Have you ever wondered which creatures hold the keys to unlocking the mysteries of how life transforms over millions of years? Evolution isn’t just an abstract concept buried in textbooks. It’s written into the bones, wings, fins, and DNA of animals that walked, swam, and flew across our planet. Some of these creatures became so pivotal to science that they fundamentally reshaped how we think about the origin of species and the intricate dance of natural selection.

What makes an animal evolutionary gold? Sometimes it’s the perfect timing of its discovery, appearing just when scientists needed proof. Other times it’s the blend of features, a living puzzle piece connecting two vastly different groups. These animals don’t just tell stories. They rewrite entire chapters of life’s history. Let’s dive in and meet the remarkable creatures that changed everything.

Darwin’s Finches: The Birds That Started It All

Picture yourself on a remote volcanic island in the Pacific, watching small brown birds hop between cacti and lava rocks. You might not think much of them at first glance. Yet these unassuming finches on the Galápagos Islands became the poster children for evolution itself. On the Galápagos Islands, Darwin observed several species of finches with unique beak shapes, and he noted these finches closely resembled another finch species on the mainland of South America, forming a graded series of beak sizes and shapes.

Today, Darwin’s finches are the classic example of adaptive radiation, the evolution of groups of plants or animals into different species adapted to specific ecological niches. What’s truly fascinating is how quickly these changes happen. Peter and Rosemary Grant and their colleagues have studied Galápagos finch populations every year since 1976 and have demonstrated that surviving large-billed birds tend to produce offspring with larger bills, so the selection leads to evolution of bill size. During droughts, when only large, tough seeds remain, big-beaked finches thrive. When rains return and soft seeds flourish, smaller beaks make a comeback. It’s evolution in fast-forward, happening right before our eyes.

The Peppered Moth: Evolution in the Smoke

Sometimes evolution doesn’t require millions of years. Sometimes all it takes is a century of coal smoke and polluted skies. The evolution of the peppered moth is an evolutionary instance of directional colour change in the moth population as a consequence of air pollution during the Industrial Revolution, with the frequency of dark-coloured moths increasing at that time.

Here’s the thing about the peppered moth story that makes it so compelling. In 1848 a dark melanic morph of the peppered moth was first noticed in Manchester, and by 1898 this dark morph outnumbered the light-coloured morph by 99 to 1. The light-colored moths, once perfectly camouflaged against lichen-covered trees, became sitting ducks for hungry birds when soot blackened the bark. The rare dark moths suddenly had the advantage. Then, when environmental laws cleaned up the air decades later, the light moths returned to dominance. Industrial melanism in the peppered moth is still one of the clearest and most easily understood examples of Darwinian evolution in action, proving that natural selection responds to environmental change in real time.

Tiktaalik: The Fish That Crawled

Imagine a world where no vertebrate had ever set foot on land. Every backboned animal lived underwater, finned and gilled. How did that change? Enter Tiktaalik, a fossil that looks like nature couldn’t decide whether to make a fish or a four-legged animal. Tiktaalik is a monospecific genus of extinct sarcopterygian from the late Devonian Period, about 375 million years ago, having many features akin to those of tetrapods, and it was unearthed in Arctic Canada, complete with scales and gills but also with a triangular, flattened head and unusual, cleaver-shaped fins.

What makes Tiktaalik remarkable isn’t just what it looked like. It’s where it sits in the story. Its fins have thin ray bones for paddling like most fish, but they also have sturdy interior bones that would have allowed Tiktaalik to prop itself up in shallow water and use its limbs for support as most four-legged animals do. You’re looking at an animal caught between two worlds, neither fully fish nor fully landlubber. Tiktaalik was believed to be the best representative of the alleged transitional species scientists needed to prove evolution, and this discovery was crucial because it changed the public’s understanding of tetrapod anatomy and evolutionary biology as a whole. Though debates continue about its exact place in our family tree, Tiktaalik gave us a window into one of life’s greatest transitions.

African Cichlid Fish: Speciation on Speed

If you want to witness evolution running at breakneck speed, look no further than the Great Lakes of East Africa. With approximately 2,000 known species, hundreds of which coexist in individual African lakes, cichlid fish are amongst the most striking examples of adaptive radiation, and the largest radiations in Lakes Victoria, Malawi and Tanganyika took no more than 15,000 to 100,000 years for Victoria and less than 5 million years for Malawi. Think about that for a moment. Hundreds of distinct species, each with unique colors, behaviors, and ecological roles, all arising in geological eyeblinks.

These fish don’t just evolve fast. They’ve essentially become living laboratories for studying how new species form. Between 1000 and 2000 speciation events occurred in the past 5 million years alone, and the large number of independent replicate radiations, their phenotypic diversity, their wide range of ages, and the presence of many more instances where cichlids failed to radiate make this a uniquely powerful model system. Some species evolved to crush snails, others to scrape algae, and still others developed bizarre jaw structures to steal scales from other fish. The creativity of evolution is on full display in these lakes, showing how quickly life can diversify when opportunity knocks.

Archaeopteryx: The Dinosaur with Feathers

Few fossils have caused as much excitement, controversy, and wonder as Archaeopteryx. The type specimen of Archaeopteryx was discovered just two years after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, and Archaeopteryx seemed to confirm Darwin’s theories and has since become a key piece of evidence for the origin of birds, the transitional fossils debate, and confirmation of evolution. Timing, as they say, is everything.

What exactly made this fossil so special? Most of the specimens of Archaeopteryx come from the Solnhofen limestone in Bavaria, southern Germany, and date to approximately 150.8 to 148.5 million years ago. This creature had teeth, a long bony tail, and clawed fingers like a dinosaur, yet it also possessed wings and flight feathers like a bird. Only the identification of feathers on the first known specimens indicated that the animal was a bird, and unlike living birds, Archaeopteryx had well-developed teeth and a long well-developed tail similar to those of smaller dinosaurs. It was the perfect intermediate, a snapshot frozen in limestone showing exactly how dinosaurs could transform into birds. No wonder it’s remained iconic for over 160 years.

Whales: From Land Back to Sea

Here’s something that blows people’s minds. Whales, those magnificent ocean giants, descended from land-dwelling mammals that walked on four legs. The fossil record has revealed a stunning series of transitional forms showing this remarkable evolutionary journey in reverse. Early whale ancestors like Pakicetus had legs and lived near water roughly 50 million years ago, while later forms like Ambulocetus could both walk and swim.

These creatures show progressive adaptations to aquatic life. Nostrils migrated from the front of the snout toward the top of the head, becoming the blowhole. Hind limbs shrank and eventually disappeared internally. Bodies became streamlined. Tails developed powerful flukes for swimming. It’s one of the best-documented examples of a major evolutionary transition, with fossils capturing nearly every step of the process. The ancestors of whales didn’t suddenly leap into the ocean. They waded in gradually over millions of years, and the evidence is written in stone.

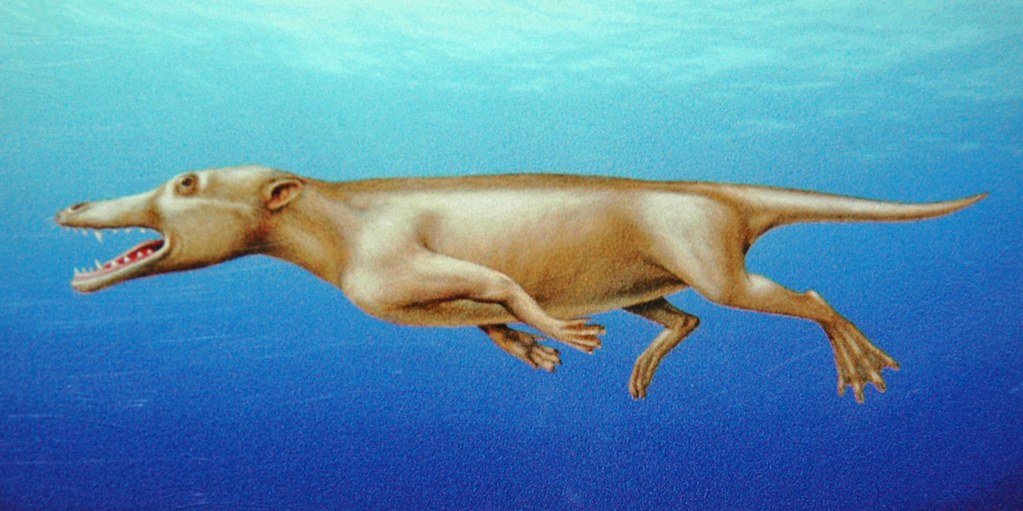

Ambulocetus: The Walking Whale

Speaking of whale evolution, let’s talk about one of the strangest creatures you’ve probably never heard of. Ambulocetus, whose name literally means “walking whale,” lived about 49 million years ago in what’s now Pakistan. This animal looked like someone had crossed a crocodile with a seal and given it the attitude of a wolf.

Ambulocetus had powerful legs that could support its weight on land, but its feet were webbed and its tail was strong for swimming. Its eyes sat on top of its head like a crocodile’s, perfect for lurking in shallow water. It probably hunted like a modern crocodile too, ambushing prey from the water’s edge. This wasn’t quite a whale and wasn’t quite a land mammal. It was beautifully, awkwardly in between. These kinds of fossils are precious because they show evolution doesn’t happen in neat jumps. It happens in awkward, experimental stages where animals are trying out new lifestyles while still keeping one foot, or fin, in their ancestral world.

Horses: A Complete Evolutionary Sequence

If you’ve ever visited a natural history museum, you’ve probably seen the classic horse evolution display. It starts with a tiny, dog-sized animal with multiple toes and ends with the powerful, single-toed horse we know today. Horse evolution spans roughly 55 million years, and we have an remarkably complete fossil record documenting the changes.

The earliest horse ancestor, Eohippus (also called Hyracotherium), stood only about a foot tall and had four toes on its front feet and three on its back feet. It lived in forests and browsed on soft leaves. Over millions of years, as grasslands spread and forests retreated, horses gradually became larger, their teeth adapted for grinding tough grasses, and their toes reduced until only the middle toe remained, forming a hoof. This wasn’t a straight line of progress. It was a branching tree with many experimental forms, most of which went extinct. But the overall trend toward larger size, longer legs, and teeth suited for grazing shows how environments shape evolution over deep time.

Homo naledi: Rewriting Human Origins

Our own evolutionary story keeps getting more complicated and fascinating. In 2013, cavers exploring South Africa’s Rising Star Cave system stumbled upon a chamber filled with over 1,500 fossil bones from at least 15 individuals. They belonged to a previously unknown human relative named Homo naledi. This species is a wonderful mosaic of primitive and modern traits.

Homo naledi had a small brain, about the size of an orange, similar to much older human ancestors. Its shoulders and curved fingers suggest it was good at climbing. Yet its feet, legs, and hands show advanced features similar to modern humans. Most puzzling of all, the fossils may be only 200,000 to 300,000 years old, meaning this small-brained human relative lived at the same time as Homo sapiens. This discovery challenged the old idea that human evolution was a simple ladder from primitive to advanced. Instead, it’s a tangled bush with multiple species coexisting, each adapted to their own niche. Some had big brains, some had small brains, and they all called Africa home at the same time.

Basilosaurus: The Serpent Whale

Let’s return to whale evolution one more time with one of the most bizarre creatures to ever swim the ancient seas. Basilosaurus, despite its name suggesting a reptile, was actually a whale. But what a whale it was. Living about 40 to 34 million years ago, Basilosaurus stretched up to 60 feet long with a serpentine body that looked more like a sea monster than a modern whale.

Here’s the kicker: this fully aquatic whale still had tiny, vestigial hind legs. They were too small to support the animal’s weight or help with swimming, just little reminders of its four-legged ancestors. These useless legs are evolutionary leftovers, proof that Basilosaurus descended from land mammals. Why did it keep them? Evolution doesn’t plan ahead or clean up perfectly. If a feature doesn’t actively harm an animal’s survival, it might just stick around as biological baggage. Those little legs tell a story louder than words ever could. They whisper that this ocean giant once had ancestors that walked on land, and that transformation from terrestrial to marine happened gradually enough to leave traces behind.

Conclusion: Evolution’s Living Library

These ten animals represent just a fraction of the incredible diversity that has taught us how evolution works. From finches changing beak sizes in response to droughts, to moths shifting color with industrial pollution, to fossils bridging the gap between fish and land animals, or dinosaurs and birds, each discovery has added another piece to the puzzle. They’ve shown us that evolution isn’t just a theory. It’s an observable process happening all around us, documented in both living populations and ancient stones.

What’s remarkable is how much we’ve learned and how much still remains mysterious. Every new fossil, every genetic study, every long-term observation of wild populations adds depth to our understanding. These animals didn’t just change science. They changed how we see ourselves and our place in the vast, interconnected web of life. We’re part of the same story, shaped by the same forces that molded finches’ beaks and grew legs into flippers.

Did you find any of these creatures as surprising as I do? The natural world has been running experiments in adaptation and survival for billions of years, and we’re only beginning to read the results.

Hi, I’m Andrew, and I come from India. Experienced content specialist with a passion for writing. My forte includes health and wellness, Travel, Animals, and Nature. A nature nomad, I am obsessed with mountains and love high-altitude trekking. I have been on several Himalayan treks in India including the Everest Base Camp in Nepal, a profound experience.