History loves to tell stories of heroic discoveries and brilliant breakthroughs. But if you look a little closer, some of the biggest turning points in human history were shaped not by genius working perfectly, but by science getting things wrong in surprising, sometimes heartbreaking ways. Miscalculations, wrong theories, flawed data, and blind trust in “experts” have changed borders, cost lives, crashed economies, and even started wars.

What makes these stories so gripping is not just the drama, but the realization that people at the time genuinely believed they were acting on solid knowledge. They trusted the best science available – and that “best science” was sometimes deeply flawed. In a strange way, that makes the past feel painfully familiar. We still wrestle with uncertainty, with experts disagreeing, and with the risk that today’s confident answers might become tomorrow’s cautionary tales. Let’s walk through ten moments when scientific errors didn’t just stay in the lab – they rewrote history.

The “Unsinkable” Titanic and the Misjudged Iceberg Risk

Imagine boarding a ship that newspapers and engineers alike called practically unsinkable, only to learn later that the confidence was built on flawed assumptions and incomplete science. The Titanic story is usually told as one of human arrogance, but under the surface it is also a story of mistaken beliefs about materials, safety design, and ocean hazards. Naval engineers overestimated how well the ship’s watertight compartments would work, assuming that flooding could be neatly contained and controlled.

On top of that, the scientific understanding and communication of iceberg risk in the North Atlantic was rudimentary and badly organized. Shipping routes were not adjusted as aggressively as they should have been, and the speed of the Titanic through known icy waters reflected a belief that the danger was manageable with simple vigilance. Metallurgical studies done decades later showed that the ship’s steel and rivets were more brittle in the cold than designers truly appreciated at the time. That mix of overconfidence in engineering and underestimation of nature’s forces turned one flawed scientific picture into one of the most tragic maritime disasters in history.

Medicine’s Deadly Misstep: Bloodletting and George Washington’s Final Illness

For centuries, medical “science” confidently taught that the body’s health depended on balancing four humors, and that removing blood could cure fever, infections, and all sorts of ailments. By the late eighteenth century, bloodletting was still standard practice, not fringe quackery, and some of the most respected physicians trusted it. When George Washington fell seriously ill in December 1799, he was treated by doctors who believed they were applying the best science available.

They removed an enormous amount of his blood over a short period, far more than a modern doctor would consider safe under almost any circumstances. Today, with a better understanding of circulation, infection, and fluid balance, it’s hard not to see that treatment as catastrophic. While historians debate how much bloodletting alone contributed to his death, the consensus is that the medical theory behind it was fundamentally wrong and likely harmful. It is a brutal reminder that confident science can be deadly when it is built on flawed models of how the body works.

The Cholera Misconception: How Bad Germ Theory Delayed Life-Saving Change

When cholera tore through European cities in the nineteenth century, leaving streets lined with the dead, most experts insisted the disease spread through foul air, or “miasma.” This theory guided policy: officials focused on smells instead of sewage, on ventilation instead of contaminated water. It seemed logical at the time, because bad smells and illness often appeared together, but correlation was mistaken for cause, and the consequences were devastating.

In London, for example, authorities resisted the idea that drinking water was to blame, even when evidence began to mount. Early investigators who linked cholera to water sources were often ignored or ridiculed, because they clashed with the dominant scientific view. This delay meant that cities were slow to overhaul sewage systems and protect drinking water. In practical terms, a wrong theory about disease transmission kept lethal infrastructure in place, letting wave after wave of cholera claim lives that might have been saved if officials had trusted the emerging, more accurate science sooner.

The “War of the Worlds” That Never Was: Mars, Canals, and Misread Telescopes

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many educated people genuinely believed Mars might be home to intelligent life. Astronomers using relatively crude telescopes misinterpreted vague surface markings as straight lines, which some mapped as engineered “canals.” This was not fringe speculation; it was presented as serious science, influenced by optical limitations and human tendency to see patterns where none exist.

While no actual war ever started over Martians, these scientific errors shaped public imagination, science fiction, and even how governments thought about space. The belief in Martian civilizations fueled both fear and excitement, influencing culture and even early space policy discussions. Once better telescopes and space probes revealed Mars as cold, barren, and canal-free, the grand theories collapsed. But for decades, mistaken observations and overconfident interpretations let a mirage of alien civilization shape how humanity viewed its place in the universe.

Race, Eugenics, and the Misuse of Genetics

Few scientific errors have been as poisonous as the belief that complex human traits like intelligence, morality, or “worth” could be ranked cleanly by race and bloodline. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, emerging ideas from biology and heredity were twisted into eugenics, a movement that claimed it was scientifically necessary to control who could have children. Many governments adopted policies based on bad science, faulty statistics, and deeply biased assumptions.

In places like the United States and parts of Europe, forced sterilization laws and immigration restrictions were justified using charts, measurements, and pseudo-rigorous studies that have since been thoroughly discredited. These errors were not harmless mistakes; they empowered discrimination and gave moral cover to horrific abuses, including some of the ideology that fed into Nazi policies later on. The tragedy is that science, which can be a powerful tool for understanding shared humanity, was instead used as a weapon because its methods were misapplied and its findings distorted.

The Y2K Panic: Overestimated Risk, Underappreciated Reality

As the year 2000 approached, a massive global anxiety built around a computer bug now known simply as Y2K. Many experts warned that computer systems would fail when internal clocks rolled from 1999 to 2000, because early software often used only two digits for the year. Some predictions painted borderline apocalyptic scenarios – planes falling from the sky, power grids collapsing, banking locking up worldwide. Governments spent huge sums preparing for a technological catastrophe.

When midnight came and went with only minor glitches, many people laughed it off as a giant overreaction, a scientific and technical error in judgment. The truth is more complicated: the initial risk assessments did sometimes exaggerate the scale of likely damage, but the intense global preparation also fixed a lot of genuine vulnerabilities in advance. Still, the way estimates of risk were communicated to the public was often alarmist and oversimplified, turning nuanced technical uncertainty into near-certainties of disaster. It stands as an example of how misjudged modeling and poor communication around science can reshape policy and public trust, even when the underlying problem is partly real.

The Iraq War and Misinterpreted Scientific Intelligence on Weapons

In the early 2000s, one of the most consequential geopolitical decisions of the modern era – the invasion of Iraq – was heavily justified using technical “evidence” about weapons of mass destruction. Intelligence agencies relied on satellite images, chemical analysis, alleged lab equipment, and defectors’ stories, all interpreted through complex scientific and technical frameworks. Yet much of that evidence was weak, misread, or taken far beyond what the data actually supported.

Some of the supposedly solid scientific conclusions about chemical and biological weapons labs, for example, turned out to be wrong when inspected on the ground. Assumptions filled in where hard proof was lacking, and political pressure amplified the most alarming interpretations. This is not just a story of politics; it is also a story of how scientific and technical intelligence, when stretched or misapplied, can help trigger a war that reshapes an entire region. The costs in lives, stability, and trust were enormous, and the episode remains a harsh lesson in how catastrophic scientific and analytical errors can become once they enter the halls of power.

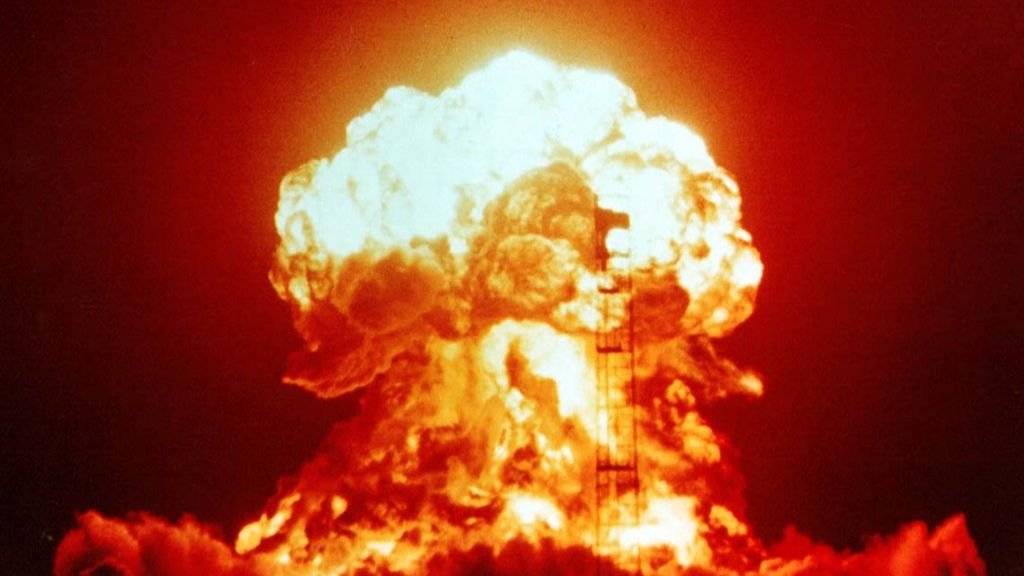

Radiation, Nuclear Testing, and Underestimated Fallout

When nuclear weapons were first developed and tested, even top scientists did not fully understand how far radioactive fallout would spread or how long it would remain dangerous. Early test planners made optimistic assumptions about wind patterns, dispersion, and safe distances. In several tests during the mid-twentieth century, local populations, workers, and even soldiers were exposed to far higher levels of radiation than expected because models were incomplete or wrong.

In some regions downwind of test sites, cancer rates and other health problems later spiked, and governments were forced to confront the gap between their earlier reassurances and grim reality. The science of radiation risk was evolving rapidly, but for too long, uncertainty was brushed aside or minimized. That underestimation influenced policy, from continued atmospheric testing to slow compensation programs for affected communities. History here hinges on miscalculated doses, flawed assumptions, and an overconfident belief that models were solid enough to gamble people’s lives on.

Lead in Gasoline and Paint: A Public Health Disaster Hidden by Bad Science

For much of the twentieth century, lead was added to gasoline to improve engine performance and used widely in paints, even as evidence quietly grew that it was toxic, especially to children. Industry-backed scientists produced reassuring studies that downplayed the risks, using flawed methods, selective data, and misleading comparisons. For years, these distorted findings helped delay regulations, even while independent researchers were raising alarm bells about brain damage and long-term developmental harm.

The scale of the mistake is hard to overstate. Entire generations of children were exposed to levels of lead that we now know can lower cognitive ability, increase behavioral problems, and contribute to social challenges. Urban neighborhoods, in particular, suffered disproportionately. This was not just an innocent scientific miscalculation; it was a case where powerful interests promoted weak or biased science that shaped public policy and kept dangerous products in everyday use. The eventual phase-out of leaded gasoline and paint has been linked to remarkable public health gains, but only after decades of preventable damage.

Financial Crashes and Flawed Mathematical Models

Modern finance leans heavily on complex mathematical models to assess risk, price assets, and manage massive portfolios. Before the global financial crisis of 2007–2008, many of these models treated rare disasters as so unlikely they could almost be ignored. They also often assumed that different markets and assets behaved independently of each other, when in reality panic ties everything together. These assumptions were presented with the reassuring authority of science, but they turned out to be dangerously wrong.

When housing prices fell and complex financial products began to unravel, the models failed spectacularly. Risks that had been labeled manageable or practically impossible suddenly became very real, wiping out savings, crashing banks, and triggering recessions around the world. In hindsight, the science of financial risk was not as solid as people wanted to believe. Elegant equations created an illusion of control, and their errors steered decisions at the highest levels of business and government. The crash reminds us that whenever science claims to predict the future with too much certainty – especially in complicated human systems – we should be suspicious.

Across these events, a pattern emerges: science is powerful, but never infallible, and when its errors are amplified by politics, profit, or pride, entire societies can feel the impact. The real challenge is not to expect perfection, but to stay honest about uncertainty, to question overconfidence, and to remember that today’s “settled truth” might one day be filed under the history of mistakes. Which of these stories changed the way you think about how much we should trust what we call knowledge?