If you think American forests are just oaks, pines, and maples, you’re in for a shock. Scattered across the United States are tree species so unusual, so rare, or so ancient that they feel like something out of a different planet rather than your own backyard. Many of them live in tiny pockets of habitat, clinging to cliffs, swamps, or high mountain slopes where most people never go.

These are the trees that rarely make it into coffee-table books but quietly shape ecosystems, local cultures, and even scientific research. Once you meet them, it’s hard not to feel a bit protective, maybe even a little proud. As you read through this list, you might find yourself wondering how many more secret giants and botanical oddities are still hiding in the corners of the American landscape.

1. Franklin Tree (Franklinia alatamaha) – The Ghost of Georgia’s Forests

The Franklin tree is a botanical ghost, because no one has seen it growing wild since the early eighteen hundreds. It was discovered along Georgia’s Altamaha River in the seventeen hundreds, collected for gardens, and then quietly vanished from its natural habitat. Every Franklin tree alive today comes from those early garden specimens, making it a kind of living heirloom more than a truly wild species.

What makes it special is not just its sad story, but its beauty and mystery. It produces large white flowers with sunny yellow centers that look like something you’d expect in a tropical garden rather than in the American Southeast. No one is completely sure why it disappeared from the wild, though habitat loss and disease are leading suspects, which turns every surviving Franklin tree into a reminder of how quickly a species can slip away. Planting one is like planting a piece of American natural history in your yard.

2. Torreya (Florida Torreya) – The Most Endangered Tree You’ve Never Met

Hidden in the ravines along the Apalachicola River in Florida and southern Georgia, the Florida torreya is hanging on by a thread. This small conifer is one of the most endangered tree species in North America, with very few mature trees left in the wild. A fungal disease has been hammering it for decades, so most wild individuals are stunted, repeatedly dying back and resprouting rather than growing into tall, stately trees.

What’s remarkable is the passionate, sometimes controversial, grassroots effort to save it. Volunteers have been planting torreyas in places well outside their native range, hoping to give the tree a fighting chance in cooler, less disease-prone climates. The species itself is intriguing, with sharp, dark green needles and a deep evolutionary history that goes back millions of years. It’s like a living relic from a much older, wilder version of the eastern United States, one that we’re dangerously close to losing.

3. Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera) – The Hedge Tree With a Hidden Past

If you’ve ever seen a bumpy, chartreuse-green “brain fruit” on the ground in the Midwest or South, you’ve met the Osage orange. The tree’s oversized, knobbly fruits look almost comical, and animals today mostly ignore them, which has led scientists to suspect that they evolved to be eaten by giant Ice Age mammals that are now long gone. In other words, this is a tree whose original seed dispersers are extinct, and it’s still standing here, a little confused and out of place.

Historically, Indigenous peoples like the Osage valued the wood so highly for making bows that it was traded across long distances. The wood is incredibly strong, naturally rot-resistant, and burns hot, making it a kind of multi-tool tree before hardware stores existed. In the nineteenth century, farmers planted Osage orange closely in rows as living fences before barbed wire came along. It’s special because it quietly connects deep evolutionary time, Indigenous ingenuity, and the story of American farming in one thorny, neon-green package.

4. Kentucky Coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus) – The Frontier “Coffee” That Wasn’t

The Kentucky coffeetree looks a bit awkward at first glance, with thick, bare branches in winter that give it a rugged, skeletal look. In summer, it bursts into life with enormous compound leaves that cast a dappled shade unlike most other trees. Its large, hard pods once earned it a reputation on the frontier, where early European settlers roasted the seeds as a rough coffee substitute when actual coffee beans were hard to come by.

The seeds, however, are naturally toxic if not processed correctly, which makes its use for drinks more of a survival workaround than a culinary recommendation. Some scientists think, like the Osage orange, this tree originally relied on now-extinct large mammals to spread its seeds. Today, it’s valued as a tough urban tree that can handle pollution, poor soils, and city heat better than many common species. In a way, the Kentucky coffeetree has reinvented itself, moving from frontier kitchens to city streets without losing its oddball charm.

5. American Chinkapin (Castanea pumila) – The Little Chestnut With a Big Story

Most people have heard of the American chestnut, the once-mighty tree nearly wiped out by blight in the twentieth century. Fewer know its scrappy little cousin, the American chinkapin, which grows as a small tree or even a large shrub across parts of the Southeast. Instead of huge burs holding several nuts, chinkapins carry small, spiky burs with just a single, sweet nut inside, beloved by wildlife and, historically, by people too.

This species has also been hit by the same chestnut blight, but in many areas it survives by resprouting from the roots whenever the trunk dies back. That resilience is what makes it special, a kind of stubborn refusal to disappear even under intense disease pressure. For restoration ecologists and chestnut fans, chinkapins are a reminder that the chestnut clan isn’t completely gone in American forests. They’re the tough younger sibling still standing in the understory, waiting for their moment in the sun.

6. Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) – A “Fossil” That Came Back

The dawn redwood has one of the most dramatic comeback stories in botany. For a long time, scientists only knew it from fossils and believed it had been extinct for millions of years. Then, in the nineteen forties, living trees were discovered in remote valleys in China, turning what was thought to be a fossil into a very real, very alive species.

Seeds were brought to the United States soon after, and now you can find dawn redwoods in parks, arboretums, and yards across the country. It’s a deciduous conifer, meaning it looks like an evergreen relative of redwoods and bald cypress but drops its soft, feathery needles in the fall. The tree grows quickly and can reach impressive heights, creating a strong vertical presence wherever it’s planted. Even though it’s not native to America, its story is deeply woven into American conservation and horticulture, and standing under one feels a bit like stepping into prehistory.

7. Pondcypress (Taxodium ascendens) – The Subtle Swamp Specialist

Most people have heard of bald cypress, the iconic tree with knobby knees rising from bayous and southern swamps. The pondcypress is its quieter cousin, native to the southeastern United States, and often overlooked even by locals. It tends to grow in still, acidic waters like ponds and shallow depressions, with more slender, upward-pointing leaves that give it a delicate, feathered look.

The wood, like other cypresses, is naturally resistant to rot, and the tree can shrug off flooding and poor soils that would kill most species. Its knees are usually smaller or less pronounced than those of the bald cypress, which has made some people question exactly how and why they form. As climate change brings more intense storms and shifting water patterns, pondcypress stands may become increasingly important for stabilizing wetlands and providing habitat. It’s special because it thrives in the kinds of soggy, overlooked places that quietly protect downstream communities from floods.

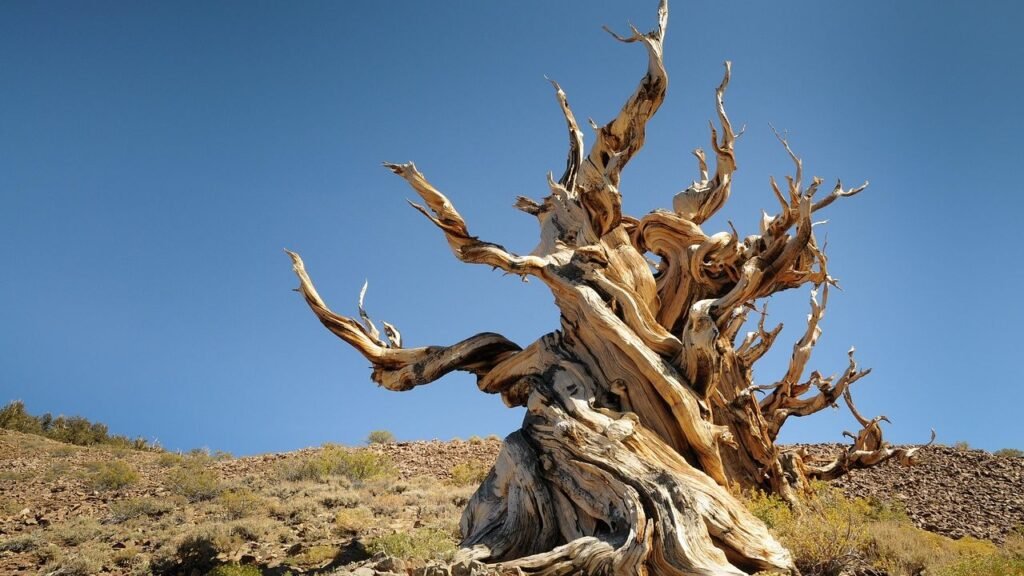

8. Bristlecone Pine (Pinus longaeva) – The Ancient Survivors of the West

High in the White Mountains of California and scattered across other harsh western slopes, the Great Basin bristlecone pine lives a life that hardly seems possible. Some individuals have been dated to nearly five thousand years old, making them among the oldest known non-clonal trees on Earth. Their twisted, weather-beaten trunks look like sculpture, with dead wood and living tissue wrapped together in patterns shaped by centuries of wind, ice, and drought.

What makes them special isn’t just their age, but their strategy. They grow painfully slowly, often in rocky soils where almost nothing else can survive, trading speed for longevity. Their wood is so dense and resin-rich that even dead trees can stand for thousands of years without rotting away. Scientists use bristlecone growth rings to reconstruct past climates, turning these trees into natural timekeepers that carry a record of droughts, storms, and temperature shifts across millennia.

9. Pacific Madrone (Arbutus menziesii) – The Peeling Beauty of the West Coast

Along the Pacific coast from California up into British Columbia, the Pacific madrone stands out like it’s perpetually sunburned. Its bark peels away in paper-thin curls, revealing smooth new bark underneath that can glow in shades of orange, red, and even pale green. The contrast of that vivid trunk with its glossy dark leaves makes it one of the most striking native trees of the American West.

In spring, clusters of small white flowers attract pollinators, followed by bright red or orange berries that feed birds and other wildlife. The wood is dense and beautiful, but the tree can be tricky to transplant or cultivate, which has kept it from becoming a mainstream landscaping choice. In many places, madrone struggles with fungal diseases and development pressure, especially as coastal climates shift. It’s special because it feels both wild and delicate, a tree that absolutely belongs on rocky coastal slopes and refuses to fully adapt to human neatness.

10. Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum) – The Moss-Covered Giant of the Northwest

In the Pacific Northwest, the bigleaf maple quietly owns the understory in many moist forests. As its name suggests, its leaves are massive, sometimes as big as a dinner plate, creating broad, shady canopies. The branches often turn into miniature hanging gardens, draped with mosses, lichens, and ferns that soak up the region’s frequent rains.

Unlike its more famous sugar maple cousin in the East, bigleaf maple has only fairly recently gained attention for syrup production, and small producers have started tapping it for a distinctly rich, caramel-like syrup. The wood has beautiful figure and is prized for musical instruments and fine woodworking. In a forest full of conifers, bigleaf maple adds a splash of deciduous drama, with golden fall color and sprawling limbs that seem to hold entire ecosystems on their backs. It’s special because it shows how one tree can be both a structural giant and a living apartment complex for countless other species.

Seeing the Forest for the Hidden Trees

The United States is full of trees that rarely show up in field guides on coffee tables, yet each one carries a powerful story about survival, loss, adaptation, and deep time. From the ghostly Franklin tree and embattled Florida torreya to the ancient bristlecones and peeling madrones, these species remind us that forests aren’t just backdrops, they’re living archives. Many of these trees are clinging to existence in shrinking habitats or changing climates, while others are slowly being rediscovered and appreciated in new ways.

Once you start noticing them, it’s hard to go back to thinking of “trees” as a generic green blur. You see the odd fruits, the peeling bark, the swamp roots, the fossil history written in living wood, and you realize how much of the natural world you’ve been walking past without really meeting. Maybe the next time you’re on a hike, in a park, or even just driving down a back road, you’ll wonder what rare or overlooked species might be standing just out of sight. Which of these quiet, unusual trees do you hope to meet in person one day?