The line between extinction and return is no longer a hard stop – it’s a pause button scientists are learning to unpress. Powered by ancient DNA, CRISPR editing, and a burst of conservation ambition, de-extinction has shifted from sci‑fi to lab bench reality. The pitch is dramatic: rebuild lost keystone species to repair ecosystems and future‑proof biodiversity. The caveat is just as gripping: biology is messy, ethics are thorny, and habitats have changed while we weren’t looking. Here are ten headline species at the center of this bold experiment – and what it would actually take to see them step, swim, or fly again.

Woolly Mammoth: The Ice Age Engineer

Imagine herds reshaping frozen tundra as if the last ice never melted – this is the mammoth dream in a sentence. Researchers aim to edit cold‑climate traits, like shaggy hair and fat metabolism, into Asian elephant genomes using fragments of ancient DNA. The goal isn’t a clone of a long‑gone giant but an elephant engineered to thrive in Arctic grasslands. Supporters argue such animals could compact snow, knock down shrubs, and favor grasses, potentially influencing permafrost dynamics. Critics counter that the Arctic today isn’t the Mammoth Steppe of old and that welfare, disease, and logistics loom large.

I remember touching a mammoth tooth in a museum storage room and feeling the weight of time in my palm. That same gravity now rests on labs planning surrogacy and calf rearing far from the steppe. Even if calves arrive, scaling from a few animals to functioning herds would take decades. And any release would demand Indigenous partnerships, biosecurity plans, and long‑term funding, not just one big reveal.

Passenger Pigeon: The Sky‑Darkening Forester

Once so abundant that flocks reportedly blotted out daylight, passenger pigeons shaped eastern North American forests through sheer numbers. De‑extinction efforts focus on editing band‑tailed pigeons to recapture lost traits tied to diet, breeding, and migration. The science is tricky because complex behaviors may be rooted in social learning as much as genetics. Recreating the ecological effect of billions with thousands is a massive stretch. Still, even a proxy might help restore patchy, disturbance‑driven forest mosaics.

There’s a human story here too: the species vanished within a human lifetime, a cautionary tale of unregulated harvest. Any comeback would require carefully managed flocks, predator awareness training, and disease screening. Forest managers could pair releases with habitat work that mimics historic disturbance. If you’ve ever watched a murmuration, you know the feeling – now scale that to a continent and you see the hope.

Thylacine (Tasmanian Tiger): The Silent Marsupial Predator

The thylacine sits at the emotional center of de‑extinction: a striped phantom caught forever in grainy footage. Teams are piecing together its genome and testing marsupial development using close relatives to navigate unique reproductive biology. A living thylacine‑like marsupial could help fill a mid‑sized predator niche in Tasmania’s altered ecosystems. Yet any release would collide with livestock concerns, disease risks, and the reality that prey communities have shifted since the 1930s. Rewilding isn’t just opening a gate; it’s renegotiating a social contract.

I’ve walked the thylacine gallery in Hobart and felt that mix of awe and grief that only extinction can summon. That feeling fuels funding and public interest, but it can’t substitute for hard field trials. Without suitable prey base and strong biosecurity, a comeback could falter. Success would look like careful, fenced pilots and decades of monitoring, not a dramatic reappearance in the wild.

Dodo: The Island Gardener of Mauritius

The dodo’s round silhouette hides a story about islands, vulnerability, and cascading ecological loss. Scientists are reconstructing its genome from museum specimens while mapping what kind of habitats could sustain a proxy bird. Restoring seed dispersal roles for native trees is a tempting prize, but introduced predators and habitat loss complicate everything. Conservationists would need predator‑free sanctuaries and a plan to scale biosecurity across islands. The science may be the easy part compared with the geography of safety.

Island reintroductions often hinge on small details like nest height, fruiting seasons, and storm refuges. A dodo‑like bird would need learned behaviors to avoid modern threats. And any release must support, not sideline, ongoing work for endemic reptiles and birds. The moral weight of a symbol can help raise money, but the measure of success is a stable, breeding population.

Heath Hen: The Prairie Drumbeat Lost to Silence

Once booming across the Northeast, the heath hen vanished after a last stand on Martha’s Vineyard. De‑extinction efforts target its close relatives in the prairie‑chicken clan to rebuild genotype and phenotype. The ecological pitch is clear: restore a fire‑friendly grassland bird that can shape insect communities and seed dynamics. But suburban sprawl, woody encroachment, and changing fire regimes mean the stage has changed. Habitat restoration might need to come first, not last.

Grassland birds are collapsing across much of North America, which makes a heath hen proxy both hopeful and fraught. You can’t revive a drummer without a dance floor. Agencies would need coordinated burns, grazing plans, and predator management before any eggs hatch. That’s ambitious, but it’s also the kind of practical work that leaves landscapes better either way.

Gastric‑Brooding Frog: The Amphibian That Rewrote Motherhood

These Australian frogs famously turned their stomachs into nurseries – a biological plot twist that still stuns researchers. Decades after extinction, teams briefly reactivated early‑stage embryos using preserved cells, proving a point about possibility. Beyond de‑extinction, the species offers clues to stomach acid suppression and mucosal immunity with biomedical echoes. Any return would require disease‑free, climate‑resilient habitats in a chytrid‑challenged world. Amphibians are the frontline of the biodiversity crisis, and this one could be a rallying banner.

Think of it as a moonshot for frogs: part inspiration, part method development. Captive assurance colonies, pathogen screening, and water quality safeguards would be non‑negotiable. Even if a self‑sustaining population proved elusive, the techniques could save other species. Sometimes the value is not only the animal but the toolkit it forces us to build.

Pyrenean Ibex (Bucardo): A Brief Return That Changed Everything

In 2003, scientists cloned the last Pyrenean ibex from frozen cells; the newborn lived only minutes, but a door opened. That attempt spotlighted the challenges of gestation, neonatal health, and mitochondrial mismatch. Today, improved cryobiology and embryo transfer methods make a second act conceivable. A restored high‑mountain browser could influence shrub dynamics and alpine plant communities. Yet hybridization risks and protected‑area capacity must be weighed against romantic impulses.

Standing on a ridge in the Pyrenees, you can picture a silhouette against the snowline and feel why people try. But feeling cannot replace veterinary readiness and habitat modeling. Successful reintroduction would need phased releases and genetic diversity plans. One calf is a headline; a population is a lifetime commitment.

Quagga: The Ghost Stripe of the Karoo

The quagga, a plains zebra with a sepia front and plain back, was long treated as a separate species; modern genetics nests it within plains zebras. That insight spurred selective breeding to recover quagga‑like coat patterns and, hopefully, ecological function. Even if perfect genetics remain out of reach, phenotype‑focused herds can still shape grasslands through grazing. The debate is whether a look‑alike counts when ecosystems care more about function than pedigree. In practice, vegetation response and animal welfare should drive the scorecard.

Field trials can track grass height, species composition, and soil compaction under reconstructed herds. If outcomes mirror historical grazing, the project earns its keep. If not, managers can pivot without the baggage of a single‑species narrative. That flexibility is a quiet strength of phenotype‑first de‑extinction.

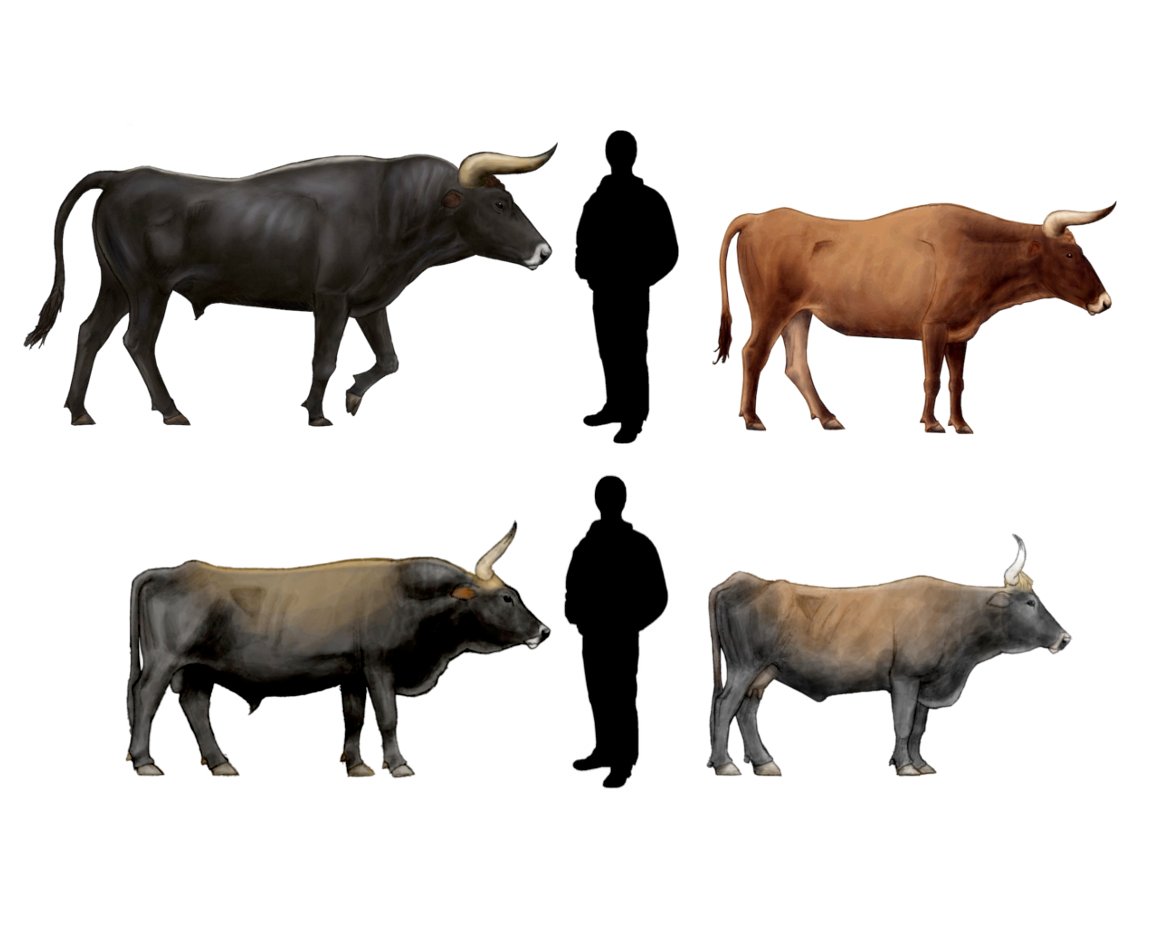

Aurochs: Europe’s Wild Cattle, Reimagined

As the ancestor of domestic cattle, the aurochs anchored Europe’s wood‑pasture landscapes for millennia. Breeding programs aim to assemble cattle lines with aurochs‑like traits – tall, robust frames; hardy behavior; and diverse diets. The hope is a self‑willed grazer that can maintain open habitats, curb shrub encroachment, and boost biodiversity. Genetics can guide, but behavior under real weather and predation pressure will write the verdict. Rewilding corridors and human‑wildlife coexistence policies are the true gatekeepers.

I’ve watched cattle in rewilded valleys change a meadow in a single season. Scale that up, and you glimpse what a near‑aurochs herd could do for butterflies, birds, and flowers. Still, fencing, disease rules, and public access need careful planning. Europe’s cultural landscapes are living mosaics, not empty canvases.

Moa: The Giant Herbivore That Left a Void

New Zealand’s moa were megafauna without the megatooth – giant browsers shaped by a world without mammalian carnivores. DNA mines from bones and eggshells have refined their family tree and opened talk of de‑extinction. But introduced predators, fragmented forests, and climate pressures make any return a high bar. Even a partial proxy could help test how lost browsing shaped forest height, fruiting, and understory paths. It’s a tantalizing ecological experiment wrapped in national identity.

Any attempt would require predator‑free sanctuaries on islands or fenced mainland zones. Browsing pressure would need careful calibration to avoid overgrazing. Cultural leadership from Māori communities is essential for design and guardianship. If it happens, it will be because science listened as much as it engineered.

Why It Matters

De‑extinction is less about nostalgia and more about leverage. By targeting species that once engineered ecosystems – grazers, dispersers, predators – scientists hope to amplify restoration with living tools. Compared with traditional reintroductions, proxies can add traits vanished from the gene pool, like cold tolerance or unique behaviors. The counterargument is straightforward: protecting what remains is cheaper and surer than remaking the lost. The honest answer is that we need both – triage today, moonshots that future‑proof tomorrow.

Here’s the pragmatic lens I use when weighing a project: does it restore function, build methods that save extant species, and strengthen local stewardship? If the plan can’t clear those bars, it’s not ready. If it can, the payoff could cascade far beyond a single animal.

The Future Landscape

Technologies are converging fast: high‑fidelity ancient DNA assembly, multiplex gene editing, embryo culture, and synthetic surrogates. On the ground, pilot sites with predator control, veterinary capacity, and long‑term monitoring are becoming the real bottlenecks. Policy is catching up with questions about liability, welfare, and cross‑border movement of engineered wildlife. Globally, climate shifts mean release sites must be modeled for decades ahead, not just today’s conditions. Equity matters too, because the communities who host these animals should shape the benefits and the rules.

Expect the next wave of progress to look incremental, not explosive – first viable embryos, then small founder groups, then cautious field trials. The headline will be a calf or chick; the story will be the network that keeps it alive.

Conclusion

If this future intrigues you, start close to home: support groups protecting habitats that would host any revival. Ask projects to publish clear welfare standards, release criteria, and long‑term funding plans, and reward the ones that do. Back biobanks and museum collections – the frozen libraries that make careful de‑extinction possible. Get involved in local burns, invasive control, or community science that restores function today. Most of all, keep the bar high: if we’re going to borrow from the past, let’s repay the future with results that last – what would you bring back, and why?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.