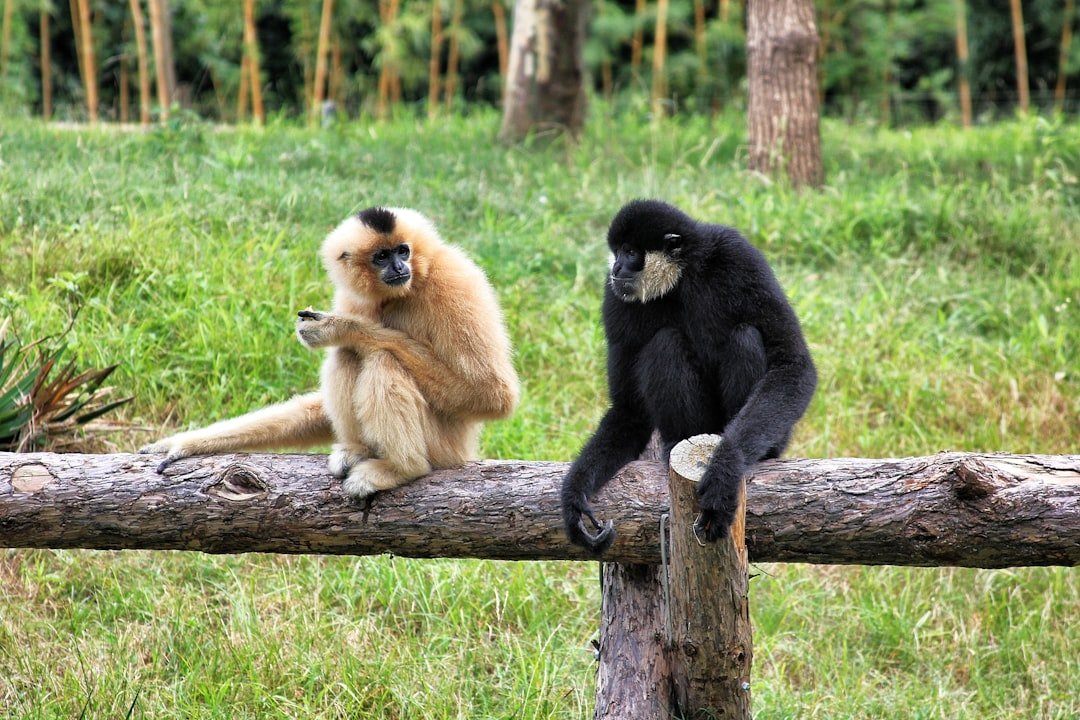

Primates Display Sophisticated Social Justice

Many primates, such as chimpanzees and bonobos, exemplify social intelligence. They engage in intricate social interactions, displaying empathy, cooperation, and even deception. For instance, chimpanzees often form alliances and can manipulate social dynamics to their advantage. Baboons are known for their complex social structures and hierarchies. These primates live in large troops, where relationships and ranks play crucial roles in daily life. Their intelligence is evident in their ability to navigate social dynamics, form alliances, and resolve conflicts. Rats show kindness, orcas mourn their dead, and monkeys protest injustice. The concept of fairness appears deeply embedded in primate social systems, with individuals showing emotional responses to perceived inequities. This type of emotional awareness functions to coordinate activity among group members, facilitate social cohesion and motivate conciliatory tendencies, and is likely to play a key role in coordinating social behaviors in large-brained social primates. There is evidence in the animal world for contagious yawning, scratching and emotional behavior, including play and aggression.

Dogs Display Remarkable Emotional Intelligence

Dogs presented with images of either human or dog faces with different emotional states paired with vocalizations from the same individual with either positive or negative emotional state look longer at the face whose expression is congruent to the emotional state of the vocalization, for both other dogs and humans. This is an ability previously known only in humans. According to an article in the New York Times, Iraq veteran Benjamin Stepp returned home from two deployments with a traumatic brain injury and multiple other injuries causing pain. During a lecture at graduate school, Stepp tried hard to focus, but he was agitated. No one in the class noticed except for his service dog Arleigh, who jumped into his lap to comfort him. He believed Arleigh always empathized when he was struggling emotionally. Comfort dogs also display empathy. When the horrific events of 2012 happened at Sandy Hook Elementary School, comfort dogs were able to help children open up and heal. Some children spoke directly to the dogs about what they’d experienced. In fact, one child spoke for the first time since the shootings after petting one of the dogs. Five consistent and stable “narrow traits” were identified in dogs, described as playfulness, curiosity/fearlessness, chase-proneness, sociability and aggressiveness. A further higher order axis for shyness–boldness was also identified.

Play Behavior Reveals Pure Animal Joy

The unmistakable emotions associated with play – joy and happiness – drive animals to become at one with the activity. One way to get animals (including humans) to do something is to make it fun, and there is no doubt that animals enjoy playing. Studies of the chemistry of play support the claim that play is fun. Dopamine (and perhaps serotonin and norepinephrine) are important in the regulation of play. Rats show an increase in dopamine activity when anticipating the opportunity to play, and they enjoy being playfully tickled. Watching young animals at play – puppies tumbling, ravens sliding down snowy roofs, dolphins leaping in synchrony – leaves little doubt that many species experience something akin to happiness. Play behavior, studied extensively by neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp, activates brain reward systems. In rats, rough-and-tumble play triggers high-pitched chirps, a sound interpreted as laughter. Blocking dopamine reduces this joyful vocalization, while stimulating play circuits restores it. This demonstrates that joy is neurologically ingrained, not merely human projection. Reiss and others have since observed dolphins in aquariums make rings and toy with them in myriad ways. In the wild, dolphins play chase with one another. They’re just one of many species – in addition to dogs and cats, as everyone knows – that engage in play.

A New Understanding of Our Shared Emotional World

The evidence is overwhelming: animals experience rich emotional lives that parallel our own in remarkable ways. The inner processes of many animals are as complex as those of humans. The difference is that we can express them in language; we can talk about our feelings. It’s likely that numerous species feel their way through life because, as Charles Darwin asserted, differences between species are a matter of degree, not kind. Non-human animals are individuals with personalities. Other animals may be more aware of feelings than we are, feel them more intensely, or experience different shades of feeling than we do. Other creatures might well have stronger, more immediate feelings because, unlike us, they don’t appear to ruminate or analyze. This growing understanding challenges us to reconsider our relationship with the natural world and recognize that emotional complexity isn’t uniquely human – it’s one of nature’s most fundamental features. What do you think about these remarkable displays of animal emotions? Do they change how you view our fellow creatures on this planet? Tell us in the comments.

Hi, I’m Andrew, and I come from India. Experienced content specialist with a passion for writing. My forte includes health and wellness, Travel, Animals, and Nature. A nature nomad, I am obsessed with mountains and love high-altitude trekking. I have been on several Himalayan treks in India including the Everest Base Camp in Nepal, a profound experience.