Across the United States, some waterfalls are so high they seem to fall straight out of the sky, yet many people could not name a single one beyond the famous postcard icons. Beneath the mist and roar lies a quieter story: shifting rock layers, shrinking glaciers, and changing snowfall patterns that are already reshaping the country’s tallest cascades. Scientists are now measuring drops to the meter, revising old claims, and even debating which waterfalls count at all when climate change turns once-thundering falls into seasonal trickles. At the same time, hikers continue to line up for selfies at overlooks, often unaware that these dramatic landscapes are living laboratories for geology, hydrology, and ecology. This is the strange tension at the heart of America’s tallest waterfalls: they are both bucket-list destinations and delicate scientific instruments etched into stone.

The Hidden Giants: Waterfalls Taller Than Most Skyscrapers

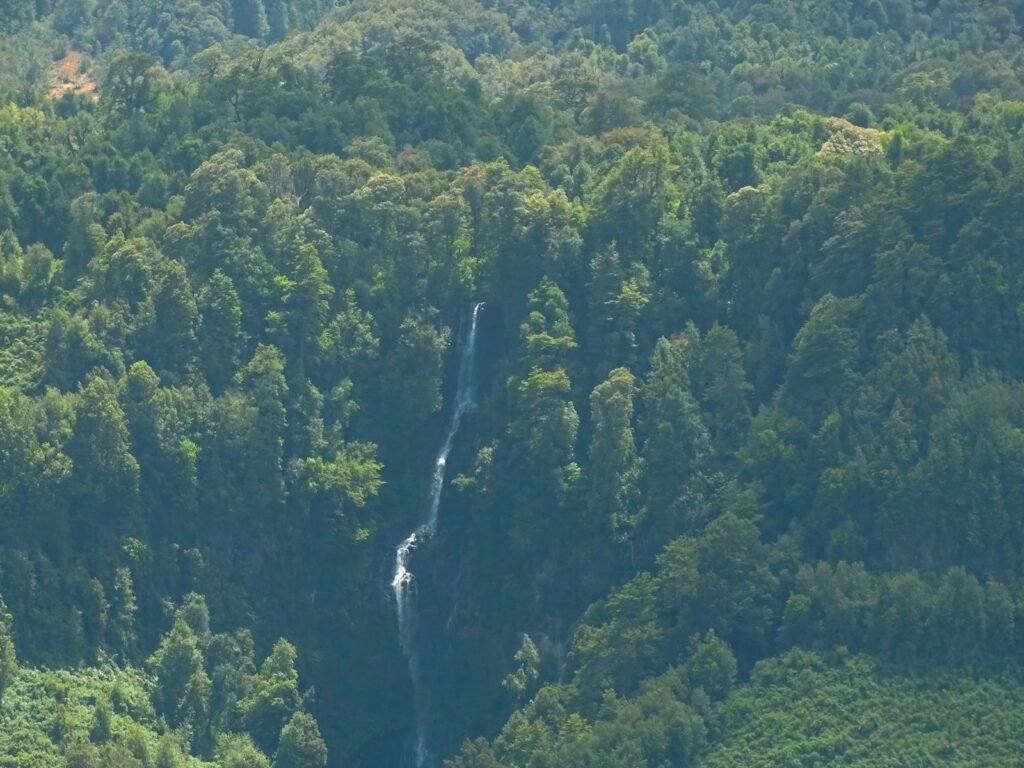

Ask someone to name a tall waterfall in the United States, and you’ll likely hear “Yosemite” before anything else, but the full list of the country’s tallest falls is far more surprising and scattered than most people realize. Beyond the famous names are remote giants like Olo’upena and Pu’uka’oku Falls on Molokaʻi in Hawaii, which plunge down nearly sheer sea cliffs and are so isolated that most people only ever see them from the air. These coastal waterfalls form where relentless ocean erosion carves into volcanic rock, leaving towering pali (cliffs) that capture rainfall and funnel it in silver threads straight to the Pacific. In the Pacific Northwest, Stratosphere-level drops such as Colonial Creek Falls in Washington plunge down deeply carved glacial valleys, formed where ice once bulldozed its way through the North Cascades. The result is a kind of vertical geography that only really makes sense when you imagine the continent as a giant, slowly melting sculpture.

Even within iconic parks, the true giants can feel strangely invisible. In Yosemite National Park, Yosemite Falls commands the crowds, yet neighboring Ribbon Fall, a seasonal cascade that drops along the western wall of Yosemite Valley, rivals much of the world for single-drop height when it is in full flow. Vapors from these towering falls can create localized microclimates, slightly cooling and moistening the air just enough to favor mosses, ferns, and cliff-dwelling plants that would struggle only a few meters away. Standing at an overlook, you are not just watching water drop; you are watching gravity reshape the air, rock, and life along a vertical corridor. It is this collision of scale and subtlety that makes the ten tallest waterfalls in the United States feel far larger than any top-ten list can capture.

From Volcanic Cliffs to Glacial Valleys: How These Falls Were Born

The tallest waterfalls in the country are not accidents of scenery; they are the visible scars of very different geologic stories. Along the wind-battered cliffs of Molokaʻi, Hawaiian waterfalls like Olo’upena and Pu’uka’oku fall down enormous sea cliffs created when parts of ancient shield volcanoes collapsed and slid toward the ocean. Over millions of years, waves attacked the exposed rock, cutting it steeper and steeper until the mountainsides became near-vertical walls, perfect launch pads for narrow, lofty waterfalls. In stark contrast, the enormous drops in places like Yosemite or the North Cascades in Washington were carved by glaciers that once filled entire valleys with ice as thick as city skyscrapers. As the glaciers retreated, they left behind hanging valleys – side valleys perched high above the main canyon – that now spill their streams abruptly into empty space.

Hydrologists and geomorphologists love these places because they stitch together multiple chapters of Earth history in a single view. The rock layers reveal changes in volcanic activity, sediment deposits, and faulting, while the shape of the canyon tells the story of where ice ground the hardest and where meltwater later tore through. At the lip of a big drop, you can often see a literal line in the stone – one type of rock over another – that controls exactly where the water breaks over. Over time, the plunge pools at the base act like natural jackhammers, slowly carving backward into the cliff and gradually shifting the waterfall upstream. Taken over tens of thousands of years, these ten giants are not fixed landmarks at all; they are slowly walking backwards into the mountains that created them.

Measuring the Drop: The Tallest Contenders, Ranked

Ranking the tallest waterfalls in the United States sounds simple until you realize no one fully agrees on what should count as a “waterfall.” Many of the country’s highest drops, such as Colonial Creek Falls and Johannesburg Falls in Washington, are made up of multiple cascades and horsetails, broken up by sloping rock and ledges that only carry water part of the year. When surveyors and researchers set out to measure these falls, they now use high-resolution laser mapping, drone-based photography, and GPS to track the full vertical distance from the highest spill to the lowest recognizable plunge. These more precise methods have bumped some rivals up the list and pushed others down, revealing that older guidebook numbers were often generous guesses rounded to the nearest dramatic figure. In practical terms, the difference between a fall that drops roughly about two thousand six hundred feet and one that drops slightly less does not change your sense of awe, but it matters to scientists trying to standardize Earth’s extremes.

Despite the nuance, a handful of names consistently appear at the top. Among the most widely cited are Olo’upena Falls and Pu’uka’oku Falls on Molokaʻi, Colonial Creek Falls and Johannesburg Falls in Washington’s North Cascades, and Yosemite Falls and Ribbon Fall in California’s Sierra Nevada. Several of these exceed the height of many urban skyscrapers by a comfortable margin, with some total drops stretching well over half a mile. What complicates the rankings further is seasonality: some of the tallest candidates are ephemeral, running strongly only during snowmelt or after heavy rain, while others are spring-fed and far more consistent through the year. This has led some researchers to sort waterfalls not into a single top ten, but into overlapping categories such as tallest perennial falls, tallest seasonal falls, and tallest single-drop cascades. It is a reminder that nature rarely cares about our leaderboards.

The Science in the Spray: Microclimates, Mist, and Life on the Edge

Step close to any major waterfall and you can feel the physics on your skin: a cool blast of air, tiny droplets of mist, a low roar that seems to vibrate in your chest. That sensation is more than drama; it is a small example of how falling water transfers energy to the surrounding environment. As water accelerates under gravity, it breaks apart when it slams into rocks and plunge pools, throwing up clouds of spray that can cool the air and slightly raise local humidity. Over time, this constant misting can carve out specialized microhabitats, home to mosses, liverworts, ferns, and moisture-loving insects that thrive only within the narrow zone of spray. In some tall, shaded canyons, roughly about one third of the plant species clustered near the falls may differ from those just a short hike away on drier slopes.

Researchers working in waterfall gorges also pay close attention to how these microclimates buffer organisms against broader climate shifts. Cooler, wetter pockets near the base of large falls may act as refuges for amphibians and invertebrates during heat waves, much like air-conditioned alcoves in a stone cathedral. Birds exploit the rising columns of mist and moving air for foraging and nesting, while certain bats use the complex echoes of falling water to navigate and hunt. Even the rock faces themselves support fragile communities of lichen and algae that scrub tiny amounts of carbon and pollutants from the air and water. When you stand under one of the tallest waterfalls in the United States, you are not just looking at a dramatic backdrop; you are standing in the middle of a compact, high-energy ecosystem powered by gravity and turbulence.

Why It Matters: Waterfalls as Climate Barometers and Cultural Anchors

It is tempting to treat tall waterfalls as static icons – a kind of natural architecture that will always be there – but scientists are already using them as sensitive gauges of climate and hydrologic change. The flow of a high waterfall depends on a delicate balance of snowpack, rainfall, and groundwater recharge in its upstream basin, and that balance is shifting. In parts of the West, warming temperatures are driving snow to melt earlier in the year, which can leave once-roaring summer waterfalls running much lower or even dry by mid-season. Over the last few decades, observational records at popular parks have shown noticeable shifts in peak flow timing and the duration of strong waterfall seasons, a change that both visitors and researchers are starting to track more closely. The tallest falls amplify these seasonal signals, making them especially useful as natural barometers of changing water cycles.

Beyond the science, these waterfalls hold deep cultural weight. For Indigenous communities across Hawaii, California, and the Pacific Northwest, particular falls and cliff faces are embedded in stories that tie people to place and water to ancestry. Modern tourism has layered on new meanings, turning some of the tallest falls into economic engines that help sustain surrounding communities, guide services, and conservation efforts. At the same time, heavy visitation brings real pressure: trampled vegetation along viewpoints, erosion on steep trails, and safety risks as more people try to push past barriers for a better angle. Thinking about the ten tallest waterfalls in the United States as both climate indicators and cultural landmarks forces a harder question: how do we protect something that is at once fragile, sacred, profitable, and in motion?

Global Context: How America’s Tallest Compare to the World’s Great Cascades

When you zoom out to the global scale, the tallest waterfalls in the United States sit in a competitive but not dominant league. Iconic giants like Angel Falls in Venezuela or Tugela Falls in South Africa still surpass most American contenders in overall height, dropping through tropical clouds or plunging down ancient escarpments that dwarf even the steepest U.S. canyons. Yet the American list stands out for its diversity: volcanic sea cliffs in Hawaii, glaciated granitic walls in California, and rugged alpine cirques in Washington all host candidates for the top-ten roster. Each of these settings tells a different climate story, from trade-wind-fed rainfall on island slopes to snowmelt-driven torrents in continental mountain ranges. In that sense, the United States offers a kind of living catalog of how different Earth systems can all arrive at the same spectacle of a long, uninterrupted fall.

Scientists studying waterfalls increasingly share methods and data across continents, comparing everything from erosion rates to spray-zone biodiversity. High-resolution mapping techniques developed for remote South American cascades are being repurposed to refine measurements of U.S. falls, while field studies of mist-adapted plants in Europe help frame questions about similar species along American cliffs. There is also a shared concern that many of the world’s tallest waterfalls are at risk from the same pressures: warming temperatures, altered river flows due to dams and diversions, and surging visitor numbers chasing social-media-famous views. Looking at the U.S. giants alongside their global peers drives home an uncomfortable truth. These are not permanent monuments; they are dynamic features on a planet in flux, and their fate is tightly bound to choices being made far downstream and far away.

The Future Landscape: How Climate, Technology, and Tourism May Reshape the Top Ten

Projecting the future of the tallest U.S. waterfalls is a bit like forecasting the fate of mountain glaciers: we know the general direction, but the local details will make all the difference. In high western ranges, rising temperatures are expected to reduce snowpack and accelerate melt, likely shortening the season of peak flow for many tall, snow-fed falls. That could push some famously photogenic cascades toward increasingly brief, intense bursts of power rather than steady, long-running displays. On volcanic islands like Molokaʻi, shifts in rainfall patterns and storm intensity may alter how often the towering cliffside falls run at full strength, changing what visitors see from tour boats and aircraft. At the same time, rockfalls and landslides – already a natural part of steep terrain – may become more frequent in freeze–thaw-prone zones, subtly re-sculpting the exact lip and drop of some cascades.

Technology will almost certainly change how we monitor and experience these giants. Remote sensors, satellite imagery, and repeat drone surveys are already being used to track waterfall flow and cliff stability with far greater precision than past field expeditions could manage. In the next decade or two, we may see real-time waterfall dashboards in major parks, showing live flow rates and spray-zone conditions, much like river gauges and wildfire maps today. Virtual and augmented reality tools could allow people to explore precarious cliffside angles or off-limits aerial views without physically crowding fragile ledges. Yet these tools come with dilemmas: if every waterfall can be experienced safely from a couch, does that lessen the political will to protect the real, messy, dangerous landscapes that create them? The answer will help decide which falls remain wild and which become ever more curated experiences at the edge of a cliff.

How to Engage: Visiting, Protecting, and Paying Attention

For most of us, the first connection to these towering waterfalls is simple awe: the first time you round a bend in a trail and see a thin white ribbon dropping down a dark cliff for what feels like forever. That feeling is a powerful entry point into deeper engagement, but it comes with responsibility. When planning visits to any of the tallest waterfalls in the United States – whether in Hawaii, Washington, or California – it helps to think like both a guest and a guardian. Staying on marked trails, respecting closures, and giving wildlife and cliff edges a wide berth are small actions that collectively reduce damage in places that are already naturally unstable. Supporting local Indigenous-led tours or community groups, where they exist, adds another layer of respect to what can otherwise become a purely recreational encounter.

There are also quieter ways to engage from home. Paying attention to seasonal flow updates from parks, following scientific field projects that focus on waterfall ecosystems, or even supporting organizations that work on watershed conservation all feed back into the long-term health of these vertical landscapes. Simple choices – like reducing water waste, backing policies that protect headwaters, or learning the names and histories of the falls you see in photographs – help tie personal decisions to distant cliffs. If the ten tallest waterfalls in the United States are gravity’s most dramatic signatures on the landscape, then our collective choices are the small but accumulating notes in the margins. The next time you see a picture of water vanishing into mist off a cliff, it is worth asking: what will that same view look like in fifty years, and what role did we play in the answer?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.