Long before computer models and laser-guided cranes, human beings carved mountains, moved million‑pound stones, and re‑routed rivers with nothing more than hand tools, mathematics, and sheer persistence. For a long time, these ancient engineering feats were dismissed as primitive or mysterious, as if they must have relied on lost knowledge or even myth. But new research paints a more interesting picture: these were systematic, well‑planned projects driven by clever design choices, tight logistics, and a deep understanding of materials and landscapes. As archaeologists, engineers, and materials scientists revisit old ruins with new tools, they are uncovering not only how these marvels were built, but why their underlying ideas still matter for the technologies we are working on today.

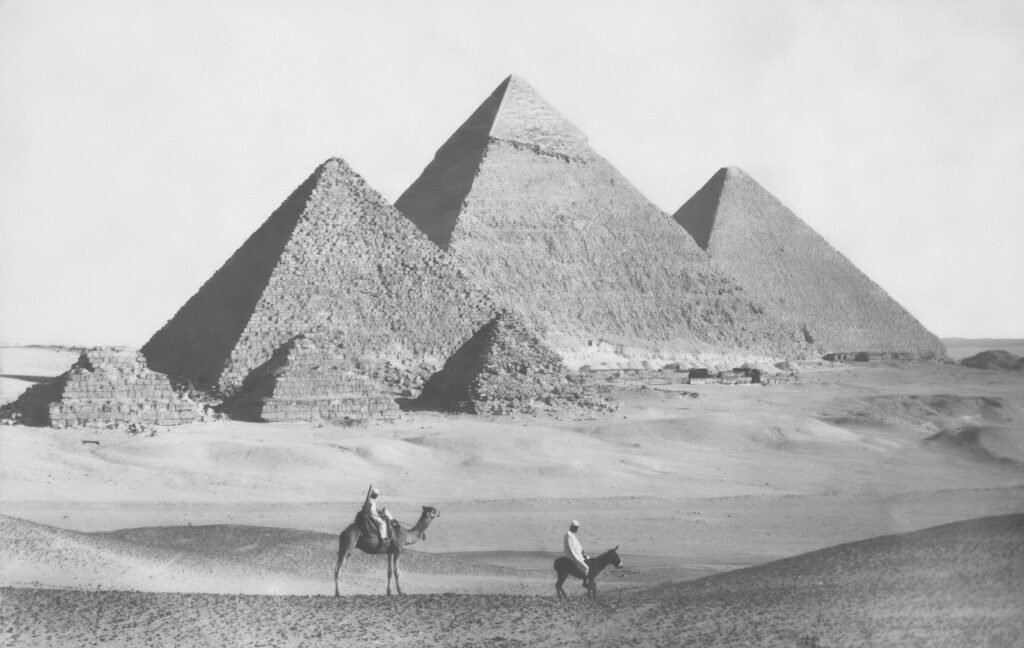

The Great Pyramid of Giza: Precision in Stone

Standing on the Giza plateau, the Great Pyramid is so familiar that it is easy to forget how astonishing it really is. Built more than four thousand years ago, it originally rose with smooth white limestone casing, aligned almost perfectly to the cardinal directions, with errors smaller than what many modern construction projects would tolerate. Engineers today point out that for a structure made from millions of stone blocks, the level of accumulated accuracy is hard to achieve without careful surveying, standardized blocks, and a tightly managed workforce. Rather than magic or mystery, the pyramid reflects a culture that treated measurement and planning as serious technologies in their own right.

Recent analyses suggest the builders may have used a combination of water‑leveling trenches, simple sighting tools, and repeated geometric checks to keep the base level and the orientation true. The logistics of quarrying, transporting, and stacking so many blocks likely relied on ramp systems that were adapted to changing stages of construction, plus bureaucratic systems to feed, house, and coordinate thousands of workers over decades. When civil engineers model the pyramid’s weight and stability, they find that its broad, tapering form is perfectly suited to withstand time, earthquakes, and desert winds. In a quiet way, the Great Pyramid functions like a stone textbook on how to design for durability rather than speed.

Roman Aqueducts: Gravity‑Powered Infrastructure

Roman aqueducts look deceptively simple from a distance, with their long chains of arches striding across valleys and hills. Up close, they reveal a fine‑tuned command of topography and hydraulics, using gentle slopes to carry water over tens of miles without pumps or modern machinery. Surveyors had to maintain a fall often no steeper than a few meters per kilometer, or the flow would erode channels or stall entirely, so they corrected course constantly with tunnels, inverted siphons, and bridges. In effect, they built a continent‑spanning water grid using gravity as the only power source.

What impresses modern engineers is not just the elegance of the concept but its resilience. Segments of some aqueducts operated for centuries, surviving political upheaval, earthquakes, and changing settlement patterns. The Romans experimented with waterproofing mortars, sedimentation basins, and control gates that allowed them to distribute water among baths, fountains, households, and farms. Today, when cities wrestle with failing pipes and water scarcity, the Roman approach – designing whole systems that anticipate wear, contamination, and growth – feels surprisingly current. Their aqueducts show that infrastructure can be both monumental and quietly practical at the same time.

Stonehenge and Megalithic Alignments: Astronomy in Architecture

Walk among the stones of Stonehenge on a misty morning and it is hard not to feel that something intentional is happening with the sky. The monument, built and modified over many centuries, aligns with the sunrise at the summer solstice and the sunset at the winter solstice, among other celestial events. Similar alignments appear at megalithic sites across Europe and beyond, where stone circles, passage graves, and standing rows frame the movements of the sun, moon, and stars. These are not accidental patterns; they imply repeated observation, data‑gathering, and experimentation woven into ritual and daily life.

From an engineering standpoint, it is the combination of astronomy and logistics that stands out. Transporting multi‑ton stones over long distances, then raising them into place with earth ramps, levers, and wooden frameworks, required organized labor and practical know‑how. At the same time, the builders were encoding sky cycles into layouts that could outlast any single generation, creating giant calendars and observatories in stone. In a sense, these structures functioned like early scientific instruments, turning the landscape itself into a device for tracking time and seasons. They remind us that engineering does not always mean machines; sometimes it is about building stable frameworks for knowledge.

The Roman Pantheon: Mastering the Concrete Dome

Step inside the Pantheon in Rome and the space nearly takes your breath away: a vast concrete dome, still the largest unreinforced one on Earth, resting on walls that have stood since antiquity. At the center, the circular opening known as the oculus pours down a moving shaft of light that doubles as both spiritual symbol and structural relief, removing heavy material from the most stressed part of the dome. What makes this even more remarkable is that Roman engineers made it all work with no steel reinforcement, relying instead on clever control of shape, thickness, and material density. They used heavier concrete mixes near the base and lighter, pumice‑rich ones near the top, effectively grading the structure to manage weight and stress.

Materials scientists studying ancient concrete have found that Roman mixes continue to harden over time as minerals grow within microscopic cracks, giving the Pantheon and similar structures an almost self‑healing character. Modern concrete, in contrast, is optimized for speed and cost rather than centuries of durability, which is one reason so many twentieth‑century buildings are already crumbling. The Pantheon’s coffering – the sunken rectangular panels cut into the inner dome – further reduces weight without sacrificing strength, a trick still used in aerospace and bridge engineering. Standing in that echoing interior, you can feel how a single building can bridge art, mathematics, and materials science, all in one bold curve of stone and mortar.

The Nazca Lines and Geo‑Scale Design: Drawing on the Desert

High above the Peruvian desert, the Nazca Lines unfold as giant geoglyphs: animals, plants, and perfectly straight lines stretching for kilometers, drawn by removing dark surface stones to reveal lighter soil beneath. From ground level, many of the figures are almost impossible to grasp, yet their proportions and geometry are strikingly consistent. To create them, the Nazca people did not have aircraft or satellites, but they did have systematic methods: simple sighting posts, rope grids, and iterative corrections that allowed a design sketched on a small scale to be translated into the landscape. This is large‑format engineering as much as large‑format art.

What captivates researchers is how such projects encode planning and collaboration across communities. Maintaining vast open lines on a windy, shifting desert floor likely required ongoing upkeep and shared rules about land use. The precision of long straight segments suggests repeated surveying and an intuitive grasp of how to project lines over uneven terrain. Today’s cartographers and remote‑sensing scientists use satellite imagery and drones to map the lines in higher detail than ever before, but the basic challenge – coordinating vision and execution over big distances – is the same. The Nazca Lines remind us that humans were managing geospatial projects long before we gave them technical names.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science: What These Marvels Reveal

When modern engineers reverse‑engineer these ancient projects, one theme keeps appearing: sophisticated outcomes do not always require sophisticated tools. The Egyptians, Romans, and Nazca designers worked with materials at hand – stone, wood, ropes, water, and earth – but pushed them with relentless iteration. Instead of computer simulations, they relied on scaled models, rule‑of‑thumb calculations, and centuries of accumulated craft knowledge passed from one generation of builders to the next. In practice, that meant using repeatable processes, templates, and quality checks that would look familiar on a twenty‑first‑century construction site.

Comparisons with modern methods are especially revealing. Today, we lean heavily on digital design and heavy machinery, which allows for rapid innovation but can also isolate designers from the tactile realities of structure and stress. Ancient engineers, by contrast, experienced feedback in real time: a crane broke, a stone cracked, an arch buckled, and they adjusted their methods. Their test rigs were the landscapes themselves. In a way, this grounded approach fostered a culture of conservative but reliable design, where failure was expensive enough to make long‑term thinking non‑negotiable.

Why It Matters: Rethinking Progress and Sustainability

It is tempting to view these ancient feats as curiosities from a distant past, but they quietly challenge some of our assumptions about progress. Many of the structures that dominate the archaeological record were not just impressive when they were built; they were designed to last through generations, sometimes millennia. In an age where buildings may be replaced within a few decades, the idea of constructing something meant to outlive political cycles and economic trends feels almost radical. These monuments also force us to confront the environmental costs baked into our own infrastructure choices.

Consider how Roman concrete, with its lower‑temperature production and self‑healing chemistry, offers hints toward more sustainable building materials. Or how gravity‑driven aqueducts inspire renewed interest in low‑energy water systems that could help regions facing climate‑amplified drought. Ancient designs were not environmentally perfect, and some demanded enormous human and ecological sacrifice, but they often worked with natural forces rather than against them. For modern society, grappling with the climate crisis and resource limits, the most important lesson may be that resilience and elegance can go hand in hand. These old stones quietly ask whether we are thinking far enough ahead.

Global Perspectives: Shared Patterns Across Civilizations

What strikes me, looking across continents and centuries, is how different cultures converged on similar engineering instincts. Whether it was the step pyramids of Mesoamerica, the rock‑cut temples of India, or desert cities that harvested rare rains through underground channels, people confronted the same problems: how to store water, manage weight, resist earthquakes, and mark sacred time. In many cases, they solved them using patterns we still recognize, like buttressed walls, modular bricks, or redundant supports that prevent cascades of failure. These recurring motifs hint at an informal, global laboratory of trial and error that spanned the ancient world.

At the same time, each region adapted solutions to its specific geology, climate, and social structure. Mountain societies learned to anchor terraces into slopes; coastal ones experimented with wave‑resistant harbors. Engineers today talk about context‑sensitive design as if it were a modern insight, yet ancient builders practiced it as a matter of survival. This shared but locally tuned heritage is a reminder that innovation does not belong to any single culture or era. Instead, it emerges wherever people push against the limits of their surroundings with patience and imagination.

The Future Landscape: Learning Forward From Ancient Technologies

Looking ahead, researchers are increasingly treating ancient engineering not as a dead chapter, but as a living sourcebook for new ideas. Materials scientists are probing Roman concrete recipes to design low‑carbon, self‑healing materials for sea walls, bridges, and coastal cities threatened by rising oceans. Hydrologists study traditional canal systems and stepwells to rethink urban water storage in regions facing erratic rainfall. Even architects are revisiting passive cooling tricks from desert structures – thick walls, shaded courtyards, wind towers – to reduce dependence on energy‑hungry air conditioning.

This is not nostalgia; it is a pragmatic search for techniques that have already been field‑tested over centuries. The challenge is to mesh these older insights with modern constraints such as dense populations, complex supply chains, and rapidly changing climates. In practice, that might mean blending advanced modeling with vernacular forms, or pairing high‑tech sensors with low‑tech materials. The risk is that we cherry‑pick aesthetics while ignoring the careful systems thinking that made ancient marvels work. The opportunity is to build a future where skyscrapers, dams, and data centers are judged not only by their performance on day one, but by their ability to age as gracefully as a Roman dome.

How You Can Engage With Ancient Engineering Today

You do not need to be an archaeologist or engineer to take something practical from these old structures. Visiting ancient sites – even virtually through detailed 3D tours – can shift how you think about scale, time, and what counts as advanced technology. Supporting museums, heritage organizations, and local guides helps fund the careful documentation and conservation that keep these places from quietly eroding away. Many research projects now share open data, models, and reconstructions online, inviting curious outsiders to explore, question, and even contribute.

On a more everyday level, paying attention to the built environment around you – bridges, public buildings, water systems – can be a first step toward asking better questions about how and why we build. When a city debates demolishing an old structure or investing in more robust materials, public pressure can nudge decisions toward long‑term thinking. You can look for citizen‑science initiatives that map heritage sites, monitor damage, or document traditional building techniques before they vanish. In a world that moves fast, choosing to value and protect slow, durable engineering is its own kind of quiet activism.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.