They build underground cities without blueprints, farm food they can’t live without, and patrol crops like tireless bodyguards. For decades, ants were cast as picnic thieves and kitchen invaders, yet the real story is far wilder and far more useful to us. Scientists now read ant societies as living laboratories for agriculture, engineering, and sustainable pest control. The mystery is how such tiny bodies pull off feats that rival our own systems, and the twist is this: their solutions are often simpler, cleaner, and more durable than ours.

The Hidden Clues

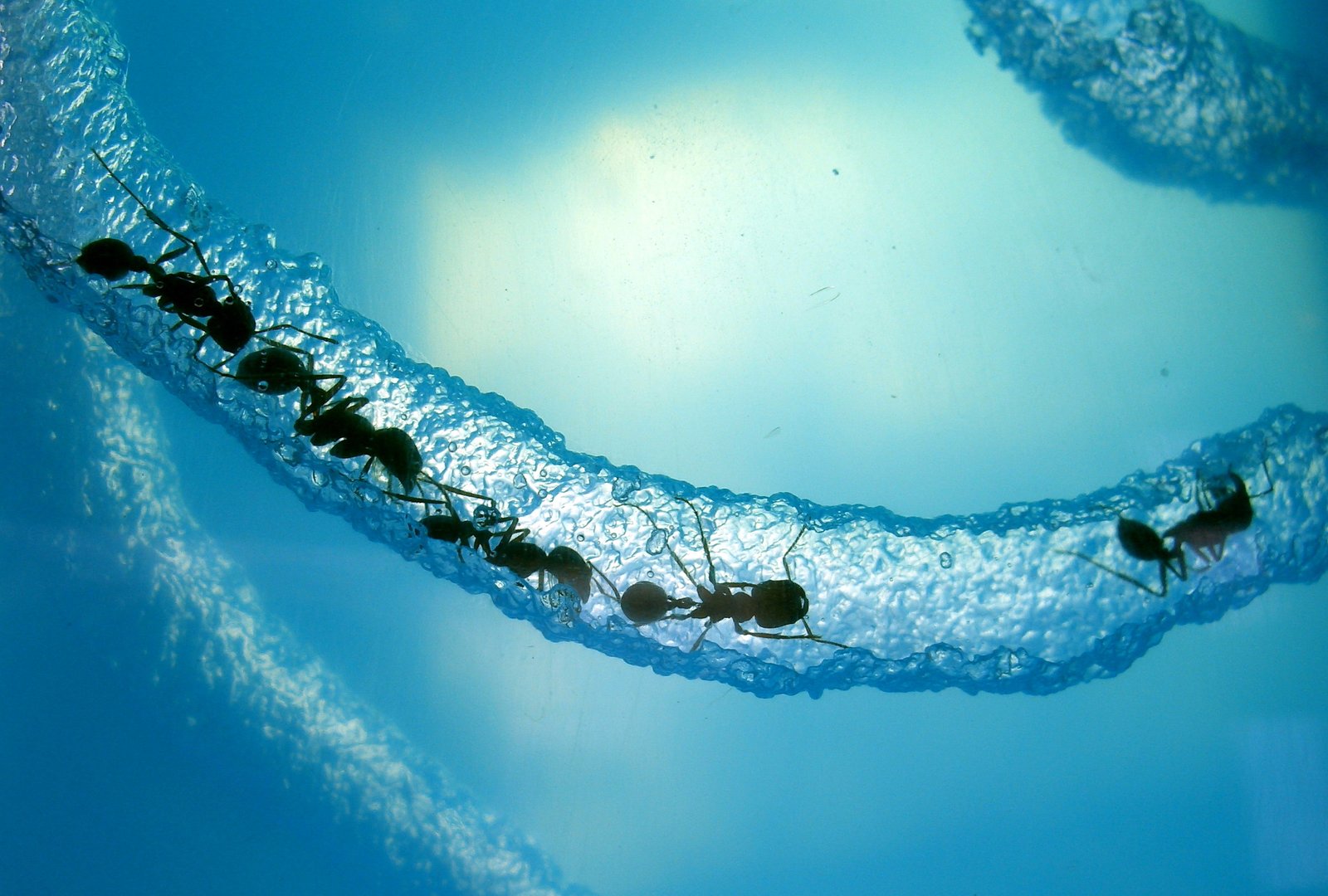

Walk across a lawn and you might be stepping over tens of thousands of decisions per hour – where to dig, what to harvest, which path to patrol – coordinated by brainlets the size of sesame seeds. Ants are not just abundant; their global presence shapes soils, seeds, and food chains in quiet but decisive ways. Researchers now estimate the world holds a staggering number of ants, on the order of the tens of quadrillions, which helps explain why their collective impact is felt almost everywhere.

These hidden lives matter because the behaviors we glimpse at the surface – tidy soil mounds, marching trails, bits of leaf on the move – are the tips of deep, evolving systems. Ants manage resources, maintain infrastructure, and enforce colony health with a ruthlessly practical logic that often outperforms ours. When we read the clues properly, ants become tutors in efficiency, resilience, and restraint.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Long before humans domesticated wheat, leafcutter ants in the Americas domesticated a fungus and never looked back. Atta and Acromyrmex colonies gather fresh vegetation not to eat directly but to feed a specialized crop – a fungal partner that converts leaves into a rich, edible matrix for the colony. This agricultural pact emerged tens of millions of years ago and has been refined with remarkable precision.

Modern science is catching up to that sophistication. Imaging technologies have revealed labyrinthine gardens and waste chambers with traffic lanes as efficient as urban transit. Microbiology adds another twist: many farming ants carry helpful bacteria on their bodies that produce natural antibiotics, protecting their crops from fungal parasites with chemistry that rivals our own pharmacies.

Underground Cities

Beneath a quiet patch of ground, a mature colony can run a city’s worth of logistics. Deep chambers house the queen and brood, mid-level rooms cycle air and moisture, and surface tunnels open and close depending on wind, temperature, and the day’s workload. The architecture is not random; it’s engineered by thousands of tiny actions, like grains of sand nudged just so, hour after hour.

Ventilation is a masterpiece of low-tech design. Some species create shafts that catch breezes, pushing fresh air down while warmer, carbon-dioxide-rich air escapes elsewhere. Waste is quarantined in dedicated dumps far from nurseries and food storage, lowering disease risk with a spatial hygiene plan any hospital would admire. No concrete, no pumps – just physics and patience.

Tiny Farmers With Giant Yields

Fungus-farming ants are meticulous growers. Workers clean leaves, mulch them to the right texture, seed the material with fungal starter, and weed out invaders. Specialized “gardeners” tend the crop day and night, pruning and reseeding as conditions shift. The payoff is reliable, protein-rich food that can sustain supercolonies for years.

Other ants run smaller side hustles. Some herd aphids and scale insects for sugary honeydew, corralling them to safer plant spots like shepherds moving flocks. A few species even reorganize their herds when predators show up, an adaptive pastoralism that boosts colony calories without burning extra energy. It’s agriculture scaled to the gram, but potent at the landscape level.

Pest Control, Ant-Style

In orchards from Southeast Asia to Africa, weaver ants are valued allies, patrolling tree canopies and attacking leaf-chewing pests with coordinated strikes. Farmers have used them for centuries, and recent field trials show they can reduce pest damage and help maintain yields while cutting down on chemical sprays. Ant patrols are not a silver bullet, but they can be a sharp tool in an integrated toolkit.

On coffee and cacao, native ant guilds often suppress borers and defoliators simply by being present in healthy numbers. The strategy works best when farms retain shade trees, floral resources, and nesting sites that keep ant communities robust. In a warming, pesticide-fatigued world, that sort of biological insurance is increasingly valuable.

Why It Matters

We spend fortunes battling pests, aerating soils, and managing waste – but ants have built-in solutions that run on sunlight, teamwork, and feedback loops. Compared with conventional pesticide regimes, ant-based control can lower chemical inputs, reduce resistance risks, and support beneficial insects that keep systems stable. In regions where smallholder farmers face narrow margins, those savings and safeguards can be the difference between surviving a bad season and losing the farm.

Ants also boost the living architecture of ecosystems. By tunneling, they aerate soils and move nutrients; by carrying seeds, they help plants spread and regenerate after disturbance. That means healthier forests, more resilient croplands, and landscapes that soak up water and carbon more effectively. Investing in the conditions ants need often pays back as broader ecosystem services we all rely on.

Global Perspectives

Ant benefits aren’t distributed evenly, and context matters. Invasive species like the Argentine ant can bulldoze native food webs, disrupt pollination, and even undercut natural pest control by displacing helpful natives. In those cases, precision management – baited lures, habitat tweaks, and quarantine of high-risk pathways – becomes essential.

Cultural knowledge already points the way. Orchard keepers in the tropics have centuries of know-how on harnessing canopy ants, while conservationists in temperate regions are learning how leaf litter, dead wood, and native ground cover recruit pest-eating ant communities. The common denominator is habitat: give ants the architecture they need, and they tend to return the favor.

The Future Landscape

New tools are poised to make ant-powered agriculture smarter and more predictable. Lightweight sensors and computer vision can map patrol routes and hotspots of pest pressure, turning “watch the ants” into actionable dashboards for growers. Environmental DNA from soil and leaf wash can flag which ant species are present and whether the community is shifting in helpful or harmful ways.

There’s also a feedback from biology to engineering. Swarm robotics and routing algorithms borrow ant logic to move drones through orchards, target trouble spots, and schedule interventions only when needed. Add safer, species-specific baits for invasive ants and better guidelines for integrating ant allies with minimal chemical use, and the near-future farm looks both high-tech and more alive.

Conclusion

If you grow food – on a balcony, in a backyard, or across a hillside – start by protecting the small habitats ants need: leaf litter, living ground cover, and pesticide-free refuges. Try simple monitoring: note which ants show up, when they patrol, and what pests they attack, then adjust mulching, pruning, and flowering strips to support the helpful crews. For invasive ants, act early with local extension advice and targeted methods that avoid collateral damage to native species.

Support research and community science that track ant diversity across farms and cities, because data lights the path to smarter management. Encourage schools and community gardens to make ant-watch a learning tool, and push for policies that reward reduced chemical inputs where biological control is working. Small changes on the ground, multiplied by millions of tiny workers, add up fast.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.