You might think you know Earth pretty well. Yet here’s a startling truth. Roughly 95 percent of the ocean remains unexplored, much of it hidden in the deep sea. While we beam back crystal clear images from Mars, the ocean floor right beneath us holds secrets that continue to baffle the brightest minds in marine science.

The deep ocean is a place of extremes. Total darkness. Crushing pressure. Temperatures near freezing. Still, life has found ways not just to survive but to thrive down there. Let’s explore the mysteries that scientists are racing to understand, from glowing creatures to ancient ecosystems fueled by chemicals instead of sunlight.

Hydrothermal Vents: Underwater Chimneys of Life

In 1977, scientists exploring an oceanic spreading ridge near the Galápagos Islands made a stunning discovery: openings in the Pacific Ocean seafloor with warm, chemical-rich fluids flowing out, later revealing previously unknown organisms and entire ecosystems around the vents, thriving in the absence of sunlight. These hydrothermal vents revolutionized our understanding of where life can exist. The fluid temperatures can reach 400°C or more, yet they don’t boil due to the crushing deep-sea pressure.

What makes these vents truly remarkable is the ecosystem they support. Hydrothermal vent zones have a density of organisms 10,000 to 100,000 times greater than the surrounding seafloor. The food chain at these ocean oases relies on chemosynthesis, carried out by bacteria, similar to photosynthesis used by plants on land, but instead of using light energy from the Sun, the bacteria use chemicals drawn from the vent fluid. Scientists continue exploring these extreme environments, with discoveries in 2022 on the Knipovich Ridge off the coast of Svalbard, and in 2024, five new hydrothermal vents announced in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean.

The Mariana Trench: Earth’s Deepest Mystery

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about 200 kilometres east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deepest oceanic trench on Earth, with the maximum known depth being 10,984 metres at the Challenger Deep. Let’s be real, that’s deeper than Mount Everest is tall. The pressure down there is mind-boggling. At the bottom of the trench at around 11,000 metres below the sea surface, the water column exerts a pressure of 1,086 bar, approximately 1,071.8 times the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level.

For decades, scientists assumed very little could survive in such hostile conditions. Recent expeditions have shattered that assumption. During the TS21 expedition researchers collected 1,648 sediment samples across 6,000 to 10,900 meters in the Mariana Trench, revealing an unprecedented level of taxonomic novelty, with 89.4% of identified microbial species previously unreported. The expedition set many new records, such as the deepest rock samples ever collected, and new species, including the deepest fish ever recorded. Even at nearly seven miles down, the trench teems with life we’re only beginning to understand.

Chemosynthetic Ecosystems in Hadal Zones

The hadal zone represents the deepest oceanic regions, beyond 6,000 meters. Here’s the thing about these places: they’re completely cut off from sunlight. At the bottom of the Kuril–Kamchatka Trench northeast of Japan, a team discovered the deepest-known ecosystem with animals on the planet during dives in 2024. These communities survive on an unusual energy source.

The ecosystem discovered relies on an unusual source of energy, deriving energy from methane, hydrogen sulfide and other compounds dissolved in fluids that seep from below the seafloor. Scientists exploring two oceanic trenches in the northwest Pacific discovered thriving communities of marine life nearly six miles beneath the surface, making it the deepest colony of creatures ever observed, dominated by tube worms and clams able to survive through chemosynthesis, meaning life here is nourished by fluids rich in hydrogen sulfide and methane seeping from the seafloor. This year, expeditions to another trench in the southern Pacific Ocean found similar ecosystems, offering strong evidence that there is a global corridor of chemosynthetic ecosystems across Earth’s oceans.

Bioluminescent Creatures: Nature’s Light Show

Nearly 90% of marine creatures dwelling below 1,500 feet produce their own biological light through bioluminescence. Think about that. In the pitch-black depths, most animals have evolved to create their own illumination. In the deep sea, bioluminescence is extremely common, and because the deep sea is so vast, bioluminescence may be the most common form of communication on the planet.

The chemistry behind this glow is fascinating. Bioluminescence occurs through a chemical reaction that produces light energy within an organism’s body, requiring luciferin, a molecule that, when it reacts with oxygen, produces light. Most of the bioluminescence produced in the ocean is in the form of blue-green light because these colors are shorter wavelengths of light, which can travel through and thus be seen in both shallow and deep water. Creatures use this ability in clever ways. Some attract prey with glowing lures. Others flash brilliant displays to startle predators, while certain species use lights on their undersides to break up their silhouette when viewed from below.

The Twilight Zone: An Unexplored Middle Layer

Between the sunlit surface and the pitch-black abyss lies the ocean’s twilight zone, also called the mesopelagic zone. Scientists who dare to explore these depths risk their lives for discovery. Divers like Luiz Rocha and Mauritius Bell gear up to head 330 feet below the surface, far beyond the reach of most scuba divers, in the mesophotic or upper twilight zone where sunlight is scarce and mysteries abound.

Scientists once thought that the deeper one dove, the drabber and more lifeless a reef would become, but over the past few decades, they’ve learned that reefs in the twilight zone are wildly biodiverse and harbor colorful creatures, though our knowledge of deep reefs is still in its infancy and most places still have not been explored. The challenge with studying this zone is its inaccessibility. It’s too deep for regular scuba divers yet not quite deep enough to justify expensive submersibles for every expedition. Most mesophotic reefs in the twilight zone remain unexplored and, as a result, unprotected.

Abyssal Plains: The Hidden Seafloor Desert

Imagine vast, flat expanses stretching for thousands of miles in complete darkness. That’s the abyssal plain, covering more of Earth’s surface than all our continents combined. Only a minuscule fraction of the deep seafloor has been imaged, according to a groundbreaking study published in Science Advances. I know it sounds crazy, but we’ve mapped more of Mars than our own ocean floor.

Extensive mapping of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone at 4,000 m depth identified 788 deep-sea species, many previously undescribed, though mining tests reduced animal abundance by 37% and species diversity by 32% in affected areas. The abyssal plains aren’t empty wastelands. Recent research has discovered that even in these remote, food-scarce environments, microbial communities thrive in the sediment. Plants form the basis of all food webs and in the ocean those plants are phytoplankton living only in surface waters, but detritus produced in surface waters drifts down to the depths as marine snow, which is a major food source for many invertebrates.

Seamounts and Underwater Mountains

Rising from the ocean floor like skyscrapers in an underwater city, seamounts are underwater mountains formed by volcanic activity. Carter is one of thousands of seamounts formed from extinct, underwater volcanoes, most remaining unstudied. These geological features create unique habitats that concentrate marine life in otherwise barren areas.

Vogt Seamount hosted the most diverse and dense community of deep-sea coral and sponges of the entire cruise, with this seamount featuring over 12 individual colonies in single images, some of which were quite large. The currents swirling around seamounts bring nutrient-rich water upward, creating oases of biodiversity. Scientists have discovered new species on nearly every seamount they explore, suggesting thousands more remain hidden. New high-density communities were documented at Vogt Seamount, Maug, Explorer Ridge, and Farallon De Medinilla, confirming the presence of precious corals in the northern portion of the Monument and expanding the known depth range for bamboo corals by approximately 100 meters.

Cold Seeps and Methane Vents

While hydrothermal vents spew superheated water, cold seeps release methane and other hydrocarbon-rich fluids at near-freezing temperatures. Methane and hydrogen escape through cracks in the ocean floor, creating ephemeral landscapes that support an ecosystem adapted to survive on chemosynthetic reactions. These seeps can persist for centuries, creating stable environments for specialized communities.

The organisms living around cold seeps are equally bizarre as those at hydrothermal vents. Tubeworms, clams, and mussels form dense colonies, all relying on symbiotic bacteria that convert methane into usable energy. Two powerful currents converge in the Mar del Plata Submarine Canyon in Argentina’s Exclusive Economic Zone, supporting incredible submarine canyon ecosystems that have not yet been observed by scientists. These methane seeps might be far more widespread than previously thought, with new discoveries happening regularly as exploration technology improves.

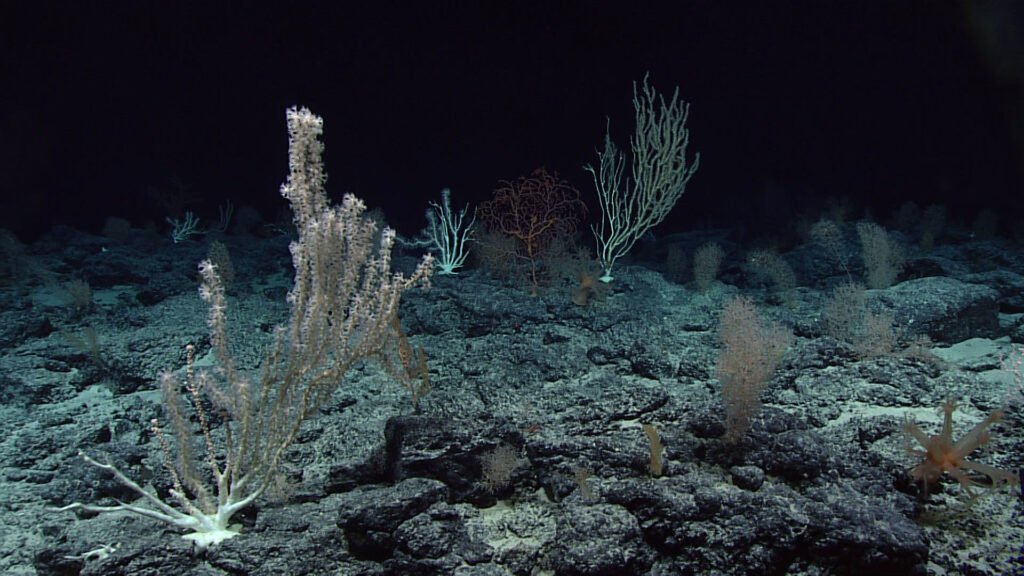

Coral and Sponge Gardens of the Deep

Gorgeous undersea gardens filled with bioluminescent corals are magical places that took more than 1,000 years to grow, yet we’re wiping them out with one bottom trawl for one haul of shrimp, and those ecosystems will never sustain life again in our lifetimes or many lifetimes into the future. Let me be honest, this one hits hard. Deep-sea corals grow incredibly slowly, sometimes adding only millimeters per year.

One of the priorities identified for the entire expedition was to survey deep-sea coral and sponge habitats, with this expedition being the first ever to specifically focus on identifying and documenting these habitats in the deep waters of the Marianas. Unlike their shallow-water cousins that depend on sunlight-loving algae, deep-sea corals filter feed on marine snow drifting down from above. When an iceberg the size of Chicago broke away from an Antarctic ice shelf, what they found was a vibrant and alienlike ecosystem of anemones, sea spiders, icefish and octopuses, including some new species, that had been living there for decades or even hundreds of years.

Unexplored Trenches and Submarine Canyons

As of January 2025, only 38% of Alaska’s seafloor has been mapped, and even less has been explored, with much of the deep Aleutian Arc virtually unknown, though research teams are working to explore and provide initial characterization of high-priority sites. Submarine canyons carve through continental shelves like underwater Grand Canyons, funneling nutrients and sediment from shallow waters to the abyss.

On a mission to explore methane seeps off the coast of Chile, Schmidt researchers also explored several submarine canyons where they snapped dramatic photos of anglerfish, with these canyons carved by strong currents that funnel sediments, nutrients and organisms through the system. These geological features create highways for deep-sea life, concentrating biodiversity in ways scientists are only beginning to understand. Researchers recently unveiled 14 new species from ocean depths exceeding 6,000 meters, with their findings including a record-setting mollusk, a carnivorous bivalve, and a popcorn-like parasitic isopod.

Conclusion: The Final Frontier Beneath the Waves

The ocean floor remains one of the last truly wild places on our planet. Every expedition brings discoveries that challenge what we thought we knew about life, adaptation, and the limits of survival. From glowing jellies drifting in the twilight zone to bizarre worms thriving on toxic chemicals at hydrothermal vents, the deep sea continues to astound us.

Research on deep-sea ecosystems is only a few decades old, and the technology for new discoveries is improving, but it’s important for different countries and scientific disciplines to collaborate on future efforts through initiatives like the Global Hadal Exploration Program, which is co-led by UNESCO and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The race is on to document these ecosystems before human activities like deep-sea mining potentially destroy places we haven’t even discovered yet. What other wonders are waiting in the darkness, just beyond the reach of our current technology? That question keeps ocean scientists awake at night, and honestly, it should fascinate all of us.