Look around you for a second. The colors, the shapes, the movement you think you see so clearly? A lot of that is your brain quietly guessing, filling in gaps, and sometimes getting things spectacularly wrong. That’s not a glitch; it’s how you stay sane in a chaotic, overloaded world. But once you start noticing the tricks, it’s hard to shake the feeling that reality is a little less solid than it seemed.

Visual illusions are like cheat codes that let us peek behind the curtain. They expose the shortcuts, assumptions, and hidden rules your brain uses every second just to make sense of life. Some of the illusions below might make lines bend that are perfectly straight, colors appear that aren’t really there, or motion emerge from still images. Each one tells a different story about how your brain builds your version of reality – and just how fragile that version really is.

The Müller-Lyer Illusion: How Context Warps Our Sense of Size

Imagine two simple lines: same length, same color, same everything – except one has arrowheads pointing inward, and the other has arrowheads pointing outward. Almost everyone swears one line is longer, even when careful measurements prove they’re identical. That uncomfortable gap between what you see and what you know is the Müller-Lyer illusion at work. Your brain isn’t “seeing” the line; it’s interpreting it based on the context of those tiny arrows.

Researchers think our visual system is unconsciously treating those arrows like 3D depth cues, a kind of shortcut shaped by living in a world full of corners, edges, and perspective. Lines that look like inside corners (like a room) are processed differently from lines that look like outside edges. In everyday life, this helps you judge distance and size quickly, but the illusion exposes the cost of that speed: your perception is biased, not neutral. Next time you’re sure one object looks bigger than another, it might be the brain’s “helpful” context filter quietly nudging you in the wrong direction.

The Checker Shadow Illusion: When Light Tricks Your Sense of Color

Picture a checkerboard with a cylinder casting a soft shadow across it. One square in the light looks dark gray, and another square in the shadow looks light. If someone told you they’re actually the exact same shade, it feels almost insulting – until you see the colors isolated and your jaw drops. This is the checker shadow illusion, and it brutally exposes how much your brain edits reality before you ever become aware of it.

Your visual system constantly compensates for lighting, which is usually a lifesaver. It tries to figure out: “Is this surface really dark, or just in a shadow?” To do that, it compares nearby shades and applies a kind of automatic correction. In most situations, that lets you recognize objects under different lighting conditions without much effort. But in this illusion, that same correction system backfires, and you end up absolutely certain that two identical colors are completely different. It’s a reminder that you don’t just see colors – you see your brain’s best guess at what the colors should be.

The Ames Room: A Distorted Space That Breaks Your Size Intuition

If you’ve ever seen a video where someone walks from one side of a room to the other and seems to magically grow or shrink, you’ve probably seen an Ames room. At first glance, it looks like a normal rectangular room, but it’s actually a bizarre trapezoid built to perfectly exploit your assumptions about perspective. One corner is much farther away and much lower than it appears, while the other is closer and higher, yet the room is painted and framed so your brain insists it’s all normal.

Your brain relies heavily on the assumption that rooms are box-shaped and corners are right angles. It uses that assumption, plus the apparent size of people in the scene, to estimate their distance and height. In an Ames room, that assumption is dead wrong, but your brain clings to it anyway. The result is that two people of similar height suddenly look wildly different in size just by switching places. Rationally, you know they didn’t shrink or grow in a few steps, but your eyes keep telling a different story – and your brain, stubborn as ever, believes the room over the facts.

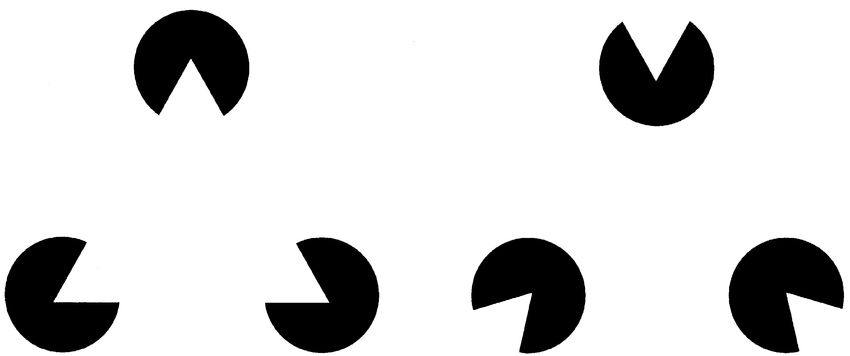

The Kanizsa Triangle: Seeing Shapes That Aren’t Really There

Take three Pac-Man-like circles arranged just so, with a few wedges missing, and most people instantly see a bright white triangle floating on top. The weird part? There is no triangle drawn at all – just gaps and outlines that strongly suggest one. This is the Kanizsa triangle, and it shows how your brain actively hallucinates structure to make sense of fragmented information. You don’t just see what’s there; you see what your brain thinks should be there.

Psychologists call these “illusory contours,” and they pop up all over everyday life. Think of how you can see a familiar object even when part of it is hidden behind something else. Your brain fills in the missing edges so quickly you don’t even notice the guesswork. The Kanizsa triangle simply exaggerates that process in a clean, controlled way. It proves that your brain would rather invent a clear, coherent shape than accept clutter and ambiguity – even if that means seeing a triangle that technically does not exist on the page.

The Rubin Vase: One Image, Two Realities Competing for Control

Stare at a classic black-and-white illusion: in the center, there’s a white vase; in the surrounding black space, two faces in profile. But you can’t see both interpretations fully at the same time. Your perception flips: vase… faces… vase… faces. This is the Rubin vase, and it reveals how your brain constantly decides what’s “figure” (the main object) and what’s “background” (everything else). That decision is not neutral – it completely changes what you think you’re looking at.

Your brain likes stable, meaningful objects, and it struggles when two equally plausible interpretations fight for dominance. So it picks one, then the other, in a kind of perceptual tug-of-war. What’s striking is that the physical image never changes; only your interpretation does. This shows that reality, at least visually, is partly a mental negotiation. Two people can literally look at the same thing and “see” different objects, and neither is wrong. The Rubin vase makes that uncomfortable truth impossible to ignore.

The Motion Aftereffect: Why the World “Moves” After You Stop Watching

You’ve probably had this experience: after staring at a waterfall or scrolling on your phone for a long time, you look away and the world seems to drift or slide in the opposite direction. That eerie sensation is called the motion aftereffect. It happens because your brain has special neurons that respond to motion in particular directions, and when they’re over-stimulated, they adapt and temporarily dial down their sensitivity.

When you stop looking at the moving pattern, the adapted neurons are “quieter” than the others, and your brain interprets that imbalance as motion in the opposite direction. The image in front of you is perfectly still, but your motion-processing system insists it’s moving. This is not just a cute trick; it shows that even something as basic as movement is a constructed perception, not a direct recording. Your brain is constantly recalibrating to stay responsive, and that adaptive strength is exactly what gives rise to the illusion.

The Color Afterimage: When Staring Too Long Creates Phantom Hues

Try this simple experiment: stare at a bright red square for a while, then quickly look at a blank white wall. Many people suddenly see a soft greenish patch floating where the red used to be. Nothing is on the wall, of course; it’s all happening in your visual system. This is a color afterimage, and it’s rooted in how your eyes and brain handle color through opponent pairs like red–green and blue–yellow.

When you stare at a strong color, the cells that respond to that color become temporarily less responsive. Once you shift to a neutral surface, like white, the opposing cells fire more strongly by comparison, and your brain interprets that as the complementary color. You’re essentially seeing the “shadow” of what you just looked at, painted not in darkness but in its opposite hue. That fleeting ghost of color is a reminder that what you see depends on what you saw a moment ago, not just what’s in front of you right now.

The Blind Spot Fill-In: How Your Brain Hides Missing Information

Every one of us has a literal hole in our vision where the optic nerve exits the back of the eye. No light-sensitive cells sit there, so technically you should see a dark gap in your visual field. You don’t. Instead, your brain quietly patches the hole with surrounding colors, textures, and patterns so convincingly that you never notice. This isn’t a rare glitch – it’s happening all the time, for everyone, in both eyes.

You can find your blind spot with simple tests: cover one eye, focus on a dot, and move a nearby symbol until it seems to vanish. When it disappears, your brain doesn’t show you a black void; it shows you background. That automatic fill-in process is incredibly useful in daily life, where gaps and occlusions are everywhere. But it also makes it clear that your experience of a continuous, seamless world is partly a clever illusion. You literally never see the full picture, yet you feel like you do.

The Ponzo Illusion: When Perspective Lines Rewrite Size

In the Ponzo illusion, two identical horizontal bars are placed between converging lines that look like train tracks or a road disappearing into the distance. The bar near the “farther” end looks longer than the one near the “closer” end, even though they are the same length. Your brain has been trained by years of navigating 3D space to treat converging lines as depth cues. When it sees those lines, it instantly shifts into perspective mode.

Once your brain decides one bar is farther away in 3D space, it expects that a more distant object casting the same image size on your retina must actually be larger. So it inflates your perception of its size to match that assumption. The illusion exposes how deeply your sense of size is tied to your sense of distance. You are not measuring objects with an internal ruler; you are unconsciously running a complex depth-and-context calculation that usually works – until an image like this hijacks it.

The Hollow-Face Illusion: When Knowledge Loses to Expectation

The hollow-face illusion uses a concave mask – think of the inside of a face mold. Even when you know it’s hollow, most people still see it as a normal, convex face turning to follow them as they move. That creepy effect happens because your brain has such a strong prior expectation that faces are outward, not inward. It basically refuses to believe the raw depth cues your eyes are sending.

Faces are incredibly important for social life, so your brain gives them special treatment, using powerful assumptions to keep them stable and recognizable under changing lighting and angles. In the hollow-face illusion, those assumptions completely override the physical reality of the object. This is one of those experiences that can feel almost unsettling in person, because you can intellectually know it’s wrong and still feel it’s right. It’s a blunt reminder that what feels “obvious” and “real” can be the product of stubborn expectations rather than accurate data.

Illusions as Windows Into Our Constructed World

All these illusions point to the same deeply uncomfortable but strangely beautiful idea: you don’t see the world as it is, you see the world as your brain needs it to be. It edits, compresses, fills in, exaggerates, and sometimes outright invents in the name of speed and survival. Most of the time, those shortcuts help you move through life without being paralyzed by detail, but illusions expose the hidden machinery shaping every moment of your experience.

Once you realize that, everyday perception starts to feel less like a camera feed and more like a live, improvised performance directed by your brain. Lines that bend, colors that shift, motion that appears from nowhere – they are all clues that your reality is a carefully curated story, not a raw download. The next time you catch your eyes “lying” to you, maybe the more honest question is this: how often are they bending the truth in ways you simply never notice?