Have you ever stared at an image and felt your brain twist into a knot trying to make sense of what you’re seeing? Optical illusions aren’t just party tricks or internet curiosities. They’re windows into one of the most complex systems in the known universe: your brain.

When you experience an optical illusion, you’re witnessing a fascinating disconnect between what’s actually in front of you and what your brain tells you is there. Here’s the thing: your visual system isn’t designed to be a perfect camera. It’s designed to keep you alive, make quick decisions, and fill in gaps when information is missing. Sometimes, that means your brain takes shortcuts, makes assumptions, or gets completely fooled by clever patterns. Let’s dive into ten illusions that pull back the curtain on how your mind really works.

The Müller-Lyer Illusion: When Context Warps Reality

Picture two lines of exactly the same length sitting side by side. Now, add arrowheads pointing outward on one line and inward on the other. Suddenly, one line looks noticeably longer than the other, even though they’re identical. This is the Müller-Lyer illusion, and it’s been baffling people since 1889.

Your visual system learns that the “angles in” configuration corresponds to a rectilinear object, such as the convex corner of a room, which is closer, and the “angles out” configuration corresponds to an object which is far away, such as the concave corner of a room. Your brain is essentially trying to interpret a flat image as three-dimensional. It’s applying depth cues that work brilliantly in the real world but get hijacked by this simple drawing.

Interestingly, research comparing different cultures found that the mean fractional misperception varied from 1.4% to 20.3%, with European-derived samples being the three most susceptible while San foragers of the Kalahari desert were the least susceptible, and people in different cultures differ substantially on how they experience the Müller-Lyer stimuli. If you grew up surrounded by buildings, right angles, and straight corridors, your brain is more vulnerable to this trick.

The Ponzo Illusion: Depth Perception Gone Wrong

Imagine two horizontal lines, perfectly equal in length, placed between two converging lines that look like railroad tracks vanishing into the distance. In the Ponzo illusion the converging parallel lines tell the brain that the image higher in the visual field is farther away, therefore, the brain perceives the image to be larger, although the two images hitting the retina are the same size. Your brain sees those converging lines and immediately thinks “distance.” It then compensates by making the upper line appear larger.

This illusion taps into size constancy, which is your brain’s ability to perceive objects as maintaining their actual size even when they’re far away and appear smaller on your retina. Research by Segall, Campbell and Herskovits found that people from “carpentered” environments (with lots of straight lines and right angles, like cities) were more susceptible to the illusion than those from rural environments with fewer linear features, suggesting that perception is partly shaped by visual environment and experiences.

The Motion Aftereffect: When Stillness Moves

Stare at a waterfall for about a minute, then shift your gaze to the rocks beside it. You’ll see something bizarre: the stationary rocks appear to drift upward. This is the motion aftereffect, sometimes called the waterfall illusion, and it reveals how your brain processes movement.

Perception of stationary objects is coded as the balance among the baseline responses of neurons coding all possible directions of motion, and neural adaptation of neurons stimulated by downward movement reduces their baseline activity, tilting the balance in favor of upward movement. Essentially, the neurons responsible for detecting downward motion get tired from all that waterfall watching. When you look at something still, the “upward motion” neurons are suddenly more active by comparison, creating the illusion.

Things can appear to move without seeming to change in position – the water seems to be surging upwards but it does not get any closer to the top, suggesting that movement and position might be processed independently in the brain. It’s hard to believe, yet your visual system separates “where” from “how fast.”

The Checker Shadow Illusion: Brightness Deception

In this famous illusion, two squares on a checkerboard appear to be vastly different shades of gray. One looks dark, the other light. The shocking truth? They’re exactly the same color. The illusion tricks our brains into seeing them as different shades, with the square labeled “A” appearing much darker because it is surrounded by lighter squares, while the square labeled “B” appears lighter because it is surrounded by darker squares, and the illusion of a shadow also adds to this effect.

Your visual system doesn’t just measure light hitting your retina. It interprets lighting conditions, shadows, and context to figure out what color something “really” is. This usually helps you recognize a white shirt as white whether it’s in bright sunlight or dim lamplight. In this case, though, your brain’s shadow compensation goes into overdrive and gets fooled.

The Scintillating Grid Illusion: Phantom Dots

Look at a white grid on a black background with white circles at each intersection. The scintillating grid illusion causes the brain to perceive dark spots inside the white circles present at the intersection of grid lines, and these spots can flash in and out of peripheral vision so rapidly that some people might find it difficult to look at the illusion for too long; if you try to look directly at one of the perceived dark spots, then it will disappear.

This illusion exploits how your peripheral vision works differently from your central focus. Lateral inhibition, where in receptive fields of the retina receptor signals from light and dark areas compete with one another, has been used to explain why we see bands of increased brightness at the edge of a color difference. Your brain is constantly enhancing edges and contrasts to help you spot important details, and this grid pattern hijacks that process.

The Spinning Dancer: Ambiguity in Motion

You’ve probably seen this one circulating online: a silhouetted figure that appears to spin. Some people swear she’s rotating clockwise. Others insist it’s counterclockwise. The wild part? You’re both right.

The Spinning Dancer is an optical illusion featuring a silhouetted figure that some viewers perceive as spinning clockwise, while others see her spinning counterclockwise, and this ambiguous illusion occurs because the brain lacks sufficient depth cues to determine the figure’s orientation, causing perception to flip between two plausible interpretations. Without enough information to determine which way is “forward” and which is “back,” your brain makes its best guess and commits to an interpretation.

Honestly, this illusion shows that perception isn’t passive. Your brain is actively constructing what you see, and when presented with ambiguity, it picks a story and runs with it.

The Kanizsa Triangle: Seeing What Isn’t There

Three Pac-Man-like shapes arranged in a triangle pattern create something remarkable: you see a bright white triangle that doesn’t actually exist. This illusion, popularized by Italian psychologist Gaetano Kanizsa, reveals how we tend to seek closure in our visual perception, as our brains are trained to fill in the gaps between shapes and lines and perceive blank space as objects even when there aren’t any, and Kanizsa’s triangle is a case in point that visual perception is shaped by experiences and not merely dependent on sensory input.

We not only perceive two triangles, but even interpret the whole configuration as one with clear depth, with the solid white “triangle” in the foreground of another “triangle” which stands bottom up, and to detect and recognize such Gestalts is very important for us, and we feel rewarded when having recognized them as Gestalts despite indeterminate patterns. Your visual system loves creating meaningful wholes from fragmentary information, and this illusion demonstrates that beautifully.

The Café Wall Illusion: Parallel Lines That Aren’t

Rows of staggered black and white tiles create a striking effect: the horizontal lines separating each row appear to slope dramatically. Get a ruler, though, and you’ll discover they’re perfectly parallel. This café wall illusion was named after a tiled wall spotted at a café in Bristol, and it’s all about how our visual system processes luminance contrast and spacing; the staggered black-and-white tiles create false gradients, so your brain “corrects” for a distortion that isn’t really there.

Let’s be real: your brain is constantly making predictions about edges, angles, and alignment. Usually, those predictions serve you well. Sometimes, clever patterns like this one reveal the assumptions baked into your visual processing.

The Ebbinghaus Illusion: Size Is Relative

Two identical circles sit side by side. One is surrounded by large circles; the other by tiny ones. The circle surrounded by large circles looks smaller, while the one ringed by small circles appears bigger. This illusion of relative size perception was discovered by psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, and your brain makes a comparison of relative size based on the surrounding dots.

Context is everything to your brain. It doesn’t just register absolute size; it constantly evaluates objects in relation to their surroundings. This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. Knowing whether something is big or small compared to nearby objects helps you navigate, hunt, and avoid danger. The Ebbinghaus illusion simply exploits this built-in comparison system.

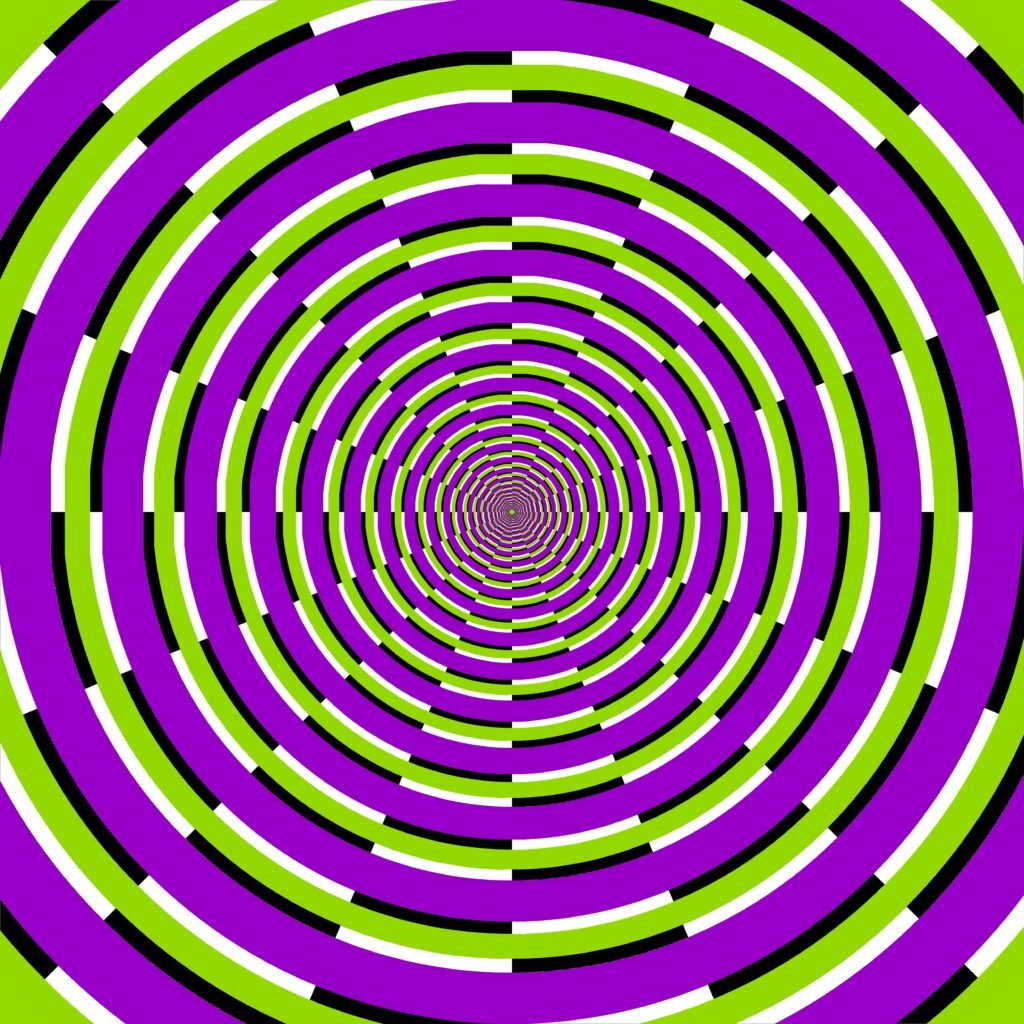

Illusory Motion: Static Images That Seem to Move

You’ve seen those images online: static patterns of colors and shapes that appear to swirl, rotate, or pulse. They’re not animated, yet they seem alive. This optical illusion is a static image which appears to be moving due to the cognitive effects of interacting color contrasts, object shapes, and position.

The perception of motion is caused by the brain’s interpretation of patterns seen outside of the eye’s area of focus, and the illusion depends on a repeating pattern of high contrast, light and dark colors. It’s hard to say for sure what’s happening, yet researchers think fixation jitter (tiny involuntary eye movements) and confused motion detectors in your visual cortex might be responsible. The fact that we don’t fully understand these illusions makes them even more intriguing.

Conclusion: Your Brain Is a Beautiful Mess

Perception is not supposed to be an accurate representation of sensory information; rather, it’s supposed to be an interpretation. Optical illusions aren’t bugs in your visual system. They’re features. Your brain evolved to make rapid judgments, fill in missing information, and construct a coherent experience from incomplete data. Most of the time, this works spectacularly well.

These ten illusions reveal the hidden machinery behind your perception: how context shapes judgment, how neurons adapt and compete, how assumptions about depth and distance guide what you see. Illusions in a scientific context are not mainly created to reveal the failures of our perception or the dysfunctions of our apparatus, but instead point to the specific power of human perception, and the main task of human perception is to amplify and strengthen sensory inputs to be able to perceive, orientate and act very quickly, specifically and efficiently.

Next time you encounter an optical illusion, don’t just marvel at the trick. Think about what it’s teaching you about yourself. What does it feel like when your brain gets caught making an assumption? Pretty fascinating, right?

Hi, I’m Andrew, and I come from India. Experienced content specialist with a passion for writing. My forte includes health and wellness, Travel, Animals, and Nature. A nature nomad, I am obsessed with mountains and love high-altitude trekking. I have been on several Himalayan treks in India including the Everest Base Camp in Nepal, a profound experience.