Have you ever wondered how a single bone fragment could spark decades of scientific debate, or how entire careers were built on fossils that turned out to be complete fabrications? The world of paleontology is filled with breathtaking discoveries that rewrite our understanding of ancient life, but it’s also littered with spectacular mistakes that remind us just how fallible human interpretation can be. From hoaxes that fooled entire scientific communities to genuine fossils that were so bizarre they were dismissed as fakes, the history of fossil hunting is as much about getting things wrong as it is about getting them right.

The Piltdown Man: Science’s Greatest Embarrassment

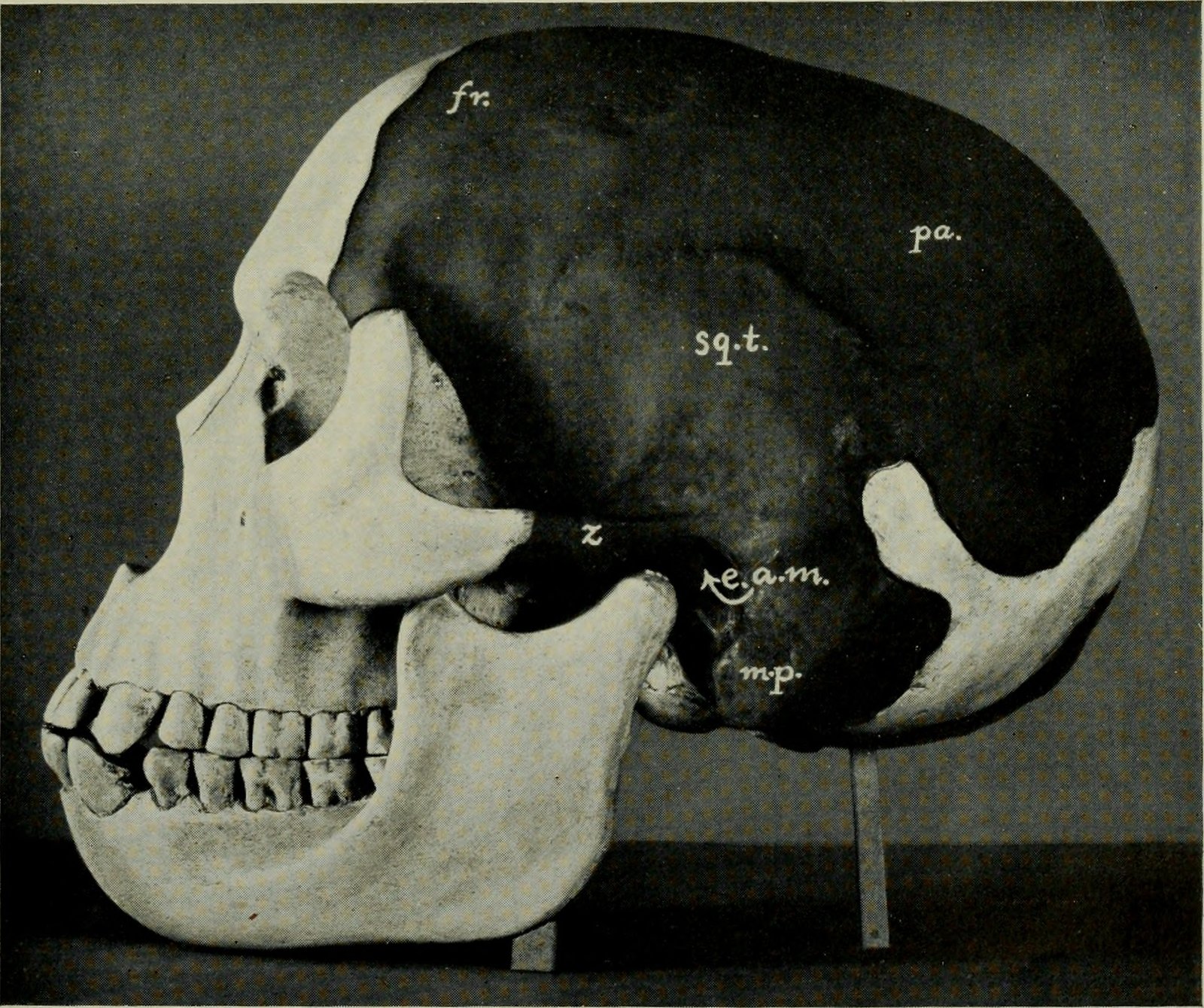

In 1912, amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson claimed to have discovered the “missing link” between apes and humans in a gravel pit near Piltdown, England. The skull fragments appeared to show a creature with a human-like cranium but an ape-like jaw, perfectly fitting the evolutionary expectations of the time. For over 40 years, Piltdown Man was hailed as one of the most important discoveries in human evolution, featured in textbooks and museums worldwide.

The truth was far more embarrassing. In 1953, advanced dating techniques revealed that the skull was actually a medieval human cranium paired with the jaw of a modern orangutan, artificially aged with chemicals and filed to appear ancient. The hoax had fooled some of the world’s leading scientists for decades, highlighting how preconceived notions about evolution could blind researchers to obvious inconsistencies.

Archaeoraptor: The Feathered Fake That Shocked National Geographic

When National Geographic announced the discovery of Archaeoraptor liaoningensis in 1999, it seemed like the perfect transitional fossil between dinosaurs and birds. The specimen appeared to have the body of a small dinosaur with clear feather impressions, seemingly providing the missing link that would prove birds evolved from dinosaurs. The magazine featured it prominently, calling it one of the most important discoveries of the century.

Unfortunately, Archaeoraptor was too good to be true. Chinese fossil dealers had cleverly glued together parts from different fossils – the tail of a small dinosaur, the body of a primitive bird, and other fragments – to create a more valuable specimen. The hoax was eventually exposed when scientists noticed that the tail didn’t quite match the body, but not before it had caused significant embarrassment to the scientific community and raised questions about the fossil trade.

Brontosaurus: The Dinosaur That Never Existed

For over a century, Brontosaurus was one of the most beloved dinosaurs in popular culture, appearing in countless movies, books, and museum displays. The massive, long-necked creature captured imaginations and became synonymous with the age of dinosaurs. Children grew up learning about this gentle giant that supposedly roamed North America millions of years ago.

The problem was that Brontosaurus never actually existed as a distinct species. In 1877, paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh discovered a nearly complete skeleton and named it Brontosaurus excelsus, meaning “thunder lizard.” However, it was later determined that this skeleton was actually just a larger, more complete specimen of Apatosaurus, which had been named earlier. The scientific community officially retired the name Brontosaurus in 1903, though it took decades for museums and popular culture to catch up.

The Cardiff Giant: America’s Greatest Archaeological Hoax

In 1869, workers digging a well on a farm in Cardiff, New York, made what seemed like an incredible discovery – a 10-foot-tall petrified man buried in the ground. News of the “Cardiff Giant” spread like wildfire, with thousands of people paying to see what many believed was proof of the biblical giants mentioned in Genesis. Scientists and religious leaders debated whether this was a fossilized human or an ancient statue.

The truth was much more mundane and devious. The Cardiff Giant was actually a elaborate hoax created by George Hull, a tobacconist who had gotten into an argument about biblical literalism. Hull had commissioned a block of gypsum to be carved into the shape of a giant man, then buried it on his cousin’s farm to be “discovered” later. The hoax made Hull wealthy but also demonstrated how easily people could be fooled when discoveries seemed to confirm their existing beliefs.

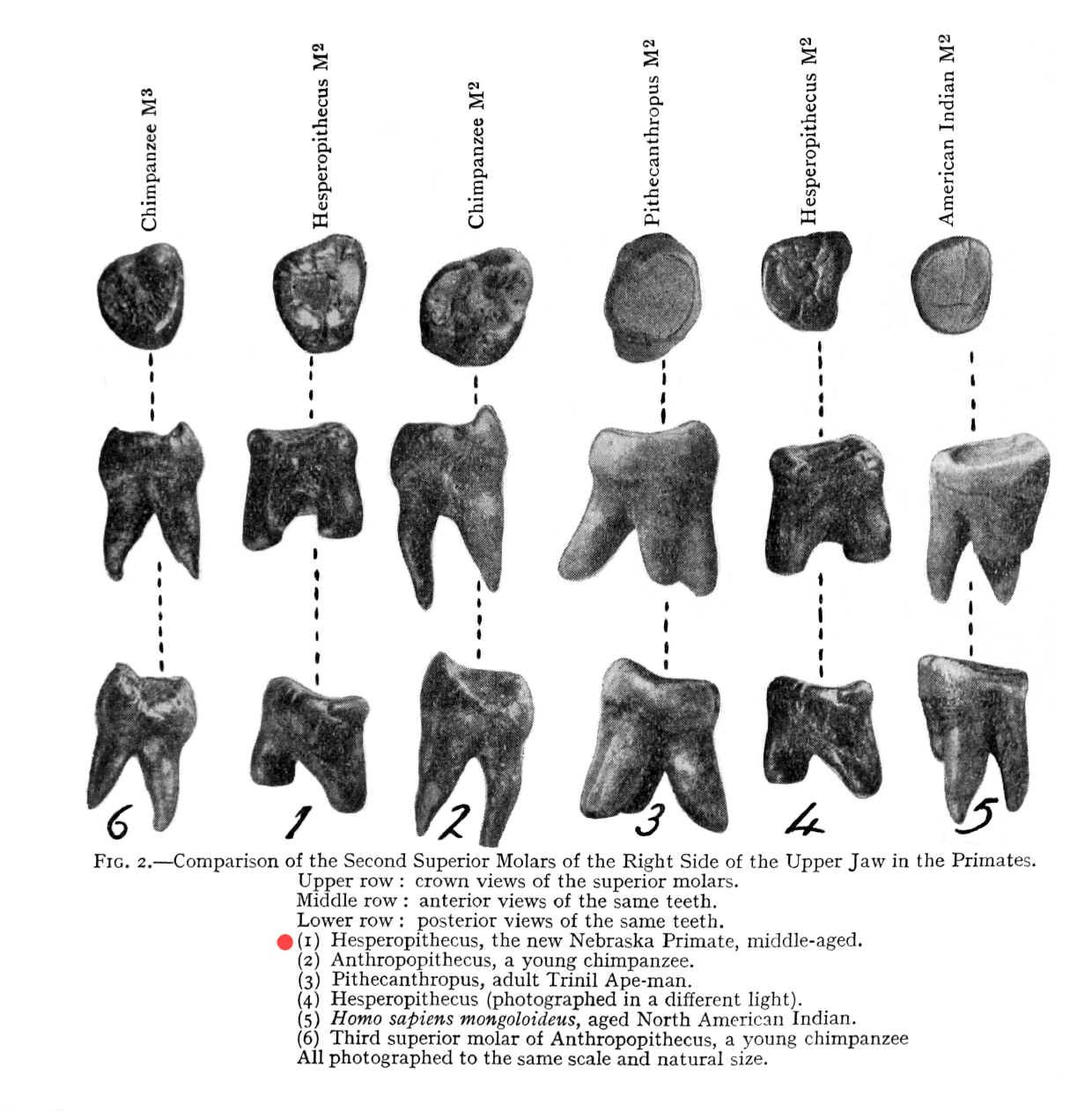

Nebraska Man: Building an Entire Species from One Tooth

In 1922, geologist Harold Cook discovered a single tooth in Nebraska that would spark one of paleontology’s most embarrassing episodes. The tooth was examined by prominent paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, who declared it belonged to an early human ancestor and named it Hesperopithecus haroldcookii, or “Nebraska Man.” The discovery was hailed as evidence that human evolution had occurred in North America, not just Africa and Asia.

Artists even created detailed reconstructions of what Nebraska Man and his family might have looked like, complete with primitive tools and cave dwellings. The scientific community was divided, with some embracing the discovery while others remained skeptical. In 1927, more complete fossil remains were found at the same site, revealing the embarrassing truth – the tooth belonged to an extinct species of pig, not a human ancestor at all.

The Lying Stones of Würzburg: When Professors Played Pranks

In the early 18th century, Johann Bartholomew Adam Beringer, a respected professor at the University of Würzburg, began discovering remarkable fossils on a local hillside. These weren’t ordinary fossils – they included perfectly preserved spiders caught in their webs, birds in flight, and even Hebrew letters spelling out the name of God. Beringer was convinced he had discovered proof of divine creation and began writing a book about his findings.

The truth was far more humiliating. Beringer’s own colleagues had been secretly planting carved limestone “fossils” for him to find, intending it as a harmless prank to mock his gullibility. When Beringer published his book about the “Lying Stones,” his colleagues finally revealed the hoax. The incident became a cautionary tale about the importance of peer review and skeptical thinking in scientific research.

Orce Man: The Skull That Wasn’t Human

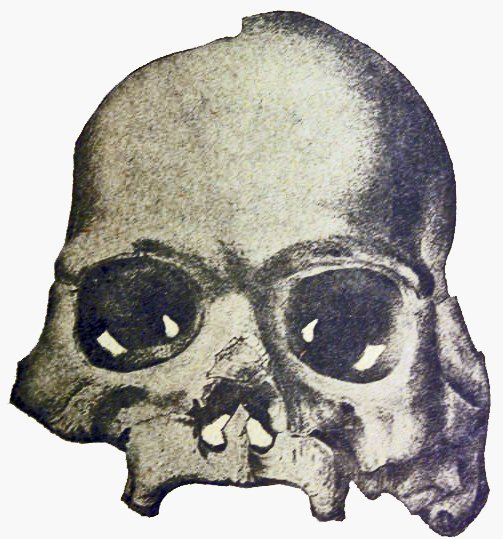

In 1982, Spanish archaeologists announced the discovery of what they claimed was the oldest human fossil ever found in Europe. The skull fragment, found in Orce, Spain, was dated to 1.8 million years old and seemed to represent an early human ancestor that had migrated from Africa. The discovery made international headlines and was celebrated as a major breakthrough in understanding human evolution.

However, other scientists were skeptical from the beginning. The skull fragment was very small and showed characteristics that didn’t quite fit with known human fossils. After years of debate and additional analysis, most experts now believe the Orce skull actually belonged to a young donkey or horse, not a human ancestor. The controversy highlighted how difficult it can be to identify fragmentary fossils and how scientific consensus can take years to develop.

The Solenhofen Archaeopteryx Forgery Accusations

When the first Archaeopteryx fossil was discovered in 1861 in Germany’s Solnhofen limestone quarries, it seemed almost too perfect to be real. The specimen showed clear feather impressions around what was obviously a reptilian skeleton, providing stunning evidence for the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds. However, the timing was suspicious – the fossil was found just two years after Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” and some critics accused museum officials of creating a fake to support evolutionary theory.

The accusations persisted for decades, with some scientists claiming the feathers had been artificially added to a dinosaur fossil using cement and carved limestone. In the 1980s, advanced imaging techniques finally proved that the feathers were genuine and had been preserved naturally. The Archaeopteryx controversy showed how scientific discoveries that challenge existing beliefs often face intense scrutiny, even when the evidence is overwhelming.

The Bone Wars: When Competition Led to Sloppy Science

During the late 19th century, two prominent paleontologists, Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, engaged in a bitter rivalry known as the “Bone Wars.” Their competition to discover new dinosaur species led to increasingly rushed and sloppy work, with both men making numerous errors in their haste to publish first. Cope alone published over 1,400 scientific papers, many containing mistakes that took decades to correct.

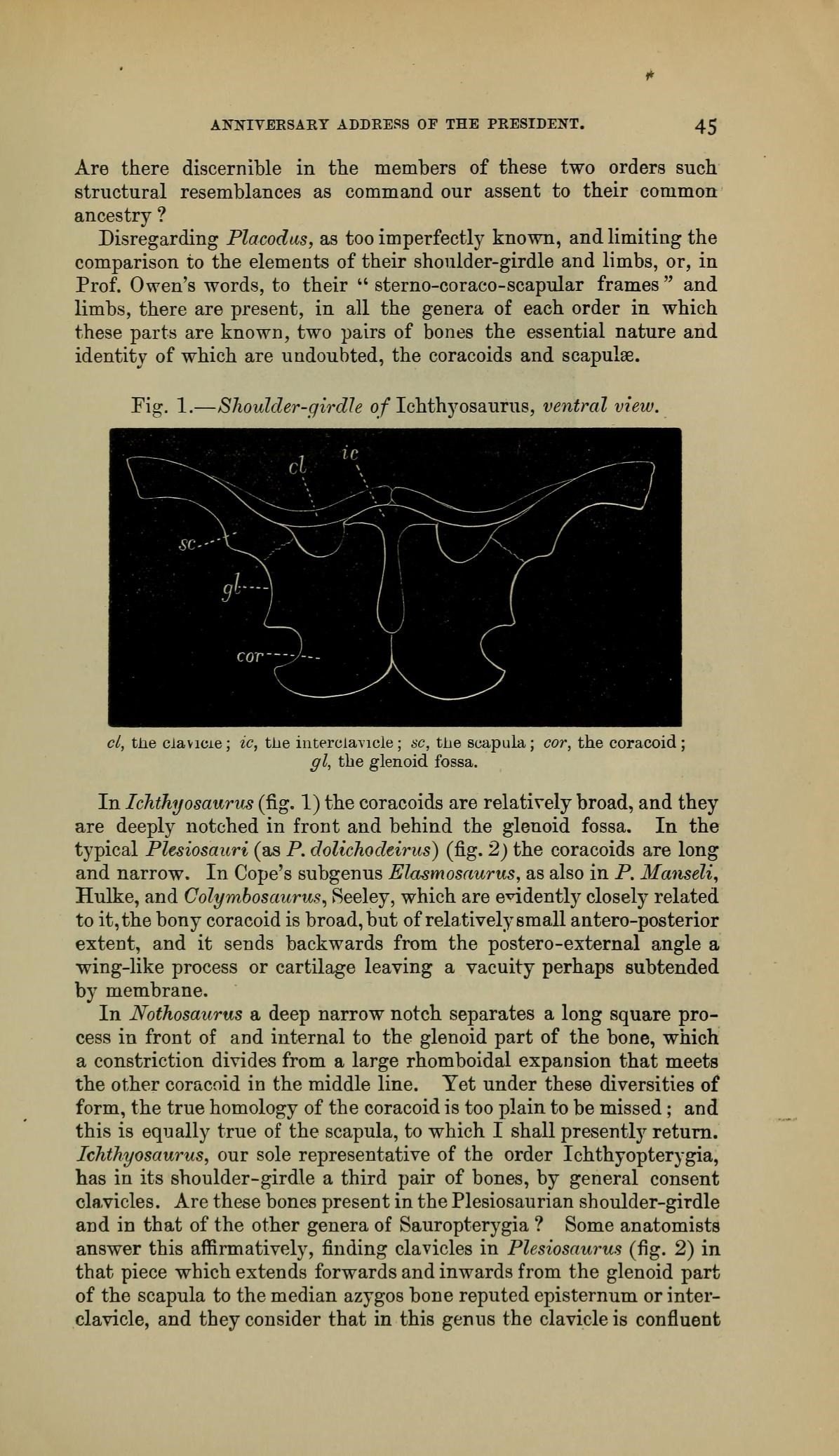

One of the most famous errors occurred when Cope reconstructed the marine reptile Elasmosaurus with its head on the wrong end of its body. When Marsh pointed out the mistake, Cope was so embarrassed that he tried to buy back all copies of his publication. The Bone Wars demonstrated how personal rivalries and the pressure to publish quickly could compromise scientific accuracy and peer review.

Dickinsonia: The Fossil That Confused Scientists for Decades

For over 70 years, one of the most abundant fossils from the Ediacaran period remained a complete mystery. Dickinsonia appeared as oval-shaped impressions with ribbed patterns, but scientists couldn’t agree on what kind of organism it represented. Some thought it was a primitive jellyfish, others suggested it was a type of worm, and still others believed it might be a fungus or even a bacterial mat.

The confusion stemmed from the fact that Dickinsonia lived 558 million years ago, before the development of shells, bones, or other hard parts that typically preserve well as fossils. In 2018, Russian scientists finally solved the mystery by analyzing cholesterol molecules preserved in the fossil – proving that Dickinsonia was actually one of the earliest known animals. The discovery showed how chemical analysis could unlock secrets that traditional paleontology couldn’t reveal.

The Calaveras Skull: A Mining Town’s Practical Joke

In 1866, miners in Calaveras County, California, reportedly discovered a human skull buried deep underground in gold-bearing gravels that were millions of years old. The skull seemed to prove that humans had lived in North America far earlier than anyone had imagined, potentially rewriting the entire history of human migration. The discovery was championed by state geologist Josiah Whitney, who used it as evidence for his theories about early human presence in the Americas.

Unfortunately, the Calaveras Skull was almost certainly a prank played by bored miners on gullible scientists. The skull showed clear signs of being from a recent Native American burial, and several miners later admitted to planting it as a joke. The incident became a cautionary tale about the importance of proper archaeological context and the dangers of accepting extraordinary claims without extraordinary evidence.

Megalosaurus: The First Dinosaur That Wasn’t What It Seemed

When Megalosaurus became the first dinosaur to be scientifically named in 1824, Victorian scientists had no idea what they were dealing with. Based on incomplete fossil remains, they reconstructed it as a massive, four-legged lizard-like creature that crawled on its belly like a crocodile. Museums displayed models showing Megalosaurus as a sluggish, dragon-like beast that barely lifted its body off the ground.

This interpretation persisted for decades until more complete fossils revealed the truth – Megalosaurus was actually a bipedal predator that walked upright on its hind legs, more like a giant bird than a lizard. The mistake wasn’t anyone’s fault; early paleontologists were working with limited fossil evidence and no modern understanding of dinosaur biology. The Megalosaurus mix-up showed how scientific knowledge evolves as new evidence becomes available.

The Paluxy River Tracks: When Dinosaurs Walked with Humans

In the 1930s, amateur fossil hunters began reporting human footprints alongside dinosaur tracks in the limestone beds of the Paluxy River in Texas. The discovery seemed to provide evidence that humans and dinosaurs had coexisted, directly contradicting the scientific understanding of Earth’s history. Young-earth creationists embraced the Paluxy tracks as proof that evolution was wrong and that the Earth was only thousands of years old.

Careful scientific analysis later revealed that the “human” footprints were actually made by dinosaurs walking on their metatarsals (the middle part of their feet), creating elongated impressions that superficially resembled human tracks. Some tracks had also been carved or enhanced by local residents hoping to attract tourists. The Paluxy River controversy highlighted how preconceived beliefs could lead people to see patterns that weren’t really there.

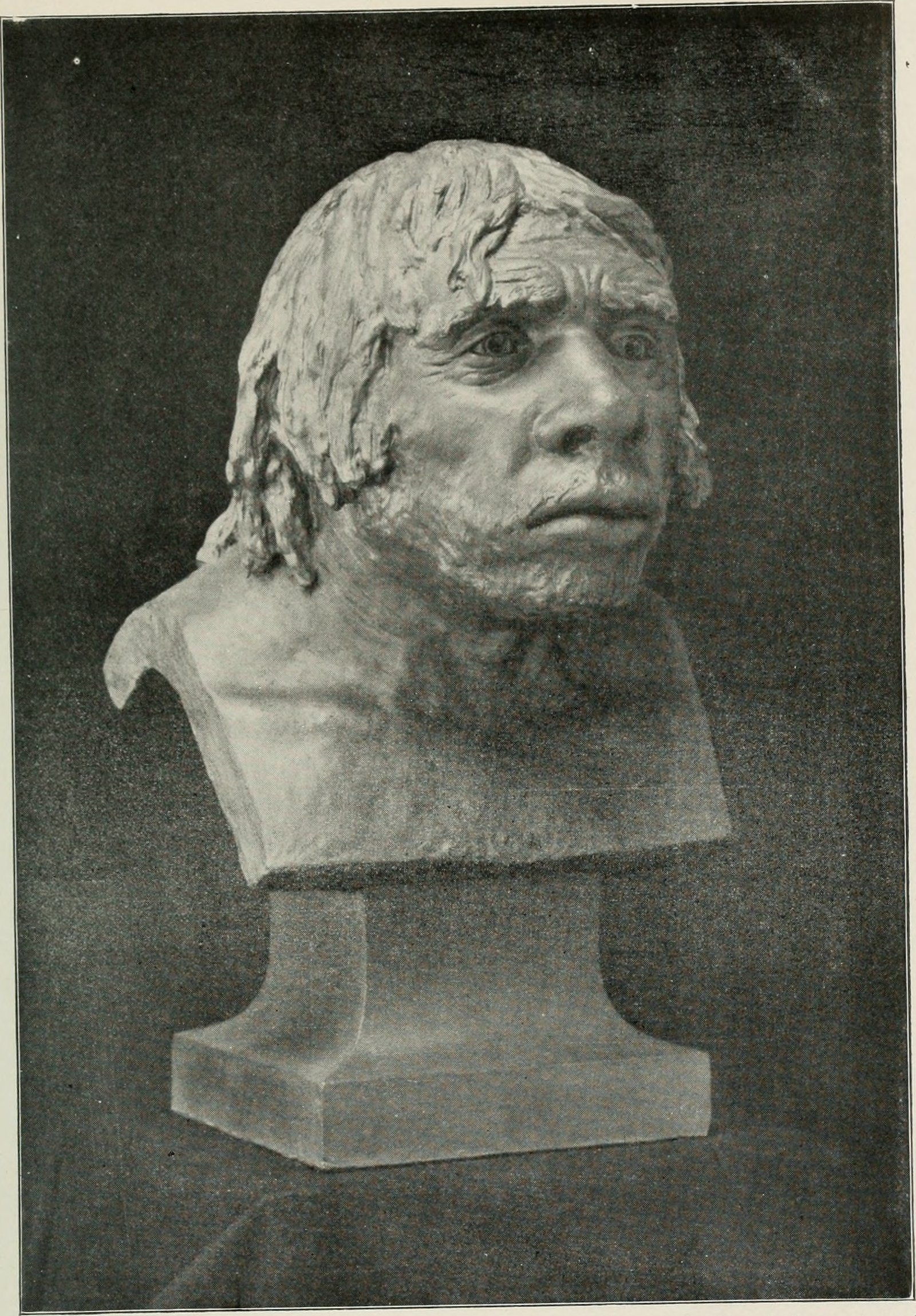

Boule’s Neanderthal: The Ape-Man Who Wasn’t

When French paleontologist Marcellin Boule reconstructed the first relatively complete Neanderthal skeleton in 1911, he depicted our ancient cousins as brutish, ape-like creatures who walked with a stooped posture and couldn’t fully straighten their legs. This reconstruction shaped public perception of Neanderthals for decades, portraying them as primitive “cavemen” who represented a failed branch of human evolution.

Boule’s reconstruction was fundamentally flawed. The skeleton he studied belonged to an elderly individual who suffered from severe arthritis and other age-related conditions that affected his posture. Modern analysis has shown that healthy Neanderthals walked upright and had brain sizes similar to or even larger than modern humans. The mistake demonstrated how individual specimens could provide misleading information about entire species, especially when researchers brought their own biases to the interpretation.

The Plumed Serpent That Never Flew

When paleontologists first discovered Quetzalcoatlus in the 1970s, they identified it as the largest flying animal that ever lived, with a wingspan of up to 40 feet. The massive pterosaur was named after the Aztec feathered serpent god and was thought to soar over Late Cretaceous landscapes like a prehistoric airplane. Museum displays showed Quetzalcoatlus gliding effortlessly through ancient skies, and it became an icon of prehistoric flight.

Recent biomechanical studies have suggested that Quetzalcoatlus might have been too heavy to fly effectively, if at all. Some researchers now believe it was primarily a ground-dwelling predator that used its massive size and long neck to hunt small dinosaurs and other prey. The debate over Quetzalcoatlus flight capabilities continues, but the initial assumptions about its lifestyle have been seriously challenged by new evidence and computer modeling.

When Mistakes Become Stepping Stones

The history of paleontology is filled with spectacular mistakes, hoaxes, and misinterpretations that might seem embarrassing in hindsight. Yet these errors have played a crucial role in advancing our understanding of ancient life by forcing scientists to develop better methods, ask harder questions, and remain skeptical of extraordinary claims. Each mistake has contributed to more rigorous standards of evidence and peer review that make modern paleontology more reliable than ever before.

From the Piltdown Man hoax to the Brontosaurus naming controversy, these paleontological blunders remind us that science is a human endeavor, subject to the same biases, hopes, and mistakes that affect all human activities. The key difference is that science has built-in mechanisms for self-correction that eventually expose errors and lead to better understanding. What seems like a devastating mistake today might be tomorrow’s breakthrough insight.

The next time you visit a natural history museum or read about a new fossil discovery, remember that our current understanding of ancient life is built on a foundation of countless corrections, revisions, and hard-won insights. The fossils that seemed obvious to one generation of scientists often turn out to be completely different creatures than anyone imagined. What fossil mystery do you think we’re still getting completely wrong today?