Some of the most astonishing landscapes on Earth are invisible to the naked eye, hiding in the weave of your bedsheets, the surface of your teeth, even inside a single grain of sand. Under a good microscope, the familiar world fractures into alien terrain: forests made of mold, crystal cities, and living “machines” that look more like art than biology. This article dives into ten of these microscopic wonders, not as abstract textbook diagrams but as real, physical places and creatures shaping your everyday life in ways you almost never think about. By the end, brushing your teeth, scrolling your phone, or standing in the rain may feel completely different. Let’s shrink down and meet the worlds that were always there, just too small to see.

The Crystal Cathedrals Growing Inside Everyday Salt

On your kitchen table, table salt looks boring: tiny white grains, identical and lifeless. Under a microscope, those same grains become sharp-edged cubes, stacked like miniature skyscrapers, with smooth faces and almost impossibly perfect angles. Each grain is a sodium chloride crystal, its atoms arranged in a repeating lattice that gives it that classic cube shape. When salt solutions evaporate, new crystals sprout from old ones, creating branching structures that look like frozen trees or glass cathedrals.

In nature, similar salt crystals form in dried-up lakes and coastal flats, where they can link together into complex, interlocking patterns. The same basic physics that shapes a pinch of table salt also sculpts vast salt pans in deserts around the world. It’s a reminder that geological processes do not suddenly start at the scale of cliffs and canyons; they are already at work in your soup bowl. The hidden geometry resting in your saltshaker is a quiet, crystalline echo of entire landscapes.

Diatoms: Glass-Walled Micro-Architects of the Oceans

Diatoms are microscopic algae that live in oceans, lakes, and even damp soil, and they might be the most exquisite “architecture” nature produces. Each diatom cell builds a shell made of silica, essentially glass, patterned with intricate pores, ridges, and ribs that look like designer jewelry under an electron microscope. These glass walls are not just pretty; they regulate how light enters the cell and help the diatom stay afloat at the right depth. Some species resemble delicate gears, others tiny petri dishes, and others still a fusion of snowflakes and stained glass windows.

Despite their delicate appearance, diatoms are ecological heavyweights, contributing a substantial portion of the oxygen you breathe and locking away carbon in the deep sea when they die and sink. Their fossilized remains form deposits known as diatomaceous earth, used in everything from filtration systems to gentle abrasives in toothpaste. Scientists study the nanostructure of diatom shells for inspiration in designing advanced materials and photonic devices. The next time you look out over the ocean, it is worth remembering that vast swarms of invisible glass-walled engineers are quietly running much of the planet’s carbon and oxygen cycles.

Tardigrades: Near-Invincible Bears in a Drop of Moss Water

Tardigrades, often nicknamed water bears, are among the most charismatic microscopic creatures, looking like eight-legged stuffed animals wandering through films of water. At a fraction of a millimeter long, they live on wet moss, in soil, and in both freshwater and marine environments, grazing on algae or other small organisms. What made them famous, though, is their ability to survive extremes that would kill almost anything else: intense radiation, near-total dehydration, extreme cold, and very low pressures. When conditions turn hostile, they curl into a desiccated state called a tun, shutting down most biological activity until water returns.

Researchers have sent tardigrades into orbit and through conditions mimicking outer space, and some individuals revived back on Earth, adding to their almost mythic reputation. They pull off this survival trick using specialized proteins and sugars that protect their cells and DNA from damage when water is removed. To be clear, they are not truly indestructible, but compared to most animal cells, their resilience is extraordinary. The existence of such hardy micro-animals forces scientists to rethink where life might survive, from icy moons to the edges of our atmosphere, and how robust life can be in the face of catastrophe.

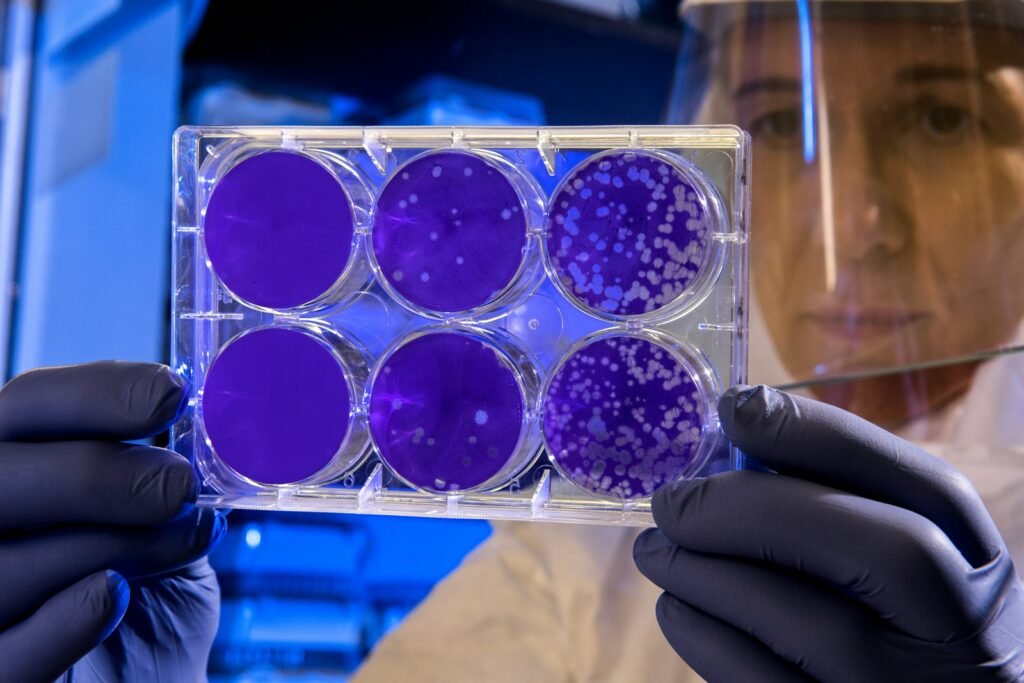

Bacterial Biofilms: Slimy Cities on Your Teeth and Pipes

Every morning, the fuzzy coating you feel on your teeth before brushing is a living city of bacteria known as a biofilm. Instead of floating freely, these microbes attach to surfaces and secrete a sticky matrix that glues them together, creating something like a high-rise complex with micro-channels and neighborhoods. Within that slimy structure, different species specialize and cooperate, swapping nutrients and chemical signals to coordinate their behavior. Under a microscope, a dental biofilm looks like stacked clusters and towers, riddled with tiny water channels that function a bit like plumbing for the microbial community.

Biofilms are not limited to mouths; they form on ship hulls, medical implants, water pipes, and river rocks. This communal lifestyle makes bacteria more resistant to antibiotics and disinfectants, turning what seems like a harmless layer of slime into a serious engineering and medical challenge. Hospitals, for example, have to contend with biofilms in catheters and tubing that standard cleaning cannot easily remove. The idea of microbes building cities may sound whimsical, but those microscopic metropolises have concrete impacts on human health, infrastructure, and industry.

Dust Mites: Microscopic Grazers in Your Mattress Ecosystem

If you could shrink yourself down and walk across your mattress, you would be walking through a dense, fibrous jungle of fabric, human skin flakes, and dust. In that tangle live dust mites, tiny arachnids that feed primarily on shed human and animal skin cells. Under magnification, they look like translucent, plump-bodied creatures with stubby legs and clawed tips, moving slowly between fibers. They are not parasites and do not bite humans, but their droppings and body fragments can trigger allergies and asthma in sensitive people.

Dust mites thrive in warm, humid environments, which is why bedding, upholstered furniture, and carpets are prime real estate. From a microscopic viewpoint, a single pillow becomes an entire landscape of caves and tunnels, with mites navigating in search of food and moisture. Regular washing of bedding in hot water and reducing humidity indoors can lower their numbers, but they are almost impossible to eliminate completely. It can be unsettling to realize that your bed is an entire ecosystem, yet it also underscores that human life is always intertwined with unseen communities of other organisms.

Pollen Grains: Spiky, Sculpted Capsules Built for Travel

Pollen often shows up in our lives as a nuisance, the invisible culprit behind itchy eyes and springtime sneezing. Under a microscope, though, pollen grains transform into an astonishing gallery of tiny sculptures, each plant species crafting its own distinctive shape. Some grains are spherical and smooth, while others bristle with spikes, grooves, or intricate patterns that resemble carved armor. These surface structures are not mere decoration; they help pollen stick to pollinators’ bodies or catch the wind more effectively.

Because pollen walls are tough and chemically resistant, grains can be preserved for thousands of years in sediments and ice cores. Palynologists, scientists who study pollen, use these microscopic time capsules to reconstruct ancient climates and vegetation, tracking how forests expanded or retreated and how agriculture spread. Forensic investigators have even used unique pollen signatures to help link objects or people to particular locations. The next time a weather report warns of high pollen counts, it is worth imagining not a vague cloud of irritants but a blizzard of exquisitely designed, species-specific capsules moving through the air.

Radiolarians: Glassy Skeletons Floating in the Twilight Sea

Drifting in the open ocean are radiolarians, single-celled organisms that build elaborate internal skeletons from silica. Viewed through a microscope, these skeletons are some of the most astonishing natural designs known: spheres pierced by delicate spines, geometric cages of intersecting rods, and starburst structures that seem too precise to be living. The intricate shapes help support the cell and can influence how the organism drifts or sinks in the water column. Many radiolarians host symbiotic algae inside their bodies, turning themselves into tiny solar-powered platforms.

Over geological time, the remains of these organisms rain down onto the seafloor, forming thick layers of siliceous ooze that can eventually become rock. These deposits act as a record of past ocean conditions, including temperature and nutrient levels, offering clues about Earth’s climate history. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, their skeletons inspired artists, architects, and designers interested in the overlap between biology and geometry. Radiolarians show that even in the dim, open waters far from coastlines, the microscopic world builds structures that rival the most complex man-made designs.

Microfossils in Chalk: Ancient Shells Hidden in Classroom Dust

A stick of natural chalk may look like an unremarkable white cylinder, but its powder is packed with the remains of countless microscopic organisms. Much of traditional chalk is formed from the shells of coccolithophores, single-celled algae that encase themselves in overlapping calcium carbonate plates. Under magnification, these plates form intricate rosettes or shield-like discs that fit together around the cell like armor. When coccolithophores die, their shells rain down and accumulate on the seafloor, eventually forming chalk and limestone over millions of years.

The famous white cliffs in some coastal regions are essentially massive archives of these tiny skeletons, stacked layer upon layer from ancient seas. By studying the chemistry and species composition of coccolith microfossils, scientists can reconstruct past ocean temperatures and acidity. That makes a thin smear of chalk dust on a blackboard, or a crumb of soft limestone, a direct physical connection to vanished oceans and long-extinct plankton communities. What looks like featureless white rock at our scale is, under the microscope, a densely packed graveyard of miniature shells with a detailed environmental story to tell.

Cellular Highways: Molecular Motors Marching Inside Your Cells

Not all microscopic wonders are separate organisms; some are processes unfolding constantly inside your own body. Within each of your cells, proteins called molecular motors haul cargo along protein filaments, turning chemical energy into directed motion. Under high-resolution imaging, these motors, such as kinesin, appear like tiny walkers stepping along a track, dragging vesicles or organelles behind them. The filaments themselves, made of actin or microtubules, form a dynamic network often described as the cell’s cytoskeleton, yet it is closer to a constantly shifting road system.

These molecular deliveries are not optional. They position chromosomes during cell division, move neurotransmitter-filled packets to nerve endings, and help immune cells reorganize themselves to attack pathogens. Disruptions in these microscopic transport systems are linked to a range of diseases, including some neurodegenerative conditions. When you move your hand, think a thought, or heal a cut, armies of invisible molecular machines are already doing their work beneath your awareness. It makes everyday actions feel less trivial when you remember they rely on logistics chains more complex than many human-built supply networks.

What the Microscopic World Reveals About How We See Reality

Viewed together, these ten microscopic wonders expose a deep bias in how we understand reality: we trust what we can see with unaided eyes, and quietly ignore everything smaller. Before modern microscopy, salt was just seasoning, chalk just rock, and pond water just water. Now we know each is crowded with structures, histories, and organisms, many of which have far-reaching effects on global climate, human health, and even technology. Scientific advances did not create these worlds; they simply widened our window enough to notice them.

Compared with early microscopes that produced blurry images and distortions, contemporary instruments reveal atomic lattices, three-dimensional cell structures, and even real-time molecular motions. That leap in clarity has shifted many fields, from medicine to materials science, by grounding theories in directly observed microstructures rather than abstract guesses. Yet there is still a cultural lag, where everyday thinking treats microbes, cells, and crystals as background details rather than central characters. Recognizing that our bodies, homes, and landscapes are built from and inhabited by intricate micro-worlds pushes us away from the comforting illusion of simplicity. It nudges us toward a more layered, honest picture of reality, where the unseen is not secondary but foundational.

How Looking Closer Changes What We Do Next

Once you start picturing tardigrades in moss, biofilms on pipes, and pollen sculptures on the wind, it becomes harder to move through the world on autopilot. You might rinse your reusable water bottle more carefully, not out of anxiety but because you now know how enthusiastically bacteria can colonize rough surfaces. You might actually enjoy looking at high-magnification photos from public science collections, treating them the way others treat landscape photography. Supporting local science museums, citizen-science projects that track microbes, or school programs that put microscopes in kids’ hands becomes less abstract and more like opening doors to new worlds.

Even simple acts can deepen your connection to the miniature realm: collecting a drop of pond water to view at a community lab, using an inexpensive clip-on phone microscope, or paying closer attention to how dust, mold, and water behave at small scales. None of this requires becoming a professional scientist; it just means letting curiosity win a little more often. The most important shift may be internal: accepting that our everyday environment is richer, stranger, and more intertwined than it first appears. The next time sunlight catches dust motes in the air or you sprinkle salt on your dinner, will you picture the invisible universes that come along for the ride?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.